The secret to living longer may be your social life

The Italian island of Sardinia has more than six times as many centenarians as the mainland and ten times as many as North America. Why? According to psychologist Susan Pinker, it's not a sunny disposition or a low-fat, gluten-free diet that keeps the islanders healthy -- it's their emphasis on close personal relationships and face-to-face interactions. Learn more about super longevity as Pinker explains what it takes to live to 100 and beyond.

The Italian island of Sardinia has more than six times as many centenarians as the mainland and ten times as many as North America. Why? According to psychologist Susan Pinker, it's not a sunny disposition or a low-fat, gluten-free diet that keeps the islanders healthy -- it's their emphasis on close personal relationships and face-to-face interactions. Learn more about super longevity as Pinker explains what it takes to live to 100 and beyond.

By Susan Pinker

Here's an intriguing fact: In the developed world, everywhere, women live an average of six to eight years longer than men do. In 2015, The Lancet published an article showing that men in rich countries are twice as likely to die as women are at any age.

Sardinia, Italy

But there is one place in the world where men live as long as women. It's a remote, mountainous zone, a blue zone, where super longevity is common to both sexes. This is the blue zone in Sardinia, an Italian island in the Mediterranean, between Corsica and Tunisia, where there are six times as many centenarians as on the Italian mainland, less than 200 miles away. There are 10 times as many centenarians as there are in North America. It's the only place where men live as long as women.

But why? My curiosity was piqued. I decided to research the science and the habits of the place, and I started with the genetic profile. I discovered soon enough that genes account for just 25 percent of their longevity. The other 75 percent is lifestyle.

Villagrande: Epicenter of Sardinia's Blue Zone

So what does it take to live to 100 or beyond? What are they doing right?

What you're looking at is an aerial view of Villagrande. It's a village at the epicenter of the blue zone where I went to investigate this, and as you can see, architectural beauty is not its main virtue, density is: tightly spaced houses, interwoven alleys and streets. It means that the villagers' lives constantly intersect. And as I walked through the village, I could feel hundreds of pairs of eyes watching me from behind doorways and curtains, from behind shutters. Because like all ancient villages, Villagrande couldn't have survived without this structure, without its walls, without its cathedral, without its village square, because defense and social cohesion defined its design.

Urban priorities changed as we moved towards the industrial revolution because infectious disease became the risk of the day. But what about now? Now, social isolation is the public health risk of our time. Now, a third of the population says they have two or fewer people to lean on.

But let's go to Villagrande now as a contrast to meet some centenarians.

Giuseppe Murinu

Meet Giuseppe Murinu. He's 102, a supercentenarian and a lifelong resident of the village of Villagrande. He was a gregarious man. He loved to recount stories such as how he lived like a bird from what he could find on the forest floor during not one but two world wars, how he and his wife, who also lived past 100, raised six children in a small, homey kitchen where I interviewed him. He was a happy-go-lucky guy, very outgoing with a positive outlook. And I wondered: so is that what it takes to live to be 100 or beyond, thinking positively? Actually, no.

“Building in-person interaction into our cities, into our workplaces, into our agendas bolsters the immune system, sends feel-good hormones surging through the bloodstream and brain and helps us live longer. ”

Meet Giovanni Corrias. He's 101, the grumpiest person I have ever met

Giovanni Corrias

And he put a lie to the notion that you have to be positive to live a long life. And there is evidence for this. When I asked him why he lived so long, he kind of looked at me under hooded eyelids and he growled, "Nobody has to know my secrets."

But despite being a sourpuss, the niece who lived with him and looked after him called him "Il Tesoro," "my treasure." And she respected him and loved him, and she told me, when I questioned this obvious loss of her freedom, "You just don't understand, do you? Looking after this man is a pleasure. It's a huge privilege for me. This is my heritage." And indeed, wherever I went to interview these centenarians, I found a kitchen party. And I quickly discovered by being there that in the blue zone, as people age, and indeed across their lifespans, they're always surrounded by extended family, by friends, by neighbors, the priest, the barkeeper, the grocer. People are always there or dropping by. They are never left to live solitary lives. This is unlike the rest of the developed world, where as George Burns quipped, "Happiness is having a large, loving, caring family in another city."

Zia Teresa

Now, so far we've only met men, long-living men, but I met women too, and here you see Zia Teresa. She, at over 100, taught me how to make the local specialty, which is called culurgiones, which are these large pasta pockets like ravioli and they're filled with high-fat ricotta and mint and drenched in tomato sauce. And she showed me how to make just the right crimp so they wouldn't open, and she makes them with her daughters every Sunday and distributes them by the dozens to neighbors and friends. And that's when I discovered a low-fat, gluten-free diet is not what it takes to live to 100 in the blue zone.

Now, these centenarians' stories along with the science that underpins them prompted me to ask myself some questions too, such as, when am I going to die and how can I put that day off? And as you will see, the answer is not what we expect. Julianne Holt-Lunstad is a researcher at Brigham Young University and she addressed this very question in a series of studies of tens of thousands of middle aged people much like this audience here. And she looked at every aspect of their lifestyle: their diet, their exercise, their marital status, how often they went to the doctor, whether they smoked or drank, etc. She recorded all of this and then she and her colleagues sat tight and waited for seven years to see who would still be breathing. And of the people left standing, what reduced their chances of dying the most? That was her question.

So let's now look at her data in summary, going from the least powerful predictor to the strongest. OK? So clean air, which is great, it doesn't predict how long you will live. Whether you have your hypertension treated is good. Still not a strong predictor. Whether you're lean or overweight, you can stop feeling guilty about this, because it's only in third place. How much exercise you get is next, still only a moderate predictor. Whether you've had a cardiac event and you're in rehab and exercising, getting higher now. Whether you've had a flu vaccine. Did anybody here know that having a flu vaccine protects you more than doing exercise? Whether you were drinking and quit, or whether you're a moderate drinker, whether you don't smoke, or if you did, whether you quit, and getting towards the top predictors are two features of your social life.

by: Horst Gutmann

First, your close relationships. These are the people that you can call on for a loan if you need money suddenly, who will call the doctor if you're not feeling well or who will take you to the hospital, or who will sit with you if you're having an existential crisis, if you're in despair. Those people, that little clutch of people are a strong predictor, if you have them, of how long you'll live. And then something that surprised me, something that's called social integration. This means how much you interact with people as you move through your day. How many people do you talk to? And these mean both your weak and your strong bonds, so not just the people you're really close to, who mean a lot to you, but, like, do you talk to the guy who every day makes you your coffee? Do you talk to the postman? Do you talk to the woman who walks by your house every day with her dog? Do you play bridge or poker, have a book club? Those interactions are one of the strongest predictors of how long you'll live.

by: Zohaib Akhtar Photography

Now, this leads me to the next question: if we now spend more time online than on any other activity, including sleeping, we're now up to 11 hours a day, one hour more than last year, by the way, does it make a difference? Why distinguish between interacting in person and interacting via social media? Is it the same thing as being there if you're in contact constantly with your kids through text, for example? Well, the short answer to the question is no, it's not the same thing. Face-to-face contact releases a whole cascade of neurotransmitters, and like a vaccine, they protect you now in the present and well into the future. So simply making eye contact with somebody, shaking hands, giving somebody a high-five is enough to release oxytocin, which increases your level of trust and it lowers your cortisol levels. It lowers your stress and dopamine is generated, which gives us a little high and it kills pain. It's like a naturally produced morphine.

