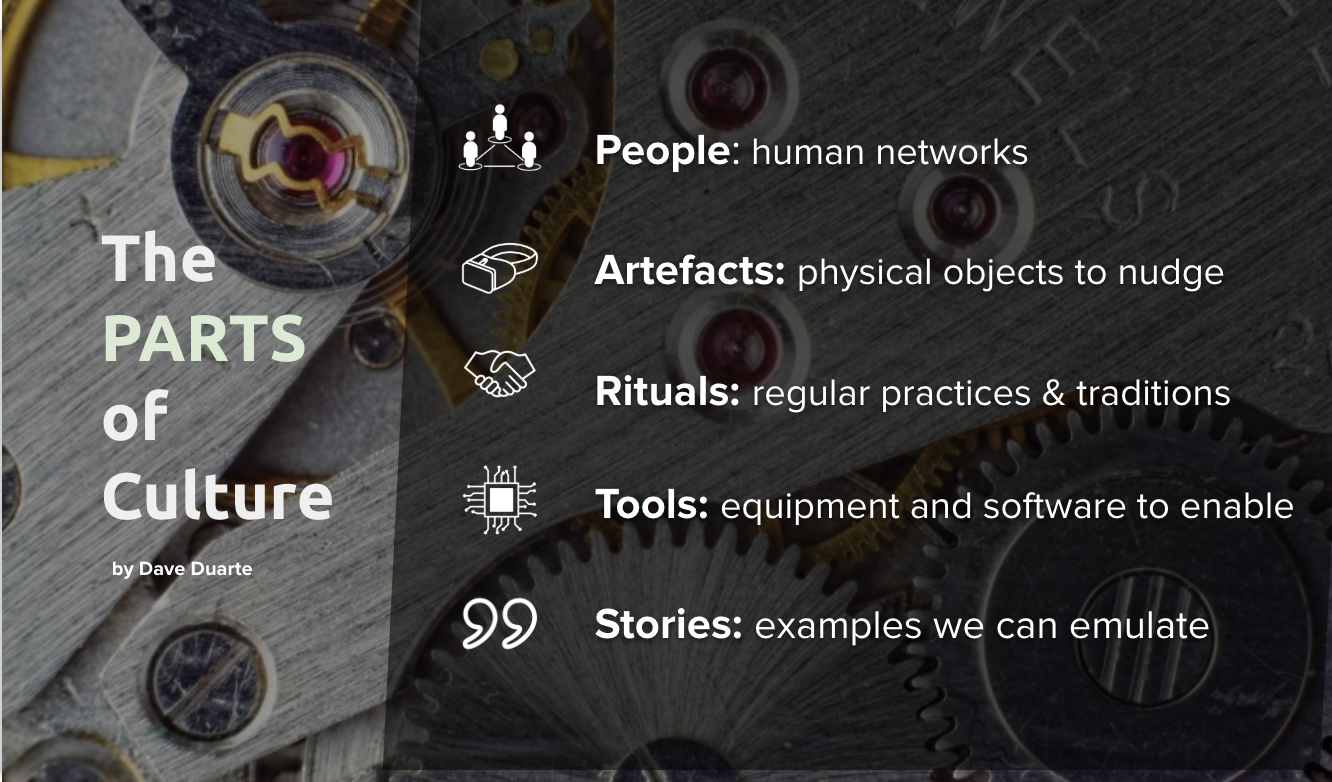

PARTS: The 5 working parts of company culture

Every good leader knows the importance of Company Culture, and yet it is difficult to grasp and actively shape. Culture determines a groups capability to respond to change, and to function as more than the sum of its parts. To help get a handle on this seemingly intangible concept let us introduce you to the PARTS of culture.

By Dave Duarte

Culture is the hidden force that shapes our decision-making day to day, what we value, and how we get things done. And yet culture isn’t something that can be set in place, it is emergent and adapts.

The PARTS of Culture provides an memorable framework to work with when aiming to influence culture. It stands for People, Artefacts, Rituals, Tools, and Stories.

A bit of background

When we launched the OgilvyDMA in 2010, Rob Hill and Gavin Levinsohn said our primary objective was to help "geekify" the Ogilvy Cape Town culture. Now, "Changing Culture" sounds all well and good, but when it came to it I had no idea where to start. I turned to sociological theory on culture for clarity, and out of that developed PARTS as a way to make the key concepts memorable and strategically actionable.

Here’s more details on each of these aspects, and how we applied them with remarkable success at Ogilvy.

People: gain the support of a few well connected people, and help them recruit others

Too many companies make the mistake of trying to change the whole company at once. You’re more likely to gain traction incubating culture among a group of influential people who have provide reach and access to the rest of the organisation.

Behaviours spread from person to person (Christakis, 2007). So it's important to work with a small group of people initially to make sure the cultural change is understood and adapted.

The key players in a social network are your Experts, Influencers, Gatekeepers, and Connectors. Each are important in their own ways, and you need to gain their support for any culture change initiative. These people need to have a high frequency of contact with the cultural change process an practice. They are going to be the ones that set the example and distribute the culture to the rest of the organisation. As Derek Sivers famously put it "new followers don't follow the leader, they follow the other followers."

At Ogilvy, the most influential people throughout the agency were invited to our first Ogilvy Digital Marketing Academy, and no expense was spared in ensuring a transformative learning experience that created group buy-in and connection.

Artefacts: make the culture change public and visible

Our physical environment and the objects in it form the stage on which your staff perform. Are you setting them up for great performances, giving them the cues and props they need? Art, Awards, and artefacts of belonging (like lapel pins, t-shirts, certificates) all serve to communicate cultural values.

Open Knowledge Foundation, "OPEN" lapel pin, by Brian Glanz

Amazon, for example, reminds people of their value of frugality through the use of door-desks throughout the company.

Ogilvy encouraged more a more digitally savvy culture by making the latest gadgets available to staff through Ogilvy Labs. There are screens live-streaming social data from clients, there are interactive demos of the latest in sensory technology around the office, and there are framed certificates displayed for people who complete digital training. Other artefacts could include the kinds of awards that are valued, for example, displaying Cannes Lions, or Bookmark Awards.

Rituals: Go from a moment to a movement

The things a company does regularly become a signal of their culture. The rituals can be small or large, everything from how you on-board staff to how you handle daily meetings.

The key thing when you want to introduce a ritual is to do it consistently and repeatedly. It takes time for new behaviours to take root. Your company values aren’t just things that you just write down and forget about, they should be reflected in what behaviours you reward. In who you hire, promote and let go. These create behavioural norms that become embedded in your company culture.

For example, Ogilvy hosts a regular “How-To Friday” session where people who have done something extraordinary share how they did it. This signals the company’s long-term commitment to hands-on innovation.

Tools: give people the resources to create change

How do you equip your people to do their work in a way that reflects company culture? You can't expect change if you don't enable it. Language, skills, technology, equipment, and other resources are major enablers of change.