Now, all of this passes under our conscious radar, which is why we conflate online activity with the real thing. But we do have evidence now, fresh evidence, that there is a difference. So let's look at some of the neuroscience. Elizabeth Redcay, a neuroscientist at the University of Maryland, tried to map the difference between what goes on in our brains when we interact in person versus when we're watching something that's static. And what she did was she compared the brain function of two groups of people, those interacting live with her or with one of her research associates in a dynamic conversation, and she compared that to the brain activity of people who were watching her talk about the same subject but in a canned video, like on YouTube. And by the way, if you want to know how she fit two people in an MRI scanner at the same time, talk to me later.

So what's the difference? This is your brain on real social interaction. What you're seeing is the difference in brain activity between interacting in person and taking in static content. In orange, you see the brain areas that are associated with attention, social intelligence -- that means anticipating what somebody else is thinking and feeling and planning -- and emotional reward. And these areas become much more engaged when we're interacting with a live partner.

Now, these richer brain signatures might be why recruiters from Fortune 500 companiesevaluating candidates thought that the candidates were smarter when they heard their voicescompared to when they just read their pitches in a text, for example, or an email or a letter.Now, our voices and body language convey a rich signal. It shows that we're thinking, feeling,sentient human beings who are much more than an algorithm. Now, this research by Nicholas Epley at the University of Chicago Business School is quite amazing because it tells us a simple thing. If somebody hears your voice, they think you're smarter. I mean, that's quite a simple thing.

Now, to return to the beginning, why do women live longer than men? And one major reason is that women are more likely to prioritise and groom their face-to-face relationships over their lifespans. Fresh evidence shows that these in-person friendships create a biological force field against disease and decline. And it's not just true of humans but our primate relations as well. Anthropologist Joan Silk's work shows that female baboons who have a core of female friends show lower levels of stress via their cortisol levels, they live longer and they have more surviving offspring. At least three stable relationships. That was the magic number. Think about it. I hope you guys have three.

The power of such face-to-face contact is really why there are the lowest rates of dementia among people who are socially engaged. It's why women who have breast cancer are four times more likely to survive their disease than loners are. This face-to-face contact provides stunning benefits, yet now almost a quarter of the population says they have no one to talk to.

We can do something about this. Like Sardinian villagers, it's a biological imperative to know we belong, and not just the women among us. Building in-person interaction into our cities, into our workplaces, into our agendas bolsters the immune system, sends feel-good hormones surging through the bloodstream and brain and helps us live longer. I call this building your village, and building it and sustaining it is a matter of life and death.

Susan Pinker reveals how in-person social interactions are not only necessary for human happiness but also could be a key to health and longevity. With The Village Effect, she tracks how social, face-to-face interactions are critical not only for our happiness but also for our survival, and how technology can isolate us from these life-saving bonds.

This is an extract from a 2017 talk delivered by Susan Pinker entitled "The secret to living longer may be your social life" delivered at TED2017, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

5 ways to lead in an era of constant change

Who says change needs to be hard? Organizational change expert Jim Hemerling thinks adapting your business in today's constantly-evolving world can be invigorating instead of exhausting. He outlines five imperatives, centered around putting people first, for turning company reorganization into an empowering, energizing task for all.

Who says change needs to be hard? Organizational change expert Jim Hemerling thinks adapting your business in today's constantly-evolving world can be invigorating instead of exhausting. He outlines five imperatives, centered around putting people first, for turning company reorganization into an empowering, energizing task for all.

Have you ever noticed when you ask someone to talk about a change they're making for the better in their personal lives, they're often really energetic? Whether it's training for a marathon, picking up an old hobby, or learning a new skill, for most people, self-transformation projects occupy a very positive emotional space.

When it comes to self-transformation, you can't help but get a sense of the excitement. But there's another type of transformation that occupies a very different emotional space. The transformation of organizations. If you're like most people, when you hear the words "Our organization is going to start a transformation," you're thinking, "Uh-oh."

"Layoffs." The blood drains from your face, your mind goes into overdrive, frantically searching for some place to run and hide.

Well, you can run, but you really can't hide. Most of us spend the majority of our waking hours involved in organizations. And due to changes in globalization, changes due to advances in technology and other factors, the reality is our organizations are constantly having to adapt. In fact, I call this the era of "always-on" transformation.

“People naturally resist change, especially when it’s imposed on them”

When I shared this idea with my wife Nicola, she said, "Always-on transformation? That sounds exhausting." And that may be exactly what you're thinking -- and you would be right. Particularly if we continue to approach the transformation of organizations the way we always have been.

But because we can't hide, we need to sort out two things. First, why is transformation so exhausting? And second, how do we fix it?

First of all, let's acknowledge that change is hard. People naturally resist change, especially when it's imposed on them. But there are things that organizations do that make change even harder and more exhausting for people than it needs to be. Leaders often wait too long to act. As a result, everything is happening in crisis mode. Which, of course, tends to be exhausting. Or, given the urgency, what they'll do is they'll just focus on the short-term results, but that doesn't give any hope for the future. Or they'll just take a superficial, one-off approach, hoping that they can return back to business as usual as soon as the crisis is over.

So given these obstacles, what can we do to transform the way we transform organizations so rather than being exhausting, it's actually empowering and energizing?

To do that, we need to focus on five strategic imperatives, all of which have one thing in common: putting people first.

The first imperative for putting people first is to inspire through purpose. Most transformations have financial and operational goals. These are important and they can be energizing to leaders, but they tend not to be very motivating to most people in the organization. To motivate more broadly, the transformation needs to connect with a deeper sense of purpose.

Take LEGO. The LEGO Group has become an extraordinary global company. Under their very capable leadership, they've actually undergone a series of transformations. While each of these has had a very specific focus, the North Star, linking and guiding all of them, has been Lego's powerful purpose: inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow. Expanding globally? It's not about increasing sales, but about giving millions of additional children access to LEGO building bricks. Investment and innovation? It's not about developing new products, but about enabling more children to experience the joy of learning through play. Not surprisingly, that deep sense of purpose tends to be highly motivating to LEGO's people.

Photo credit: recombiner

The second imperative for putting people first is to go all in. Too many transformations are nothing more than head-count cutting exercises; layoffs under the guise of transformation. In the face of relentless competition, it may well be that you will have to take the painful decision to downsize the organization, just as you may have to lose some weight in order to run a marathon. But losing weight alone will not get you across the finish line with a winning time. To win you need to go all in. You need to go all in. Rather than just cutting costs, you need to think about initiatives that will enable you to win in the medium term, initiatives to drive growth, actions that will fundamentally change the way the company operates, and very importantly, investments to develop the leadership and the talent.

The third imperative for putting people first is to enable people with the capabilities that they need to succeed during the transformation and beyond. Over the years I've competed in a number of triathlons. You know, frankly, I'm not that good, but I do have one distinct capability; I am remarkably fast at finding my bike.

By the time I finish the swim, almost all the bikes are already gone.

Real triathletes know that each leg -- the swim, the bike, the run -- really requires different capabilities, different tools, different skills, different techniques. Likewise when we transform organizations, we need to be sure that we're giving our people the skills and the tools they need along the way.

Chronos, a global software company, recognized the need to transfer from building products -- software products -- to building software as a service. To enable its people to take that transformation, first of all they invested in new tools that would enable their employees to monitor the usage of the features as well as customer satisfaction with the new service. They also invested in skill development, so that their employees would be able to resolve customer service problems on the spot. And very importantly, they also reinforced the collaborative behaviors that would be required to deliver an end-to-end seamless customer experience. Because of these investments, rather than feeling overwhelmed by the transformation, Chronos employees actually felt energized and empowered in their new roles.

In the era of "always-on" transformation, change is a constant.