The most fundamental tool for culture-shaping is language. When you want to shift culture, equip people with new ways to talk about what they do.

A key part of the Ogilvy Digital Marketing Academy's success was, and is, giving people the language to speak about digital. Concepts like Impressions, Reach, Landing Pages, and Programmatic become more useful when we have the words to talk about them.

Story: don't just tell people about the change, show them what others are doing

Stories are the way that people naturally encode and share complex social information. There are two ways a company can bring their story to life: storytelling and storymaking.

Storytelling is about finding examples of good cultural practice and crafting stories around those actions so that it is easier for others to understand what to do, and to emulate the success of the cultural heroes you celebrate.

Storymaking is about kickstarting this process. It’s not just about what you celebrate, but also how you take action. It is about taking decisive action to establish cultural precedence.

At Ogilvy, stories were created by investing more heavily in case-studies involving digital integration, such as Be The Coach (which went on to become the most awarded campaign of the year - winning international plaudits including four Gold Lions at Cannes)

Stories are like software for the mind. They help us understand cause and effect, and can have a transformative effect on what we see as possible and expected.

The results of the first application of our PARTS model can best be summed up by Ogilvy Cape Town's Managing Director, Gavin Levinson

“What’s the best thing that’s happened in the Ogilvy ‘family’ over the past three years? While there are many highlights and accolades within and across all of Ogilvy’s companies, I would undoubtably say that the ODMA has and continues to be our finest hour.”

Treeshake offers story-making workshops and talks on culture change, leading innovation, and values-driven leadership.

#BI4Gov: How a small, but deeply engaged community can have HUGE impact

How a new Twitter account with no followers and no paid media budget got a niche topic trending and reached over 2 million people in less than two weeks.

This case study is about how a new Twitter account with no followers and no paid media budget got a niche topic trending and reached over 2 million people in less than two weeks.

In late 2018, Treeshake helped launch #BI4Gov, a conference focused on how to use behavioural insights to successfully shape and implement policy, in a socially beneficial way. Through a partnership between the Western Cape Government (WCG) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), experts from throughout the world came together to discuss the ins and outs of using BI in Government.

Starting with a brand new account with no followers on Twitter, and just two weeks to launch we knew that we’d be reliant on the voices of others with larger followings.

The first step was to set up the account to look as credible as it was - partner logos, clean design, and 3 high quality posts were set up. We then sent the page around to the team of collaborators and asked them to engage with the posts and follow so we’d have a bit of traction.

The next step was to tap into BI communities on Twitter, and identify thought leaders. We directly engaged around 60 followers ahead of the conference and directly asked them to follow us and help us get the #BI4Gov discussion going. We did this by email and direct message rather than publicly.

We found the BI enthusiasts supportive, warm, and welcoming to a new entrant to the space - this is partly thanks to declaring our agenda upfront, having the backing of the OECD, and introducing ourselves directly to the main thought leaders. This got the conversation rolling, and even with a relatively small following, everything we posted got a response.

The official Twitter account quickly gained around 150 followers. Without any paid advertising budget, we relied solely on consistent, authentic engagement with each member of the community. These followers were all highly skilled BI experts, each of whom had very strong links to the overall online BI community. This allowed for a higher degree of sophistication in the commentary and posts we put out, along with a much higher than average engagement rate.

On the day of the conference, the hashtag was visibly promoted at the conference, attended by around 300 people - many of whom had been contacted by the social media team ahead of time to let them know the importance of sharing their views. The result was that virtually everyone who attended participated in the online discussion, sharing substantive content that attracted public interest and media attention.

But it wasn’t all serious, either. As participants got to know each other, playful Twitter banter emerged in the form of ‘the sock saga’, with various speakers and organisers of the event comparing their funky sock choices. With the perfect mix of serious, insightful and fun, the #BI4Gov community blew us away with their deep engagement and commitment to the conversation.

Most importantly, the conference and public support for the issue has led to the establishment of South Africa’s first Behavioural Insights Unit in Government - #BI4Gov is here to stay.

The main take away from this? A small group of deeply engaged people can make a huge impact. Inspired by Cultural Anthropologist Margaret Mead, this is something we call The Mead Principle:

Behavioural Insights in government: Nudging for change

Policy and Behavioural Science may not seem like a natural fit, but they are. Our behaviours and choices have a huge effect on the way a city works - for example, how much water we use; what public transport we take; how much electricity we use; whether we litter; and so on. Government can’t force people to behave in a particular way, it always comes down to personal choice.

This week in Cape Town, experts from around the world converge to discuss the use of Behavioural Insights in Government. A partnership between the Western Cape Government (WCG) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), discussions focus on how to apply BI to shaping and implementing policy.

Policy and Behavioural Science may not seem like a natural fit, but they are. Our behaviours and choices have a huge effect on the way a city works - for example, how much water we use; what public transport we take; how much electricity we use; whether we litter; and so on. Government can’t force people to behave in a particular way, it always comes down to personal choice.

But government can shape policy in a way that makes it easier to make choices that benefit the most people.

Behavioural Insights (BI) is gaining acceptance as one of the most effective ways for government to bring about social benefit through policy. The Policy and Strategy Unit in the Department of the Western Cape Premier has been studying and engaging with BI since 2012, and the UK government has famously had a ‘Nudge Unit’ (the Behavioural Insights Team) since 2010. But if we look at the South African context, where we’re faced with high rates of HIV infection, crime, obesity and other socio-economic issues, understanding human behaviour and how to change it from within becomes even more critical.

Since 2012, the WCG has worked with the Research Unit in Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics (RUBEN) at UCT, to create some of these solutions. RUBEN is an interdisciplinary group of researchers using economic research methods to look at how social, cognitive and emotional factors influence our economic decision-making.

One of the first projects piloted was on energy efficiency - encouraging the Western Cape Government to cut down on energy consumption. We wanted to understand why employees were leaving lights on all weekend, and nudge them to switch lights off.

We identified 6 behavioural bottlenecks that were standing in the way of energy efficient behaviour:

Diffused responsibility: employees not understanding whose responsibility it was.

Moral justification: public service employees felt they were contributing positively to the environment already.

Unit confusion: employees not understanding the significance of simply switching off a light.

Limited attention: forgetfulness played a big part in this.

Identity: when employees were in “work mode” they forgot their energy efficient behaviour from home.

Social norms: there was no reference point for personal energy consumption in relation to colleagues.

We used these insights to design an intervention that led to a 14% reduction in energy, which was deemed statistically significant. This is one of the aspects of BI that is so beneficial to policy: by measuring the results, you gain an understanding of what works - and doesn’t work - before you roll out the policy to everyone.

Behavioural Insights offers a set of tools and methodologies that we can use make a real difference in South Africa.

If you would like to keep track, or get involved, please engage using the hashtag #BI4gov on Twitter or @bi4gov.

How - and why - Behavioural Insights can help governments

The inclusion of BI into the processes of policy-making allows for governmental policy that not only accurately represents human interests, but has practical, well-researched examples and case studies. What does that mean? Everything is verified. BI’s focus is on creating and substantiating policies that prioritise human needs - and behaviours.

“There is a movement afoot to weave psychological science into the fabric of government. And by using the words ‘weave’ and ‘fabric’, I mean to signal something unique: an attempt, now emerging from within government itself, to integrate the insights and experimental methods from the psychological sciences directly into day-to-day governance.” David Yokum: Director of The Lab @ DC, Washington DC, USA.

Understanding the ‘why’ behind people’s actions - the reasons they behave the way they do and, just as interestingly, don’t behave the way they should - is the primary fascination behind Behavioural Insights (BI). As a result, BI is seeing exponential growth in its capacity as an innovative approach to policy-making. Because it is grounded in research from multiple fields such as cognitive science, social science and psychology, BI provides a deeper understanding of how humans make choices, in a way that supports human-centric policy.

The end result? Policy-making that accurately reflects and represents human interests.

Understanding BI’s role

BI is one part of a triangle: consisting of BI, BS and BE. Or, in other words, “one discipline in a family of three, the others being behavioural sciences and behavioural economics” (Lunn, 2014; OECD, 2016). In order to understand BI, it’s helpful to unpack the related disciplines that inform it:

Behavioural Sciences (BS) encompass the study of human behaviour through a scientific lens, and often intersect with the broader social sciences, such as anthropology, psychology and sociology.

Behavioural Economics (BE) examines economic decision-making from a behavioural standpoint, emphasising the psychological, cultural and social factors which influence these decisions, rather than viewing economics from a purely theoretical perspective.

The inclusion of BI into the processes of policy-making allows for governmental policy that not only accurately represents human interests, but has practical, well-researched examples and case studies. What does that mean? Everything is verified. These examples and case studies illustrate proven, real-world outcomes. BI’s focus is on creating and substantiating policies that prioritise human needs - and behaviours. Policy-making in government and public institutions has a greater chance of consistent and successful projections if it includes BI.

Guiding principles for BI in government

Since 2013, the OECD have been a significant supporter of public institutions using behavioural insights in public policy. They understand that for BI to become an invaluable policy-making tool, we need, “guiding principles and standards… to guide future applications and maintain the trust of public bodies and citizens” (OECD, 2017). Although BI has generally been used in the late design phases of policy, the potential for integration is much larger. “So far, BI has been mostly applied while implementing policies - often fixing policies that hadn’t fully reflected how individuals actually behave and make decisions,” explains Filippo Cavassini, Economic Adviser in the Regulatory Policy Division of the Public Governance Directorate at the OECD. “But thinking early about actual behaviours can make a difference in improving the effectiveness of public policies. This includes health services, how teachers and students learn, how to keep neighbourhoods safe and how to use natural resources sustainably.”

Making life better, using BI

BI has been used to improve consumer experience in multiple instances. In 2015, for instance, the OECD worked with the Columbia Communications Regulator (CCR) to address user complaints regarding expensive, unsatisfactory products and communication services. Their team did research into the issue, and experimented with ways to improve and redesign the regulatory regime to protect consumers. The results were assessed with quantitative and qualitative methods, and the proposed policy change was opened for public consultation. The result? A new, successful, behaviourally-informed consumer protection regime, which monitored user response to determine satisfaction.

Implementing BI into the policy-making of government and other public institutions allows for policy that truly reflects, represents and supports human interest in a holistic way. Using BI in this way acknowledges the validity of theoretical strategies, without diminishing the value of empirical scientific methods.

We all agree - on some level - that our governments are there to guide and help citizens to live better lives. How much more effective would these governments be if, instead of making decisions behind closed doors, they welcome the behavioural insights of the people they are trying to serve? BI in government is not new - the OECD reports that over 200 institutions within and outside government are applying behavioural insights to design and implement public policies.

The question is: why isn’t it every department in every government?

If you’re looking for even more info on what BI can do for policy-making, head over to the BI4Gov website and register for South Africa’s first Behavioural Insights conference.

13 Essential Behavioural Insights for Changemakers

Behavioural Insights (BI) offers a set of proven methods that can be used. The field combines elements of psychology, cognitive science and social science to understand how people actually make decisions. These principles of BI are fascinating and apply to all of our lives and decisions. This article provides an overview of 13 proven principles that can be used to nudge our choices and actions.

We know we should eat healthily, exercise more, recycle, stop littering, donate blood, and reduce our water use. So why don’t we just do everything right? Well, humans are not always rational, and behaviour change can be hard.

Behavioural Insights (BI) offers a set of proven methods that can be used. The field combines elements of psychology, cognitive science and social science to understand how people actually make decisions.

For policy makers in government this is especially important, because the daily choices people make in their lives - from whether to use condoms, to what public transport to use - can have massive implications when multiplied by millions of citizens. The Cape Town water crisis of 2018 is a case in point.

This is why the OECD and the Western Cape Government are organising the Behavioural Insights Conference in Cape Town on the 27th and 28th September 2018: @BI4Gov. The Conference is bringing together BI authorities from all over the world to discuss how to apply the science of human behaviour and decision-making to public policy.

These principles of BI are fascinating and apply to all of our lives and decisions. This article provides an overview of 13 proven principles that can be used to nudge our choices and actions.

13 essential Behavioural Insights terms:

1. Anchoring:

The act of anchoring thoughts or decisions on the first piece of information we receive about a topic - whether or not it’s relevant or the best information. If you’re asked to guess the price of something and have recently answered an arbitrary question with a number (such as: how old are you?), your answer is more likely to be anchored to that number. Our decisions are anchored by mental reference points, whether or not they apply.

2. Availability Heuristic:

The availability heuristic speaks to the way we make decisions based on how easily we can access information about the topic. We judge something as more likely to happen if we can easily recall an incident or example of it happening before - even though our availability is largely influenced by what the media chooses to focus on. A common example of the availability heuristic is the question: What do more people die of, shark attacks or being hit on the head with a coconut? About 80% of people say that shark attacks cause more deaths, but that’s not true. There are far more coconuts falling from trees than fatal shark attacks, yet shark attacks are usually scary and gory, so they get all the media attention. As a result, they are more available to us and we can remember them more quickly.

3. Behavioural Bias:

Behavioural Biases are a group of behaviours (including Anchoring, Commitment, Confirmation Bias, Decision Fatigue, Framing, Loss Aversion, Optimism Bias and Priming) that cause us to act in an irrational way and make bad decisions; without being aware that we’re acting because of a bias. They are also sometimes called Cognitive Biases.

4. Confirmation Bias:

Confirmation Bias is when we seek out opinions and information that confirm our existing preconceptions and thinking. It is reassuring to believe that we have made the right decisions, so even when potentially looking for alternatives, we are often motivated to find confirmation of our current choices.