Photo credit: recombiner

My fourth imperative therefore is to instill a culture of continuous learning. When Satya Nadella became the CEO of Microsoft in February 2014, he embarked on an ambitious transformation journey to prepare the company to compete in a mobile-first, cloud-first world. This included changes to strategy, the organization and very importantly, the culture. Microsoft's culture at the time was one of silos and internal competition -- not exactly conducive to learning. Nadella took this head-on. He rallied his leadership around his vision for a living, learning culture, shifting from a fixed mindset, where your role was to show up as the smartest person in the room, to a growth mindset, where your role was to listen, to learn and to bring out the best in people. Well, early days, Microsoft employees already noticed this shift in the culture -- clear evidence of Microsoft putting people first.

My fifth and final imperative is specifically for leaders. In a transformation, a leader needs to have a vision, a clear road map with milestones, and then you need to hold people accountable for results. In other words, you need to be directive. But in order to capture the hearts and minds of people, you also need to be inclusive. Inclusive leadership is critical to putting people first.

In the era of "always-on" transformation, organizations are always going to be transforming. But doing so does not have to be exhausting.

We owe it to ourselves, to our organizations and to society more broadly to boldly transform our approach to transformation. To do that, we need to start putting people first.

Jim Hemerling is a Senior Partner and Managing Director in The Boston Consulting Group's People & Organization and Transformation Practices. He is a BCG Fellow with a focus on high-performance organization transformation. He also leads BCG's global Behavior & Culture topic.

This is an extract from a 2016 talk delivered by Jim Hemerling entitled "5 ways to lead in an era of constant change" delivered at TED@BCG Paris, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

If a story moves you, act on it

Stories are necessary, but they're not as magical as they seem, says writer Sisonke Msimang. In this funny and thoughtful talk, Msimang questions our emphasis on storytelling and spotlights the decline of facts. During a critical time when listening has been confused for action, Msimang asks us to switch off our phones, step away from our screens and step out into the real world to create a plan for justice.

Stories are necessary, but they're not as magical as they seem, says writer Sisonke Msimang. In this funny and thoughtful talk, Msimang questions our emphasis on storytelling and spotlights the decline of facts. During a critical time when listening has been confused for action, Msimang asks us to switch off our phones, step away from our screens and step out into the real world to create a plan for justice.

I'm here to talk about my own observations about storytelling. I want to talk to you about the power of stories, of course, but I also want to talk about their limitations, particularly for those of us who are interested in social justice.

Stories are everywhere, and if there was a danger in the telling of one tired old tale, then I think there has got to be lots to celebrate about the flourishing of so many stories and so many voices. Stories are the antidote to bias. In fact, today, if you are middle class and connected via the internet, you can download stories at the touch of a button or the swipe of a screen. You can listen to a podcast about what it's like to grow up Dalit in Kolkata. You can hear an indigenous man in Australia talk about the trials and triumphs of raising his children in dignity and in pride. Stories make us fall in love. They heal rifts and they bridge divides. Stories can even make it easier for us to talk about the deaths of people in our societies who don't matter, because they make us care. Right?

“If it is justice that we are after, then I think we mustn’t focus on the media or the storytellers. We must focus on audiences, on anyone who has ever turned on a radio or listened to a podcast, and that means all of us”

I'm not so sure, and I actually work for a place called the Centre for Stories. And my job is to help to tell stories that challenge mainstream narratives about what it means to be black or a Muslim or a refugee or any of those other categories that we talk about all the time. But I come to this work after a long history as a social justice activist, and so I'm really interested in the ways that people talk about nonfiction storytelling as though it's about more than entertainment, as though it's about being a catalyst for social action. It's not uncommon to hear people say that stories make the world a better place. Increasingly, though, I worry that even the most poignant stories, particularly the stories about people who no one seems to care about, can often get in the way of action towards social justice. Now, this is not because storytellers mean any harm. Quite the contrary. Storytellers are often do-gooders like me and, I suspect, yourselves. And the audiences of storytellers are often deeply compassionate and empathetic people. Still, good intentions can have unintended consequences, and so I want to propose that stories are not as magical as they seem.

So three -- because it's always got to be three -- three reasons why I think that stories don't necessarily make the world a better place.

Firstly,

stories can create an illusion of solidarity. There is nothing like that feel-good factor you get from listening to a fantastic story where you feel like you climbed that mountain, right, or that you befriended that death row inmate. But you didn't. You haven't done anything. Listening is an important but insufficient step towards social action.

Secondly,

I think often we are drawn towards characters and protagonists who are likable and human. And this makes sense, of course, right? Because if you like someone, then you care about them. But the inverse is also true. If you don't like someone, then you don't care about them. And if you don't care about them, you don't have to see yourself as having a moral obligation to think about the circumstances that shaped their lives.

Thirdly,

I think that stories don't necessarily make the world a better place because too often we are so invested in the personal narrative that we forget to look at the bigger picture. And so we applaud someone when they tell us about their feelings of shame, but we don't necessarily link that to oppression. We nod understandingly when someone says they felt small, but we don't link that to discrimination. The most important stories, especially for social justice, are those that do both, that are both personal and allow us to explore and understand the political.

Photo credit: recombiner

But it's not just about the stories we like versus the stories we choose to ignore.

Increasingly, we are living in a society where there are larger forces at play, where stories are actually for many people beginning to replace the news. We live in a time where we are witnessing the decline of facts, when emotions rule and analysis, it's kind of boring, right? Where we value what we feel more than what we actually know. A recent report by the Pew Center on trends in America indicates that only 10 percent of young adults under the age of 30 "place a lot of trust in the media." Now, this is significant. It means that storytellers are gaining trust at precisely the same moment that many in the media are losing the confidence in the public. This is not a good thing, because while stories are important and they help us to have insights in many ways, we need the media. From my years as a social justice activist, I know very well that we need credible facts from media institutions combined with the powerful voices of storytellers. That's what pushes the needle forward in terms of social justice.

In the final analysis, of course, it is justice that makes the world a better place, not stories. Right? And so if it is justice that we are after, then I think we mustn't focus on the media or on storytellers. We must focus on audiences, on anyone who has ever turned on a radio or listened to a podcast, and that means all of us.

So a few concluding thoughts on what audiences can do to make the world a better place:

- The world would be a better place, I think, if audiences were more curious and more skeptical and asked more questions about the social context that created those stories that they love so much.

- The world would be a better place if audiences recognized that storytelling is intellectual work. And I think it would be important for audiences to demand more buttons on their favorite websites, buttons for example that say, "If you liked this story, click here to support a cause your storyteller believes in." Or "click here to contribute to your storyteller's next big idea." Often, we are committed to the platforms, but not necessarily to the storytellers themselves.

- I think that audiences can make the world a better place by switching off their phones, by stepping away from their screens and stepping out into the real world beyond what feels safe.

Alice Walker has said, "Look closely at the present you are constructing. It should look like the future you are dreaming."

Storytellers can help us to dream, but it's up to all of us to have a plan for justice.

Sisonke Msimang tells stories about justice and human rights. In the early part of her career, Msimang set up a fund fight for people whose health had been compromised by their race, class and gender identities. In 2008 she became the executive director of the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, responsible for making grants on human rights projects. Msimang is now the head of programs at the Centre for Stories, a new initiative that collects, preserves and shares stories about migrants, refugees and diverse people and places linked to the Indian Ocean Rim.

This is an extract from a 2016 talk delivered by Sisonke Msimang entitled "If a story moves you, act on it" delivered at TEDWomen, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

What do we do with all this big data?