5. Commitment:

We see the effect of commitment when people publicly commit themselves to something - an idea, a person, a cause - and then feel obligated to follow through. Commitment is also seen when people are involved in creating things themselves, and feel more strongly about that thing. IKEA plays strongly on this idea: people are disproportionately attached to their IKEA furniture because they had to put it together themselves. The IKEA Effect studied how much more people were willing to pay for a simple IKEA storage box when they had put it together themselves. The result? Significantly more. Commitments have been shown to be most effective when there is a great cost to breaking them, as in a penalty to pay if you withdraw an investment early.

6. Decision Fatigue:

Making decisions is an exhausting activity, and when we are required to make numerous decisions in a day, we often suffer from Decision Fatigue - which leads to making poor decisions. Studies have shown that judges are more lenient when they’ve just had a snack break or lunch, which is an example of decision fatigue.

7. Framing:

Framing speaks to the way we make decisions based on how the information is presented - how it is framed. Choices can highlight one of two sides to any product or situation: the positive or the negative. Describing a cut of meat as 95% lean is far more appealing than describing it as 5% fat. Similarly, ‘virtually sugar-free’ sounds much healthier than 7% pure sugar.

8. Heuristic:

Heuristics are a set of cognitive shortcuts that make decision-making easier. You can think of them as rules or shortcuts that help to reduce our mental load, but they aren’t always perfect. There are a number of common heuristics (like the Availability Heuristic). An example of a heuristic is substituting an easier question for a hard one. So instead of answering the question, “Should I invest in this company?” we swap it out to, “Do I like this company?”

9. Loss Aversion:

It is twice as painful to lose something as it is to gain something (even if that ‘something’ is of the same value). So we are far more motivated to avoid losses than to seek out gains. If a friend offered you a coin toss where you had to give her R100 if it landed on heads and she would give you R100 if it landed on tails, would you take that gamble? Most of us wouldn’t - we would require the winning amount to be twice as much as the amount we might lose. Losses have a larger psychological impact on us than gains.

10. Nudging:

Perhaps the most famous term in BI, nudging, refers to a subtle intervention that suggests people act in a certain way while still allowing them free will. A nudge alters our behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any specific actions. If you think about the way a GPS guides you to your destination, that’s nudging.

11. Optimism Bias:

We have a tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive things happening to us, and underestimate the likelihood of negative events happening to us - this is optimism bias. We don’t think it’s likely that we’ll get in a car accident, relative to other people. Yet the other people also don’t think it’s likely that they’ll get in a car accident.

12. Priming:

Priming refers to subconscious cues that can affect our behaviour and actions. Priming activates linked memories, associations and stereotypes that are subconscious. Studies have been done that show that simply reading words associated with old age - lonely, grey, wrinkled - (interspersed with other words so it’s not a conscious association) make us walk more slowly.

13. Social Norms:

We are heavily influenced by what the people around us are doing - by what the societal norms are. This affects both our behaviour and our decisions, and can be seen as behavioural expectations or rules within a group of people. This is often used in behaviour change by highlighting individual consumption (for example, water use) in comparison to the average in your neighbourhood or city.

Now that you’re clued up, head over to the BI4Gov website and register for South Africa’s first Behavioural Insights conference. Registration is free for approved delegates - it’s sure to be 95% interesting (and that’s not framing).

All images by Recombiner

The Taste Gap

So many of us get into social media because we admire the work of creatives in the field, the brilliant memes, the awe inspiring videos, the perspective altering tweets. But there’s a gap when we start. What we produce doesn’t live up to our own expectations. Ira Glass’ insights on the creative process remind us to push through the frustrating beginnings of creative work, and keep working until what we produce reflects our good taste

Recombiner

So many of us get into social media because we admire the work of creatives in the field, the brilliant memes, the awe inspiring videos, the perspective altering tweets. But there’s a gap when we start. What we produce doesn’t live up to our own expectations. Our taste exceeds our ability.

“A lot of people never get past this phase," notes Ira Glass because they succumb to the disappointment of producing work that doesn’t match up to the sky-high expectations set by their taste. Every creative has at least once considered packing it in and pursuing the most un-creative career trajectory possible, simply to avoid the heartbreak of knowing their work doesn’t quite cut it.

by Recombiner

“In the beginning, and for a while afterwards we know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have,” says Glass. “We all go through this. And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know it’s normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. It’s gonna take a while. It’s normal to take a while. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.”

It’s tempting sometimes just to stop trying to be excellent, to start filling the content calendar with “content” rather than striving for the breakthrough executions that get noticed and engaged with. So even as you cringe at your first attempts, recognise the taste gap. Then get back to writing your headline 25 times until it’s as catchy as it can be.

And maybe - if you work damn hard at it - your ability will catch up with your taste.

Ira Glass on the Creative Process:

Related Skill

Book a course related to this article:

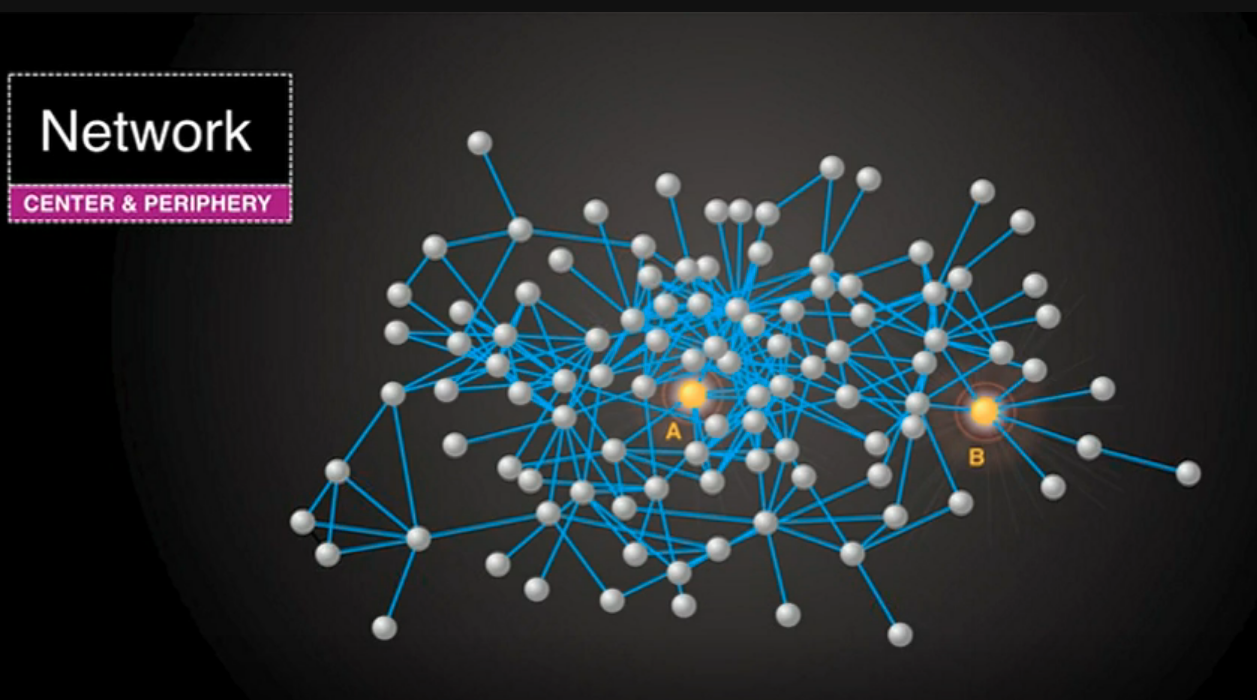

The simple trick to finding the most connected and influential people in a social network

We're all embedded in vast social networks of friends, family, co-workers and more. Nicholas Christakis tracks how a wide variety of traits can spread from person to person, showing how your location in the network might impact your life in ways you don't even know. Christakis highlights how new forms of data collection allow us to locate the central people within a network and ultimately "use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being."

We're all embedded in vast social networks of friends, family, co-workers and more. Nicholas Christakis tracks how a wide variety of traits -- from happiness to obesity -- can spread from person to person, showing how your location in the network might impact your life in ways you don't even know. Christakis highlights how new forms of data collection allow us to locate the central people within a network and ultimately "use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being."

For the last 10 years, I've been spending my time trying to figure out how and why human beings assemble themselves into social networks. And the kind of social network I'm talking about is not the recent online variety, but rather, the kind of social networks that human beings have been assembling for hundreds of thousands of years, ever since we emerged from the African savannah. So, I form friendships and co-worker and sibling and relative relationships with other people who in turn have similar relationships with other people. And this spreads on out endlessly into a distance. And you get a network that looks like this. Every dot is a person. Every line between them is a relationship between two people -- different kinds of relationships. And you can get this vast fabric of humanity, in which we're all embedded.

My colleague, James Fowler and I have been studying for quite sometime what are the mathematical, social, biological and psychological rules that govern how these networks are assembled and what are the similar rules that govern how they operate, how they affect our lives. But recently, we've been wondering whether it might be possible to take advantage of this insight, to actually find ways to improve the world, to do something better, to actually fix things, not just understand things.

So one of the first things we thought we would tackle would be how we go about predicting epidemics.

And the current state of the art in predicting an epidemic -- if you're the CDC or some other national body -- is to sit in the middle and collect data from physicians and laboratories in the field that report the prevalence or the incidence of certain conditions. These data are fed into a central repository, with some delay. And if everything goes smoothly, one to two weeks from now you'll know where the epidemic was today. And actually, about a year or so ago, there was this promulgation of the idea of Google Flu Trends, with respect to the flu, where by looking at people's searching behavior today, we could know what the status of the epidemic was today, what's the prevalence of the epidemic today.

But what I'd like to show you is a means by which we might get not just rapid warning about an epidemic, but also actually early detection of an epidemic. And, in fact, this idea can be used not just to predict epidemics of germs, but also to predict epidemics of all sorts of kinds. For example, anything that spreads by a form of social contagion could be understood in this way, from abstract ideas on the left like patriotism, or altruism, or religion to practices like dieting behavior, or book purchasing, or drinking, or products that people might buy, purchases of electronic goods, anything in which there's kind of an interpersonal spread.

A kind of a diffusion of innovation could be understood and predicted by the following mechanism.

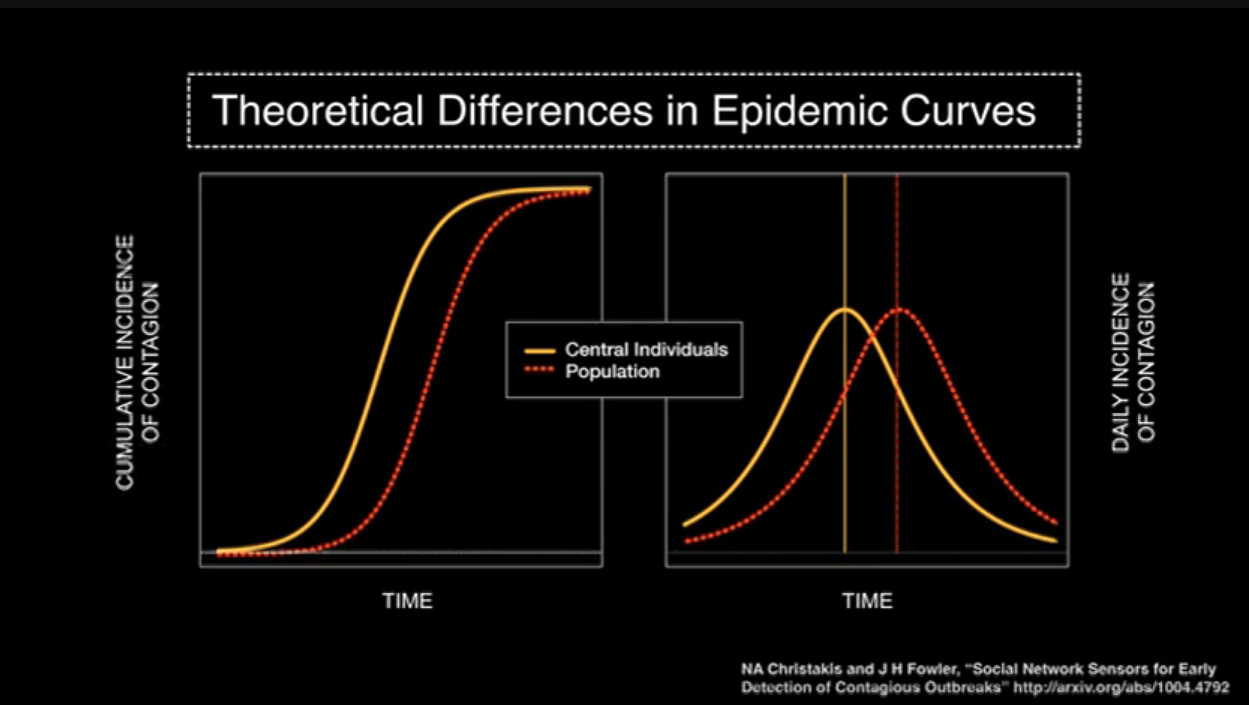

As you probably know, the classic way of thinking about this is the diffusion-of-innovation, or the adoption curve. So here on the Y-axis, we have the percent of the people affected, and on the X-axis, we have time. And at the very beginning, not too many people are affected, and you get this classic sigmoidal, or S-shaped, curve. And the reason for this shape is that at the very beginning, let's say one or two people are infected, or affected by the thing and then they affect, or infect, two people, who in turn affect four, eight, 16 and so forth, and you get the epidemic growth phase of the curve. And eventually, you saturate the population. There are fewer and fewer people who are still available that you might infect, and then you get the plateau of the curve, and you get this classic sigmoidal curve. And this holds for germs, ideas, product adoption, behaviors, and the like.

But things don't just diffuse in human populations at random. They actually diffuse through networks. Because we live our lives in networks, and these networks have a particular kind of a structure.