Does a set of data make you feel more comfortable? More successful? Then your interpretation of it is likely wrong. In a surprisingly moving talk, Susan Etlinger explains why, as we receive more and more data, we need to deepen our critical thinking skills. Because it's hard to move beyond counting things to really understanding them.

Does a set of data make you feel more comfortable? More successful? Then your interpretation of it is likely wrong. In a surprisingly moving talk, Susan Etlinger explains why, as we receive more and more data, we need to deepen our critical thinking skills. Because it's hard to move beyond counting things to really understanding them.

Technology has brought us so much: the moon landing, the Internet, the ability to sequence the human genome. But it also taps into a lot of our deepest fears, and about 30 years ago, the culture critic Neil Postman wrote a book called "Amusing Ourselves to Death," which lays this out really brilliantly, comparing the dystopian visions of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley. He said, Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture. Orwell feared the truth would be concealed from us, and Huxley feared we would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. In a nutshell, it's a choice between Big Brother watching you and you watching Big Brother.

But it doesn't have to be this way. We are not passive consumers of data and technology. We shape the role it plays in our lives and the way we make meaning from it, but to do that, we have to pay as much attention to how we think as how we code. We have to ask questions, and hard questions, to move past counting things to understanding them. We're constantly bombarded with stories about how much data there is in the world, but when it comes to big data and the challenges of interpreting it, size isn't everything. There's also the speed at which it moves, and the many varieties of data types. What unites this disparate types of data is that they're created by people and they require context.

It's not just big data that causes challenges of interpretation, because let's face it, we human beings have a very rich history of taking any amount of data, no matter how small, and screwing it up. Many years ago, you may remember that former President Ronald Reagan was very criticized for making a statement that facts are stupid things. And it was a slip of the tongue, let's be fair. He actually meant to quote John Adams' defense of British soldiers in the Boston Massacre trials that facts are stubborn things. But I actually think there's a bit of accidental wisdom in what he said, because facts are stubborn things, but sometimes they're stupid, too.

“The challenge is that we have this opportunity to make meaning out of data ourselves, because frankly, data doesn’t create meaning... we have a responsibility to spend more time focusing on our critical thinking skills”

Facts are stupid things. And they're vulnerable to misuse, willful or otherwise. I have a friend, Emily Willingham, who's a scientist, and she wrote a piece for Forbes not long ago entitled "The 10 Weirdest Things Ever Linked to Autism." It's quite a list. The Internet, blamed for everything, right? And of course mothers... there's a whole bunch in the "mother" category here. And you can see it's a pretty rich and interesting list. I'm a big fan of being pregnant near freeways, personally. The final one is interesting, because the term "refrigerator mother" was actually the original hypothesis for the cause of autism, and that meant somebody who was cold and unloving.

And at this point, you might be thinking, "Okay, Susan, we get it, you can take data, you can make it mean anything." And this is true, it's absolutely true, but the challenge is that we have this opportunity to try to make meaning out of it ourselves, because frankly, data doesn't create meaning. We do. So as businesspeople, as consumers, as patients, as citizens, we have a responsibility, I think, to spend more time focusing on our critical thinking skills.

Why?

Because at this point in our history, as we've heard many times over, we can process exabytes of data at lightning speed, and we have the potential to make bad decisions far more quickly, efficiently, and with far greater impact than we did in the past. Great, right? And so what we need to do instead is spend a little bit more time on things like the humanities and sociology, and the social sciences, rhetoric, philosophy, ethics, because they give us context that is so important for big data, and because they help us become better critical thinkers. Because after all, if I can spot a problem in an argument, it doesn't much matter whether it's expressed in words or in numbers. And this means teaching ourselves to find those confirmation biases and false correlations.

And it means questioning disciplines like demographics. Why? Because they're based on assumptions about who we all are based on our gender and our age and where we live as opposed to data on what we actually think and do. And since we have this data, we need to treat it with appropriate privacy controls and consumer opt-in, and beyond that, we need to be clear about our hypotheses, the methodologies that we use, and our confidence in the result. As my high school algebra teacher used to say, show your math, because if I don't know what steps you took, I don't know what steps you didn't take, and if I don't know what questions you asked, I don't know what questions you didn't ask. And it means asking ourselves the hardest question of all:

Did the data really show us this, or does the result make us feel more successful and more comfortable?

If we are to unlock the power of data, we don't have to go blindly into Orwell's vision of a totalitarian future, or Huxley's vision of a trivial one, or some horrible cocktail of both. What we have to do is treat critical thinking with respect and, as they say in the superhero movies, let's use our powers for good.

Susan Etlinger is an industry analyst with Altimeter Group, where she focuses on data and analytics. She conducts independent research and has authored two intriguing reports: “The Social Media ROI Cookbook” and “A Framework for Social Analytics.” She also advises global clients on how to work measurement into their organizational structure and how to extract insights from the social web which can lead to tangible actions.

This is an extract from a 2014 talk delivered by Susan Etlinger entitled "What do we do with all this big data?" delivered at TED@IBM, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Future Skills for Inclusion

The technological world is growing faster than ever, bringing the Fourth Industrial Revolution even closer to being our reality. The First Industrial Revolution brought us mechanisation, the Second brought mass production and the Third introduced computers and automation. But what about the Fourth Industrial Revolution? What does it entail and what does it mean for us?

On Wednesday, 9 May 2018, the World Economic Forum led the Shaping Inclusive Growth in The Fourth Industrial Revolution workshop. Key thinkers explored and discussed what facets of The Fourth Industrial Revolution can harness and promote inclusive growth in Africa. Below is an overview of the central ideas surrounding the Fourth Industrial Revolution and its numerous implications:

The technological world is growing faster than ever, bringing the Fourth Industrial Revolution even closer to being our reality. The First Industrial Revolution brought us mechanisation, the Second brought mass production and the Third introduced computers and automation. But what about the Fourth Industrial Revolution? What does it entail and what does it mean for us?

The World Economic Forum (WEF), in the 2018 Readiness for the Future of Production Report, described the core features of the Fourth Industrial Revolution as follows:

“Technologies are transcending the computing capabilities associated with the digital revolution, transforming the physical world through robotics and new methods of production; enhancing human beings physically, mentally, and experientially; and permeating the environment to facilitate greater interconnectivity, monitoring, and efficiency of resource use”

Put simply, the world’s technologies are developing incredibly quickly, in a variety of ways, and it is largely positive - there are innumerable benefits that this sort of technological transformation can bring, but the way we live and work will have to change in the process. One of the biggest fears regarding the Fourth Industrial Revolution and its implications, is that people will lose their jobs, en masse. And it is a scary thought to imagine a bunch of really advanced machines and AI systems developing to the point where they replace you. WEF noted that these technological developments “...are spurring the development of new production techniques, business models, and value chains that will fundamentally transform global production” (Readiness for the Future of Production Report, 2018). In other words, the Fourth Industrial Revolution does mean massive change in terms of jobs and, more generally, the way global production is conducted.

But that is not the end of the story - thankfully, the Fourth Industrial Revolution doesn’t have to mean that a machine comes along, steals your job and leaves you in the dust. It does, however, mean that we need to shift the way we look at jobs, education and skills in order to be equipped to both differentiate ourselves from machines, as well as complement their abilities. Of course this requires individuals to be proactive in their own skill development, but WEF also notes that:

“...countries need to build awareness of the changing nature of production, determine how to best prepare to benefit from this transformation and collaborate across the public and private sector to enhance readiness”

Seems obvious, right? Prepare for the Fourth Industrial Revolution as we see it on the horizon, and make sure your country and citizens are skilled enough to benefit from it instead of suffer. Unfortunately, no one is there yet and “no country has reached the frontier of readiness, let alone harnessed the full potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution in production” (WEF, 2018). With technological development moving as quickly as it is, it’s imperative for countries to adapt and change in ways that not only welcomes this progress, but take full advantage of the opportunities that will come with it. This means investing time, money and significant energy in reskilling people to leave replaceable jobs behind, and become invaluable in their differentiation from machines.