Now if you look at a network like this - this is 105 people. The dots are the people, and the lines represent friendship relationships. You might see that people occupy different locations within the network. And there are different kinds of relationships between the people. You could have friendship relationships, sibling relationships, spousal relationships, co-worker relationships, neighbor relationships and the like. And different sorts of things spread across different sorts of ties. For instance, sexually transmitted diseases will spread across sexual ties. Or, for instance, people's smoking behavior might be influenced by their friends. Or their altruistic or their charitable giving behavior might be influenced by their coworkers, or by their neighbors.

But not all positions in the network are the same.

If you look at this, you might immediately grasp that different people have different numbers of connections. Some people have one connection, some have two, some have six, some have 10 connections. This is called the "degree" of a node, or the number of connections that a node has.

But in addition, there's something else.

If you look at nodes A and B, they both have six connections. But if you can see this image [of the network] from a bird's eye view, you can appreciate that there's something very different about nodes A and B.

So, let me ask you this -- who would you rather be if a deadly germ was spreading through the network, A or B? B, it's obvious. B is located on the edge of the network. Now, who would you rather be if a juicy piece of gossip were spreading through the network? A. A is going to be more likely to get the thing that's spreading and to get it sooner by virtue of their structural location within the network. A, in fact, is more central, and this can be formalised mathematically.

So, if we want to track something that was spreading through a network, what we ideally would like to do is to set up sensors on the central individuals within the network, including node A, monitor those people that are right there in the middle of the network, and somehow get an early detection of whatever it is that is spreading through the network.

If you saw them contract a germ or a piece of information, you would know that, soon enough, everybody was about to contract this germ or this piece of information. If you could do that, what you would see is something like this. On the left-hand panel, again, we have the S-shaped curve of adoption. In the dotted red line, we show what the adoption would be in the random people, and in the left-hand line, shifted to the left, we show what the adoption would be in the central individuals within the network. On the Y-axis is the cumulative instances of contagion, and on the X-axis is the time. And on the right-hand side, we show the same data, but here with daily incidence. But shifted to the left is what's occurring in the central individuals. And this difference in time between the two is the early detection, the early warning we can get, about an impending epidemic in the human population.

The problem, however, is that mapping human social networks is not always possible. It can be expensive, not feasible, unethical, or, frankly, just not possible to do such a thing.

So, how can we figure out who the central people are in a network without actually mapping the network?

What we came up with was an idea to exploit an old fact about social networks, which goes like this: Do you know that your friends have more friends than you do? This is known as the friendship paradox. Imagine a very popular person in the social network -- like a party host who has hundreds of friends -- and a misanthrope who has just one friend, and you pick someone at random from the population; they were much more likely to know the party host. And if they nominate the party host as their friend, that party host has a hundred friends, therefore, has more friends than they do. And this, in essence, is what's known as the friendship paradox. The friends of randomly chosen people have higher degree, and are more central than the random people themselves.

And you can get an intuitive appreciation for this if you imagine just the people at the perimeter of the network. If you pick this person, the only friend they have to nominate is this person who, by construction, must have at least two and typically more friends. And that happens at every peripheral node. In fact, it happens throughout the network you move in -- when a random person nominates a friend of theirs, you move closer to the center of the network. So, we thought we would exploit this idea in order to study whether we could predict phenomena within networks. Because now, with this idea we can take a random sample of people, have them nominate their friends, those friends would be more central, and we could do this without having to map the network.

And we tested this idea with an outbreak of H1N1 flu at Harvard College in the fall and winter of 2009:

We took 1,300 randomly selected undergraduates, we had them nominate their friends, and we followed both the random students and their friends daily in time to see whether or not they had the flu epidemic. And we did this passively by looking at whether or not they'd gone to university health services. We also had them [actively] email us a couple of times a week.

Exactly what we predicted happened.

The random group is in the red line. The epidemic in the friends group has shifted to the left, over here. And the difference in the two is 16 days. By monitoring the friends group, we could get 16 days advance warning of an impending epidemic in this human population.

I should say that how far advanced a notice one might get about something depends on a host of factors. It could depend on the nature of the pathogen -- different pathogens, using this technique, you'd get different warning -- or other phenomena that are spreading, or frankly, on the structure of the human network. In our case, although it wasn't necessary, we could also actually map the network of the students.

As I've been suggesting, this method is not restricted to germs, but actually to anything that spreads in populations. Information spreads in populations, norms can spread in populations, behaviors can spread in populations. And by behaviors, I can mean things like criminal behavior, or voting behavior, or health care behavior, like smoking, or vaccination, or product adoption, or other kinds of behaviors that relate to interpersonal influence. If I'm likely to do something that affects others around me, this technique can get early warning or early detection about the adoption within the population. The key thing is that for it to work, there has to be interpersonal influence. It cannot be because of some broadcast mechanism affecting everyone uniformly.

Similar ideas can be used, for instance, to target distribution of things like bed nets in the developing world. If we could understand the structure of networks in villages, we could target to whom to give the interventions to foster these kinds of spreads. Or, frankly, for advertising with all kinds of products. If we could understand how to target, it could affect the efficiency of what we're trying to achieve. And in fact, we can use data from all kinds of sources nowadays [to do this].

This is a map of eight million phone users in a European country. Every dot is a person, and every line represents a volume of calls between the people. And we can use such data, that's being passively obtained, to map these whole countries and understand who is located where within the network. Without actually having to query them at all, we can get this kind of a structural insight. Other sources of information are available about such features, from email interactions, online interactions, online social networks and so forth. In fact, we are in the era of what I would call "massive-passive" data collection efforts. They're all kinds of ways we can use massively collected data to create sensor networks to follow the population, understand what's happening in the population, and intervene in the population for the better. Because these new technologies tell us not just who is talking to whom, but where everyone is, and what they're thinking based on what they're uploading on the Internet, and what they're buying based on their purchases. All this administrative data can be pulled together and processed to understand human behavior in a way we never could before.

There are three ways that these massive-passive data can be used.

Fully passive, where we don't actually intervene in the population in any way.

Quasi-active, like the flu example, where we get some people to nominate their friends and then passively monitor their friends -- do they have the flu, or not? -- and then get warning.

Fully active where people might globally participate in wikis, or photographing, or monitoring elections, and upload information in a way that allows us to pool information in order to understand social processes and social phenomena.