“Moving forward, people, employers and policy makers alike need to realise that success in the Fourth Industrial Revolution lies in the individual’s ability to both differentiate from and complement machines”

So, we know what the Fourth Industrial Revolution is, what it’s implications are and what we should be doing, but what is really happening around the world? People are scared. Scared about the fact that “disruptive technological and socio-economic forces threaten to swiftly outdate the shelf life of people’s skillsets and the relevance of what they thought they knew about the path to social mobility and rewarding employment,” and this is in part because of a lack of “willingness to make a reasonable investment in reskilling that will bridge workers onto new jobs” (WEF, 2018). This needs to change because employers simply cannot maintain hiring an entirely new workforce each time a new skill set is required. Rather, there needs to be an increased focus on “reskilling and human capital development.” Workers should also be actively engaged in developing their skill-set, as it removes job insecurity to a large degree, and opens the door to a range of job and career opportunities that are likely more meaningful, stable and fulfilling. Who wants to do a job that a machine can do, anyway?

The world is changing, and The Fourth Industrial Revolution is bringing of the most transformational developments to our lives. Moving forward, people, employers and policy-makers alike need to realise that success in the Fourth Industrial Revolution lies in the individual’s ability to both differentiate from and complement machines, working with them rather than in opposition to them. WEF notes that a key facet of The Fourth Industrial Revolution is the uncertainty of it, specifically because we are not even aware of what skills will be essential in the future.

Preparation is necessary, as WEF notes in their 2018 Towards a Reskilling Revolution Insight report:

“To make reskilling real, and prepare for accelerated structural change of the labour market, a wide range of stakeholders — governments, employers, individuals, educational institutions and labour unions, among others — will need to learn to come together, collaborate and pool their resources more than ever before.”

The longevity of stories

We need stories. To communicate, to understand, to relate to each other, to explain. People have, throughout time and history, incorporated storytelling (and storymaking) into their lives, because it's how we make sense of the dynamic, often complex, situations we find ourselves in. Neil Gaiman, a master storyteller, outlines the importance of a good story, and the ability stories have to shape culture and behaviour

We need stories. To communicate, to understand, to relate to each other, to explain. People have, throughout time and history, incorporated storytelling (and storymaking) into their lives, because it's how we make sense of the dynamic, often complex, situations we find ourselves in. Neil Gaiman, a master story teller, outlines the importance of a good story, and the ability stories have to shape culture and behaviour:

By Neil Gaiman

Stories aren’t books. Books are simply one of the many storage mechanisms in which stories can be kept and, obviously, people are one of the other storage mechanisms. Stories change. The professions, the media that we use to store, record and transmit stories will change. Not long ago the people who stored and transmitted information were stonemasons. Now, not so much. Unless we want the information to last.

As individuals, we are cut off from humanity. As individuals, we are naked, we do not even know which plants will kill us. Without the mass of human knowledge accumulated over millennia to buoy us up, we are in big trouble. With it, we are warm, fed, we have popcorn, we are sitting in comfortable seats and we are capable of arguing with each other about really stupid things on the internet. That's because we have stories, it's because we have information.

In 1984 a man, whose name I don't know how to pronounce, I think it's Thomas Sebeok, wrote a report for the Department of Energy. He was asked to create a report because they had a problem - what to do with nuclear waste repositories. They needed to devise a method of warning future generations not to mine or drill at that site unless they're aware of the other consequences of their actions… and because the stuff that they would be putting in these nuclear waste repositories had a half-life of 10000 years, they needed to figure out ways to get information to last 10000 years. They started by looking at all you can write. The trouble with writing things is that it lasts a certain amount of time, but anyone here who’s actually tried to read Beowulf in the original knows that that only takes you so far. Language changes. Words change meaning. And if language is changing, what about pictographics? What if you put a big skull up? And Thomas pointed out that even a skull means different things in different cultures - some cultures might go “ahh, skull, symbol of warning,” some might go, “symbol of fantastic candy days. This is the place where the good stuff!”.

ISO Radiation Warning Sign

What he actually came up with, he said that the prime recommendation of the Human Interference Task Force of Department of Energy was that information be launched and artificially passed down into the short-term and long-term future, with these supplementary aid of folkloristic devices, in particular a combination of artificially created and nurtured ritual and legend. The most positive aspect of such a procedure is it need not be geographically localised, or tied to any one language or culture. So, the initiated would be steered away from the hazardous site, for reasons other than the scientific knowledge of the possibility of radiation and its implications, essentially the reason would be accumulated superstition to shun a certain area permanently.

A ritual with the legend retold year by year, with presumably slight variation. The actual “truth” would be entrusted exclusively to, what we might call for dramatic emphasis, an ‘atomic priesthood’ - it is a commission of knowledgeable physicists, experts in radiation sickness, anthropologists and whatever additional expertise may be called for in the future. Folklore specialists that they’d consulted say they know of no precedent, nor could they think of a parallel situation, except the well-known but ineffectual curse is associated with the burial sites of some Egyptian Pharaohs, which didn't deter greedy grave robbers from digging for hidden treasure.

“What we can do, I think, is try and create stories that are interesting enough and important enough that our grandchildren might want to tell those stories to their grandchildren. Because that’s the purpose of stories. It’s what they’re for. ”

First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang

Terracotta Warrior

Which is true, up to a point. The first emperor of China died 2000 years ago, and the site of his tomb was lost. Very intentionally lost - he killed anybody who knew where it was. It was a magnificent act of tomb losing. And then one day, in a field in China, somebody unearthed a Terracotta Warrior. And then they found another one. They excavated warriors and archaeologists worked out very quickly where the actual mausoleum had to be. The stories that come down to us 2300 years after the emperor China at died, now became a warning. Remember those lakes of mercury? That stuff is really poisonous. It doesn't even have a half-life, it's just there. As Terry Pratchett once said, “Radiation is 10000 years, arsenic is forever,” and so they didn't immediately start digging, instead they checked, confirmed the presence of incredibly high quantities of mercury and have been figuring out what to do ever since. And when they figure out how to get in there without dying, they will start excavating.

The Long Now, and the clock of The Long Now is about planning for the long term, and thinking in the long term, in a world in which people appear to be thinking in the shorter and shorter term, not even necessarily at this point about things that will take them to the end of their lifetime, which at least at one point you would have thought, “well, you know, I'll be dead before that's a problem,” looking around now, the mess we’re making of things on his planet. You wanna go to people and say, “you know actually, you will be. You will still be around. We could run out of water, you'll be here, having to figure out what to do with no water. What to do when the oceans are screwed up. What to do when Twitter finally becomes sentient.

Tom Sebeok concluded that you couldn’t actually create a story that would last 10000 years, you could only create a story that would last a 3 Generations - for ourselves, for our children, for their children. But what we can do, I think, is try and create stories that are interesting enough and important enough that our grandchildren might want to tell those stories to their grandchildren. Because that's the purpose of stories. It's what they’re for. They make life worth living and, sometimes, they keep us alive

Neil Gaiman has told stories in every medium—graphic novels (The Sandman), novels (The Ocean at the End of the Lane; American Gods), short stories (Trigger Warning), children’s books (The Graveyard Book), television (Dr Who), and the occasional song (“I Google You”)

This is an extract from a 2015 talk delivered by Neil Gaiman entitled "How Stories Last" delivered for the Long Now Foundation, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

A tangible demonstration of the power of storytelling: The significant objects experiment

The Significant Objects experiment is a tangible demonstration of the power of storytelling in sales and marketing. Journalist Rob Walker purchased low value objects, for on average $1.25 and had great creative writers invent stories about them. He then posted the articles on e-Bay to see if the invented story enhanced the value of the object based on what price it achieves on auction.