In fact, the availability of these data, heralds a kind of new era of what I and others would like to call "computational social science." Now we have access to these kinds of data that allow us to understand social processes and social phenomena in an entirely new way that was never before possible. With this science, we can understand how exactly the whole comes to be greater than the sum of its parts. And actually, we can use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is an internist and social scientist who conducts research on social factors that affect health, health care, and longevity. He is Professor of Medical Sociology in the Department of Health Care Policy at Harvard Medical School; Professor of Medicine in the Department of Medicine at Harvard Medical School; Professor of Sociology in the Department of Sociology in the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences; and an Attending Physician (with an emphasis on palliative medicine) in the Department of Medicine at the Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

This is an extract from a 2010 talk delivered by Nicholas Christakis entitled "How social networks predict epidemics" delivered at TED@Cannes, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Related Skill

Book a class related to this article:

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is busy loading, please upgrade your infrastructure ████░░░░░░░░░ 33%

We are realising the limits of virtualisation. We still need to grow real food, wear real clothes, move real things around in the real world. And the way we do that hasn't changed fundamentally in the past 50 years. The internet has given us a new operating system, but it’s time to upgrade our hardware.

by Dave Duarte

Apple, Google, Tencent, Microsoft, Samsung. The leaders of the digital revolution. They've displaced the bastions of the pre-digital economy for the top spots in the most valuable companies list, and virtualised the way we shop, play, bank, and more.

All this, and yet we are realising the limits of virtualisation. We still need to grow real food, wear real clothes, move real things around in the real world. And the way we do that hasn't changed fundamentally in the past 50 years. We're still dependent on the oil-powered logistics network of the 20th century. In other words, we have a new operating system running on old hardware.

The industries that can be easily virtualised have streaked ahead, leaving the old economy flailing. Youth unemployment is on the rise, GDP around the world is slowing, and tensions are escalating as demand for scarce resources increases faster than our current production capacity. This is why we are seeing the rise of populism again, as people become desperate to vote for leaders who promise them radical economic transformation.

According the renowned economist Jeremy Rifkin, we will only experience radical economic transformation when we have a convergence of next-generation infrastructure in three fields: 1. Communications, 2. Energy, and 3. Transport.

In other words, now is not the time to get complacent about change. It is upgrade or die.

The Three Industrial Revolutions to Date

Let's go back in history for a moment to illustrate.

In the First Industrial Revolution of the 19th Century you have the printing press in Communications (it's been around for a couple of centuries already); but then in Energy, you have steam power so you can power this printing press to produce greater volumes of literature cheaper and faster; and then in Transportation you have locomotion, which helps transport that literature globally.

Innovation booms. And a sustainable shift happens as print technology is introduced into public schools, allowing for a workforce that was more literate than ever before, and ultimately equipped to manage the ever-growing coal and rail infrastructure.

“We couldn’t have done it with an illiterate workforce,” Rifkin states, highlighting just how important this convergence was for the success of the First industrial Revolution.

Moving to the Second Industrial Revolution, things speed up even more. This is all about bringing the advanced technologies of the day to more people.

In Communications we see the telephone network - people can coordinate production and trade across vast distances in real time. A game changer!

In Energy we witness the centralisation of electricity, thanks to the creation of an energy distribution grid. Startup costs plummet, factories pop up everywhere.

And of course, in Transport, the factory-made automobile changes everything.

Combine these major breakthroughs with radio and television and we see suburban society mass consumer culture, and an unprecedented rise in living standards. Major level up.

The third industrial revolution has transformed communications, media, and finance. This thanks largely to the upgrade in Communications infrastructure. And yet we haven't seen the same step change in the other two major infrastructures: transport and energy.

The auto-oil industrial complex of the 20th century is on its last legs. Fossil fuels are increasingly expensive and environmentally unsustainable. Expensive Infrastructure investments in coal, oil and gas are looking less like sure bets, and so the old infrastructure is crumbling.

You can have market reforms, labour reforms, fiscal reforms, new kinds of incentives for entrepreneurs, but as long as you are building on this old system, aggregate efficiency is going to remain stuck.

Time for a Systems Upgrade

Using Rifkin's model, it's plain that the key to unlocking the Fourth Industrial Revolution is in not just Renewable Energy, and Electric Vehicles, but in the infrastructure that enables those networks to function in a decentralised way.

Let's paint the picture: You have renewable energy that is already cheaper per MW than fossil fuels. You have electric vehicles that can be powered by this essentially limitless energy source; and you can connect these systems to the internet, which allows for remote coordination, automation, and machine learning to make the whole system much more efficient.

That efficiency will be translated in terms of much lower cost prices for everything - from food staples to clothing and more. This means things are more affordable for more people, and the world becomes more inclusive (again - just like previous industrial revolutions).

What about the Jobs?

This global network of internet connected cities, vehicles, buildings, and objects is going to require a LOT of human work to be built. We are talking new factories, new service businesses, plumbers installing sensors, electricians upgrading homes and offices.

"We are in a position fundamentally shift and revitalise the global economy," says Rifkin.

The current system cannot sustain growing demand for resources. Instability, youth unemployment, environmental change, and inequality demand a systems scale shift. This shift won't happen by itself, it requires bold, determined investment in the new infrastructure.

This is not just an opportunity for growth, it is a necessity for social inclusion, environmental sustainability and global peace.

Related Skill

Book a class related to this article:

Want to get great at something? Get a coach

How do we improve in the face of complexity? Atul Gawande has studied this question with a surgeon's precision. He shares what he's found to be the key: having a good coach to provide a more accurate picture of our reality, to instill positive habits of thinking, and to break our actions down and then help us build them back up again. "It's not how good you are now; it's how good you're going to be that really matters," Gawande says.

How do we improve in the face of complexity? Atul Gawande has studied this question with a surgeon's precision. He shares what he's found to be the key: having a good coach to provide a more accurate picture of our reality, to instil positive habits of thinking, and to break our actions down and then help us build them back up again. "It's not how good you are now; it's how good you're going to be that really matters," Gawande says.

By Atul Gawande

How do professionals get better at what they do? How do they get great? I think it's not just how good you are now, I think it's how good you're going to be that really matters. As a surgeon getting better means I save more lives. And I have also seen the consequences of different philosophies of betterment around the world. I'd like to share what I have observed.

Dorothy DeLay with students

The Two Views of Professional Improvement

There are two views about this. One is the traditional pedagogical view. That is that you go to school, you study, you practice, you learn, you graduate, and then you go out into the world and you make your way on your own. A professional is someone who is capable of managing their own improvement. That is the approach that virtually all professionals have learned by. That's how doctors learn, that's how lawyers do, scientist, and musicians. And the thing is, it works. Consider for example legendary Juilliard violin instructor Dorothy DeLay. She trained an amazing roster of violin virtuosos: Midori, Sarah Chang, Itzhak Perlman. Each of them came to her as young talents, and they worked with her over years. What she worked on most, she said, was inculcating in them habits of thinking and of learning so that they could make their way in the world without her when they were done.

Now, the contrasting view comes out of sports. And they say "You are never done, everybody needs a coach." Everyone. The greatest in the world needs a coach.

So I tried to think about this as a surgeon. Pay someone to come into my operating room, observe me and critique me. That seems absurd. Expertise means not needing to be coached

So then which view is right?