It did.

The Significant Objects experiment is a tangible demonstration of the power of storytelling in sales and marketing.

Journalist Rob Walker purchased low value objects, for on average $1.25 and had great creative writers invent stories about them. He then posted the articles on e-Bay to see if the invented story enhanced the value of the object based on what price it achieves on auction.

It did.

An old pepper shaker was bought for 99 cents, and sold for $28.00. A butterfly embossed cigarette case was bought for 10 cents, and sold for $33.77. A horse bust was bought for 99c and sold for $62.95

All in all, 100 pieces were cost $128.74, and were sold for $3612.51 - a whopping 2780% increase in value.

That's story power.

This apple was bought for $1.00, and sold for $102.50 with a story.

Cultural Cartography: How Buzzfeed organises their content

Last year, Buzzfeed started a project to formally categorize their content. They called it "cultural cartography." It formalized an informal practice that they've had for a really long time: don't just think about the subject matter; think also about, and in fact, primarily about, the job that your content is doing for the reader or the viewer.

By Dao Nguyen

Last year, some BuzzFeed employees were scheming to prank their boss, Ze Frank, on his birthday. They decided to put a family of baby goats in his office.

BuzzFeed had recently signed on to the Facebook Live experiment, and so naturally, we decided to livestream the whole event on the internet to capture the moment when Ze would walk in and discover livestock in his office. We thought the whole thing would last maybe 10 minutes, and a few hundred company employees would log in for the inside joke. But what happened? They kept on getting delayed: he went to get a drink, he was called to a meeting, the meeting ran long, he went to the bathroom. More and more people started logging in to watch the goats. By the time Ze walked in more than 30 minutes later, 90,000 viewers were watching the livestream.

Now, our team had a lot of discussion about this video and why it was so successful. It wasn't the biggest live video that we had done to date (the biggest one that we had done involved a fountain of cheese). But it performed so much better than we had expected. What was it about the goats in the office that we didn't anticipate?

Now, a reasonable person could have any number of hypotheses. Maybe people love baby animals. Maybe people love office pranks. Maybe people love stories about their bosses or birthday surprises. But our team wasn't really thinking about what the video was about. We were thinking about what the people watching the video were thinking and feeling. We read some of the 82,000 comments that were made during the video, and we hypothesized that they were excited because they were participating in the shared anticipation of something that was about to happen. They were part of a community, just for an instant, and it made them happy.

So we decided that we needed to test this hypothesis. What could we do to test this very same thing? The following week, armed with the additional knowledge that food videos are very popular, we dressed two people in hazmat suits and wrapped rubber bands around a watermelon until it exploded.

Eight hundred thousand people watched the 690th rubber band explode the watermelon, marking it as the biggest Facebook Live event to date.

The question I get most frequently is: How do you make something go viral? The question itself is misplaced; it's not about the something. It's about what the people doing the something - reading or watching - what are they thinking?

Now, most media companies, when they think about metadata, they think about subjects or formats. It's about goats, it's about office pranks, it's about food, it's a list or a video or a quiz, it's 2,000 words long, it's 15 minutes long, it has 23 embedded tweets or 15 images. Now, that kind of metadata is mildly interesting, but it doesn't actually get at what really matters. What if, instead of tagging what articles or videos are about, what if we asked: How is it helping our users do a real job in their lives?

The Cultural Cartography of Social Content

Last year, we started a project to formally categorize our content in this way. We called it, "cultural cartography." It formalized an informal practice that we've had for a really long time: don't just think about the subject matter; think also about, and in fact, primarily about, the job that your content is doing for the reader or the viewer.

Let me show you the map that we have today. Each bubble is a specific job, and each group of bubbles in a specific color are related jobs.

First up: humour. "Makes me laugh." There are so many ways to make somebody laugh. You can be laughing at someone, you could laugh at specific internet humour, you could be laughing at some good, clean, inoffensive dad jokes.

"This is me." Identity. People are increasingly using media to explain, "This is who I am. This is my upbringing, this is my culture, this is my fandom, this is my guilty pleasure, and this is how I laugh about myself."

The "Helps me Connect with Another Person" category

"Helps me connect with another person." This is one of the greatest gifts of the internet. It's amazing when you find a piece of media that precisely describes your bond with someone. The green bubbles make up the group of jobs that help me do something -- 'helps me settle an argument'; 'helps me learn something about myself or another person'; or 'helps me explain my story'.

The orange bubbles are the group of jobs that makes me feel something -- makes me curious or sad or restores my faith in humanity.

“If we can capture in data what really matters to you, and if we can understand the role that our work plays in your actual life, the better content we can create for you, and the better that we can reach you”

Many media companies and creators do put themselves in their audiences' shoes. But in the age of social media, we can go much farther. People are connected to each other on Facebook, on Twitter, and they're increasingly using media to have a conversation and to talk to each other. If we can be a part of establishing a deeper connection between two people, then we will have done a real job for these people.

Let me give you an example of how this plays out. This is one of my favorite lists: "32 Memes You Should Send Your Sister Immediately". It has things that are relatable, like: "When you're going through your sister's stuff, and you hear her coming up the stairs." Absolutely, I've done that. "Watching your sister get in trouble for something that you did and blamed on her." Yes, I've done that as well. This list got three million views. Why is that? Because it did, very well, several jobs: "This is us." "Connect with family." "Makes me laugh."

Now, we can even apply this framework to recipes and food. A recipe's normal job is to tell you what to make for dinner or for lunch. And this is how you would normally brainstorm for a recipe: you figure out what ingredients you want to use, what recipe that makes, and then maybe you slap a job on at the end to sell it. But what if we flipped it around and thought about the job first? One brainstorming session involved the job of bonding. So, could we make a recipe that brought people together? This is not a normal brainstorming process at a food publisher. So we know that people like to bake together, and we know that people like to do challenges together, so we decided to come up with a recipe that involved those two things, and we challenged ourselves: Could we get people to say, "Hey, BFF, let's see if we can do this together"? The resulting video was the "Fudgiest Brownies Ever" video. It was enormously successful in every metric possible -- 50 million views. And people said the exact things that we were going after: "Hey, Colette, we need to make these, are you up for a challenge?" "Game on." It did the job that it set out to do, which was to bring people together over baking and chocolate.

Metadata and Storymaking

I'm really excited about the potential for this project. When we talk about this framework with our content creators, they instantly get it, no matter what beat they cover, what country they’re in, or what language they speak. So cultural cartography has helped us massively scale our workforce training. When we talk about this project and this framework with advertisers and brands, they also instantly get it, because advertisers, more often than media companies, understand how important it is to understand the job that their products are doing for customers.

But the reason I'm the most excited about this project is because it changes the relationship between media and data. Most media companies think of media as "mine." How many fans do I have? How many followers have I gained? How many views have I gotten? How many unique IDs do I have in my data warehouse? But that misses the true value of data, which is that it's yours. If we can capture in data what really matters to you, and if we can understand more the role that our work plays in your actual life, the better content we can create for you, and the better that we can reach you.

Who are you? How did you get there? Where are you going? What do you care about? What can you teach us? That's cultural cartography.

As a Media Analytics Expert and Publisher of BuzzFeed, Dao Nguyen thinks about how media spreads online and the technology and data that publishers can use to understand why. Dao Nguyen is the Publisher of BuzzFeed, a reinvention of the traditional title in which she oversees the company’s tech, product, data and publishing platform, as well as ad product, pricing, and distribution. Nguyen joined BuzzFeed in 2012 and has been instrumental in its rapid growth as the largest independent digital media company in the world

This is an extract from a 2017 talk delivered by Dao Nguyen entitled "What Makes Something Go Viral?" delivered at TedNYC, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

The human insights missing from Big Data

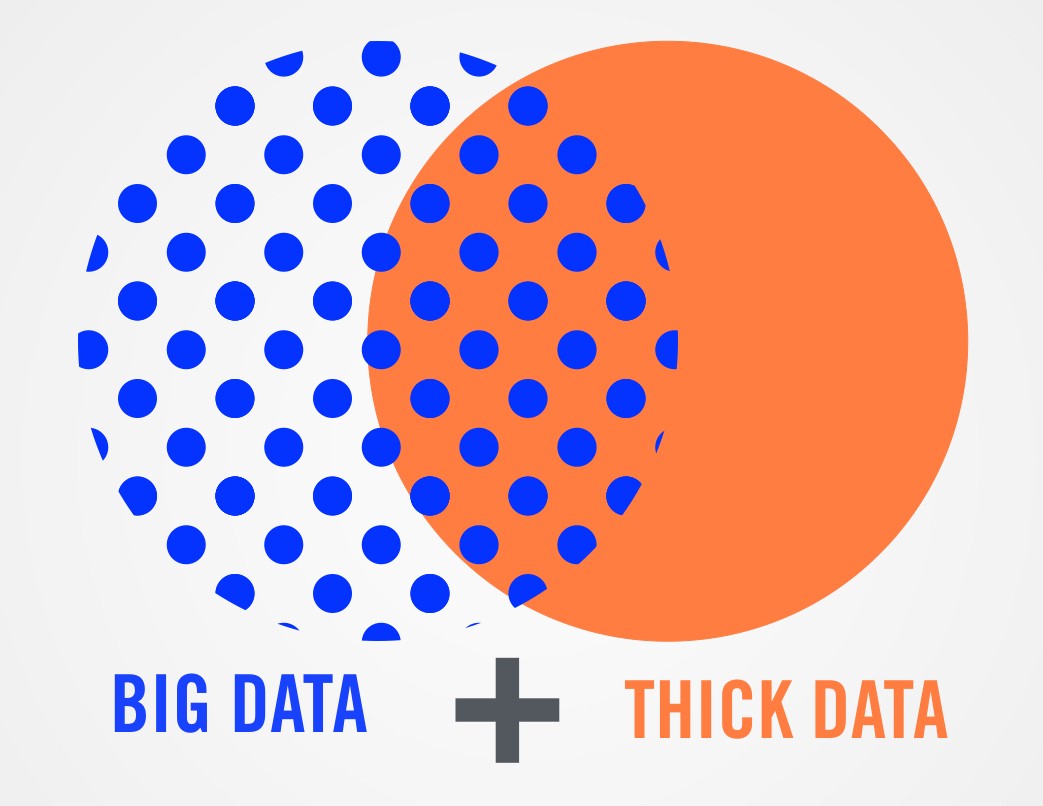

Thick data grounds our business questions in human questions, and that's why integrating big and thick data forms a more complete picture. Big data is able to offer insights at scale and leverage the best of machine intelligence, whereas thick data can help us rescue the context loss that comes from making big data usable, and leverage the best of human intelligence. And when you actually integrate the two, that's when things get really fun, because then you're no longer just working with data you've already collected. You get to also work with data that hasn't been collected. You get to ask questions about why: Why is this happening?

By Tricia Wang

In ancient Greece, when anyone from slaves to soldiers, poets and politicians, needed to make a big decision on life's most important questions, like, "Should I get married?" or "Should we embark on this voyage?" or "Should our army advance into this territory?" they all consulted the oracle.

So this is how it worked: you would bring her a question and you would get on your knees, and then she would go into this trance. It would take a couple of days, and then eventually she would come out of it, giving you her predictions as your answer.

From the oracle bones of ancient China to ancient Greece to Mayan calendars, people have craved for prophecy in order to find out what's going to happen next. And that's because we all want to make the right decision. We don't want to miss something. The future is scary, so it's much nicer knowing that we can make a decision with some assurance of the outcome.

Photo credit: Merrill College of Journalism Press Releases on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC

Well, we have a new oracle, and it's name is big data, or we call it "Watson" or "deep learning" or "neural net." And these are the kinds of questions we ask of our oracle now, like, "What's the most efficient way to ship these phones from China to Sweden?" Or, "What are the odds of my child being born with a genetic disorder?" Or, "What are the sales volume we can predict for this product?"

Now, despite the size of this industry, the returns are surprisingly low. Investing in big data is easy, but using it is hard. Over 73 percent of big data projects aren't even profitable, and I have executives coming up to me saying, "We're experiencing the same thing. We invested in some big data system, and our employees aren't making better decisions. And they're certainly not coming up with more breakthrough ideas."

This is all really interesting to me, because I'm a technology ethnographer. I study and I advise companies on the patterns of how people use technology, and one of my interest areas is data. So, why is having more data not helping us make better decisions, especially for companies who have all these resources to invest in these big data systems? Why isn't it getting any easier for them?

I've witnessed the struggle firsthand. In 2009, I started a research position with Nokia. And at the time, Nokia was one of the largest cell phone companies in the world, dominating emerging markets like China, Mexico and India -- all places where I had done a lot of research on how low-income people use technology. And I spent a lot of extra time in China getting to know the informal economy. I did things like working as a street vendor selling dumplings to construction workers. Or I did fieldwork, spending nights and days in internet cafés, hanging out with Chinese youth, so I could understand how they were using games and mobile phones and using it between moving from the rural areas to the cities.

Big Data Didn't Predict the Mass Adoption of the SmartPhone in China

I've witnessed the struggle firsthand. In 2009, I started a research position with Nokia. And at the time, Nokia was one of the largest cell phone companies in the world, dominating emerging markets like China, Mexico and India -- all places where I had done a lot of research on how low-income people use technology. And I spent a lot of extra time in China getting to know the informal economy. I did things like working as a street vendor selling dumplings to construction workers. Or I did fieldwork, spending nights and days in internet cafés, hanging out with Chinese youth, so I could understand how they were using games and mobile phones and using it between moving from the rural areas to the cities.

“So why is having more data not helping us make better decisions, especially for companies who have all these resources to invest in big data systems?”

Through all of this qualitative evidence that I was gathering, I was starting to see so clearly that a big change was about to happen among low-income Chinese people. Even though they were surrounded by advertisements for luxury products like fancy toilets -- who wouldn't want one? -- and apartments and cars, through my conversations with them, I found out that the ads the actually enticed them the most were the ones for iPhones, promising them this entry into this high-tech life. And even when I was living with them in urban slums, I saw people investing over half of their monthly income into buying a phone, and increasingly, they were "shanzhai," which are affordable knock-offs of iPhones and other brands. They're very usable. Does the job.

And after years of living with migrants and working with them and just really doing everything that they were doing, I started piecing all these data points together -- from the things that seem random, like me selling dumplings, to the things that were more obvious, like tracking how much they were spending on their cell phone bills. And I was able to create this much more holistic picture of what was happening. And that's when I started to realize that even the poorest in China would want a smartphone, and that they would do almost anything to get their hands on one.