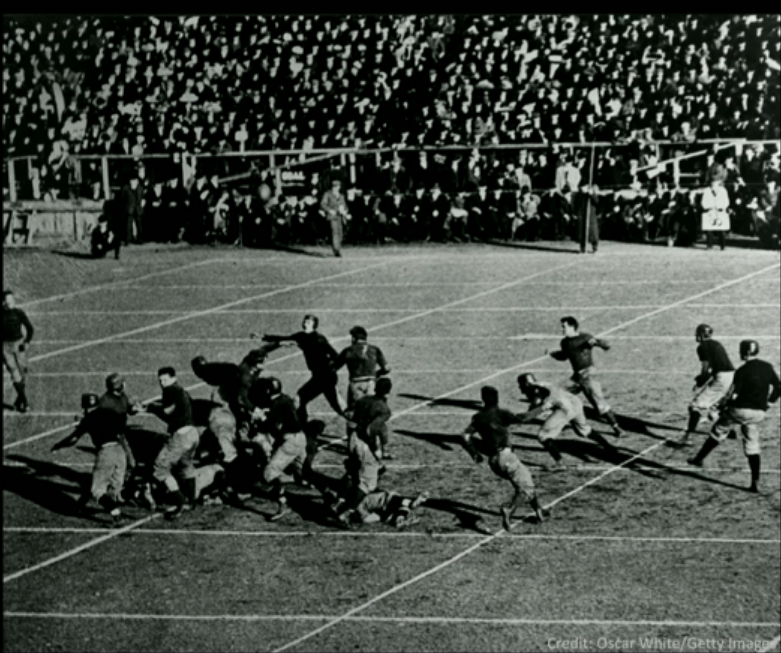

I learned that coaching came into sports as a very American idea. In 1875, Harvard and Yale played one of the very first American-rules football games. Yale hired a head coach; Harvard did not. The results? Over the next three decades, Harvard won just four times. Harvard hired a coach.

And it became the way that sports works. But is it necessary then? Does it transfer into other fields?

Itzhak Perlman

I decided to ask, of all people, Itzhak Perlman. He had trained the Dorothy DeLay way and became arguably the greatest violinist of his generation. One of the beautiful things about getting to write for "The New Yorker" is I call people up, and they return my phone calls.

And Perlman returned my phone call. So we ended up having an almost two-hour conversation about how he got to where he got in his career.

And I asked him, I said, "Why don't violinists have coaches?"

And he said, "I don't know, but I always had a coach."

"You always had a coach?"

"Oh yeah, my wife, Toby."

They had graduated together from Juilliard, and she had given up her job as a concert violinistto be his coach, sitting in the audience, observing him and giving him feedback.

"Itzhak, in that middle section, you know you sounded a little bit mechanical. What can you differently next time?" It was crucial to everything he became, he said.

My Own Coaching Experience

Turns out there are numerous problems in making it on your own. You don't recognize the issues that are standing in your way or if you do, you don't necessarily know how to fix them.And the result is that somewhere along the way, you stop improving. And I thought about that, and I realised that was exactly what had happened to me as a surgeon.

I'd entered practice in 2003, and for the first several years, it was just this steady, upward improvement in my learning curve. I watched my complication rates drop from one year to the next. And after about five years, they levelled out. And a few more years after that, I realised I wasn't getting any better anymore. And I thought: "Is this as good as I'm going to get?"

So I thought a little more and I said ... "OK, I'll try a coach." So I asked a former professor of mine who had retired, his name is Bob Osteen, and he agreed to come to my operating room and observe me. The case -- I remember that first case. It went beautifully. I didn't think there would be anything much he'd have to say when we were done. Instead, he had a whole page dense with notes.

"Just small things," he said.

But it's the small things that matter. "Did you notice that the light had swung out of the wound during the case?", he asked "You spent about half an hour just operating off the light from reflected surfaces". I hadn't noticed. "Another thing," he said, "Your elbow goes up in the air every once in a while. That means you're not in full control. A surgeon's elbows should be down at their sides resting comfortably. So that means if you feel your elbow going in the air, you should get a different instrument, or just move your feet." It was a whole other level of awareness. And I had to think, there was something fundamentally profound about this.

Osteen was doing what great coaches do: they are your external eyes and ears, providing a more accurate picture of your reality. They're recognising the fundamentals. They're breaking your actions down and then helping you build them back up again.

After two months of coaching, I felt myself getting better again. And after a year, I saw my complications drop down even further. It was painful. I didn't like being observed, and at times I didn't want to have to work on things. I also felt there were periods where I would get worse before I got better. But it made me realize that the coaches were onto something profoundly important.

Systems Scale Coaching

In my other work, I lead a health systems innovation centre called Ariadne Labs, where we work on problems in the delivery of health care, including global childbirth. As part of it, we had worked with the World Health Organization to devise a safe childbirth checklist. It lays out the fundamentals -- the critical actions a team needs to go through when a woman comes in in labor; when she's ready to push; when the baby is out; and then when the mom and baby are ready to go home. And we knew that just handing out a checklist wasn't going to change very much, and even just teaching it in the classroom wasn't necessarily going to be enough to get people to make the changes that you needed to bring it alive. And I thought on my experience and said:

““What if we tried coaching? What if we tried coaching at a massive scale?””

We found some incredible partners, including the government of India, and we ran a trial in 120 birth centres. In Uttar Pradesh, in India's largest state. Half of the centres we just observed, but the other half got visits from coaches. We trained an army of doctors and nurses in basic coaching practices - observation for a start.

One of the skills, they had to work on - that turned out to be fundamentally important - was communication. Getting the nurses to practice speaking up when the baby mask is broken, or the gloves are not in stock, or someone's not washing their hands. And then getting others, including the managers, to practice listening. This small army of coaches ended up coaching 400 nurses and other birth attendants, and 100 physicians and managers. We tracked the results across 160,000 births.

The results:

- In the control group who didn't have coaching they delivered on only one-third of 18 basic practices that we were measuring. And most important was that over the course of the years of study, we saw no improvement over time.

- In the other group, who got four months of coaching, we saw them increase to greater than two-thirds of the practices being delivered. It works. We could see the improvement in quality, and you could see it happen across a whole range of centres that suggested that coaching could be a whole line of way that we bring value to what we do.

With coaching at this scale, you can imagine the whole job category that could reach out in the world and that millions of people could fulfil.

Surgeon and public health professor by day, writer by night, Atul Gawande explores how doctors can dramatically improve their practice using approaches as simple as a checklist – or coaching. Atul Gawande is author of several best-selling books, including Complications: A Surgeon's Notes on an Imperfect Science, Better: A Surgeon's Notes on Performance, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End and The Checklist Manifesto.

This is an extract from a 2017 talk delivered by Atul Gawande entitled "Want to get great at something? Get a coach" delivered at TED2017, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Dave Duarte, founder of Treeshake, is passionate about community engagement as a driver of value. As social marketer, speaker, facilitator and advisor, his warm and engaging style makes the future easy to engage with. Dave brings over a decade of facilitation experience to his work at Treeshake. He has founded several businesses, and served in leadership positions in media, academia, and non-profits.