You have to keep in mind, iPhones had just come out, it was 2009, so this was, like, eight years ago, and Androids had just started looking like iPhones. And a lot of very smart and realistic people said, "Those smartphones -- that's just a fad. Who wants to carry around these heavy things where batteries drain quickly and they break every time you drop them?" But I had a lot of data, and I was very confident about my insights, so I was very excited to share them with Nokia.

But Nokia was not convinced, because it wasn't big data. They said, "We have millions of data points, and we don't see any indicators of anyone wanting to buy a smartphone, and your data set of 100, as diverse as it is, is too weak for us to even take seriously." And I said, "Nokia, you're right. Of course you wouldn't see this, because you're sending out surveys assuming that people don't know what a smartphone is, so of course you're not going to get any data back about people wanting to buy a smartphone in two years. Your surveys, your methods have been designed to optimize an existing business model, and I'm looking at these emergent human dynamics that haven't happened yet. We're looking outside of market dynamics so that we can get ahead of it." Well, you know what happened to Nokia? Their business fell off a cliff. This -- this is the cost of missing something. It was unfathomable.

But Nokia's not alone. I see organizations throwing out data all the time because it didn't come from a quant model or it doesn't fit in one. But it's not big data's fault. It's the way we use big data; it's our responsibility. Big data's reputation for success comes from quantifying very specific environments, like electricity power grids or delivery logistics or genetic code, when we're quantifying in systems that are more or less contained.

But not all systems are as neatly contained. When you're quantifying and systems are more dynamic, especially systems that involve human beings, forces are complex and unpredictable, and these are things that we don't know how to model so well. Once you predict something about human behavior, new factors emerge, because conditions are constantly changing. That's why it's a never-ending cycle. You think you know something, and then something unknown enters the picture. And that's why just relying on big data alone increases the chance that we'll miss something, while giving us this illusion that we already know everything.

And what makes it really hard to see this paradox and even wrap our brains around it is that we have this thing that I call the quantification bias, which is the unconscious belief of valuing the measurable over the immeasurable. And we often experience this at our work. This is a very appealing message, because there's nothing wrong with quantifying; it's actually very satisfying. I get a great sense of comfort from looking at an Excel spreadsheet, even very simple ones.

image: Mark Smiciklas at Intersection Consulting

But the problem is that quantifying is addictive. And when we forget that and when we don't have something to kind of keep that in check, it's very easy to just throw out data because it can't be expressed as a numerical value. It's very easy just to slip into silver-bullet thinking, as if some simple solution existed. Because this is a great moment of danger for any organization, because oftentimes, the future we need to predict -- it isn't in that haystack, but it's that tornado that's bearing down on us outside of the barn. There is no greater risk than being blind to the unknown. It can cause you to make the wrong decisions. It can cause you to miss something big.

But we don't have to go down this path. It turns out that the oracle of ancient Greece holds the secret key that shows us the path forward. Now, recent geological research has shown that the Temple of Apollo, where the most famous oracle sat, was actually built over two earthquake faults. And these faults would release these petrochemical fumes from underneath the Earth's crust, and the oracle literally sat right above these faults, inhaling enormous amounts of ethylene gas, these fissures.

It's all true, and that's what made her babble and hallucinate and go into this trance-like state. She was high as a kite!

The Oracle by Camillo Miola

So how did anyone -- How did anyone get any useful advice out of her in this state? Well, you see those people surrounding the oracle? You see those people holding her up, and you see that guy on your left-hand side holding the orange notebook? Well, those were the temple guides, and they worked hand in hand with the oracle. When inquisitors would come and get on their knees, that's when the temple guides would get to work, because after they asked her questions, they would observe their emotional state, and then they would ask them follow-up questions, like, "Why do you want to know this prophecy? Who are you? What are you going to do with this information?" And then the temple guides would take this more ethnographic, this more qualitative information, and interpret the oracle's babblings.

So the oracle didn't stand alone, and neither should our big data systems.

Now to be clear, I'm not saying that big data systems are huffing ethylene gas, or that they're even giving invalid predictions. The total opposite. But what I am saying is that in the same way that the oracle needed her temple guides, our big data systems need them, too. They need people like ethnographers and user researchers who can gather what I call thick data. This is precious data from humans, like stories, emotions and interactions that cannot be quantified. It's the kind of data that I collected for Nokia that comes in in the form of a very small sample size, but delivers incredible depth of meaning.

And what makes it so thick and meaty is the experience of understanding the human narrative. And that's what helps to see what's missing in our models. Thick data grounds our business questions in human questions, and that's why integrating big and thick data forms a more complete picture. Big data is able to offer insights at scale and leverage the best of machine intelligence, whereas thick data can help us rescue the context loss that comes from making big data usable, and leverage the best of human intelligence. And when you actually integrate the two, that's when things get really fun, because then you're no longer just working with data you've already collected. You get to also work with data that hasn't been collected. You get to ask questions about why: Why is this happening?

“Thick data grounds our business questions in human questions, and that’s why integrating big and thick data forms a more complete picture”

Now, when Netflix did this, they unlocked a whole new way to transform their business. Netflix is known for their really great recommendation algorithm, and they had this $1 million prize for anyone who could improve it. And there were winners. But Netflix discovered the improvements were only incremental. So to really find out what was going on, they hired an ethnographer, Grant McCracken, to gather thick data insights. And what he discovered was something that they hadn't seen initially in the quantitative data. He discovered that people loved to binge-watch. In fact, people didn't even feel guilty about it. They enjoyed it.

So Netflix was like, "Oh. This is a new insight." So they went to their data science team, and they were able to scale this big data insight in with their quantitative data. And once they verified it and validated it, Netflix decided to do something very simple but impactful. They said, "instead of offering the same show from different genres or more of the different shows from similar users, we'll just offer more of the same show. We'll make it easier for you to binge-watch." And they didn't stop there. They did all these things to redesign their entire viewer experience, to really encourage binge-watching. It's why people and friends disappear for whole weekends at a time, catching up on shows like "Master of None." By integrating big data and thick data, they not only improved their business, but they transformed how we consume media. And now their stocks are projected to double in the next few years.

But this isn't just about watching more videos or selling more smartphones. For some, integrating thick data insights into the algorithm could mean life or death, especially for the marginalized. All around the country, police departments are using big data for predictive policing, to set bond amounts and sentencing recommendations in ways that reinforce existing biases. NSA's Skynet machine learning algorithm has possibly aided in the deaths of thousands of civilians in Pakistan from misreading cellular device metadata. As all of our lives become more automated, from automobiles to health insurance or to employment, it is likely that all of us will be impacted by the quantification bias.

Now, the good news is that we've come a long way from huffing ethylene gas to make predictions. We have better tools, so let's just use them better. Let's integrate the big data with the thick data. Let's bring our temple guides with the oracles, and whether this work happens in companies or nonprofits or government or even in the software, all of it matters, because that means we're collectively committed to making better data, better algorithms, better outputs and better decisions. This is how we'll avoid missing that something.

With astronaut eyes and ethnographer curiosity, Tricia Wang helps corporations grow by discovering the unknown about their customers. She has taught global organizations how to identify new customers and markets hidden behind their data, amplified IDEO's design thinking practice as an expert-in-residence, researched the social evolution of the Chinese internet, and written about the "elastic self," an emergent form of interaction in a virtual world. Wang is the co-founder of Sudden Compass, a consulting firm that helps companies unlock new growth opportunities by putting customer obsession into practice.

This is an extract from a 2016 talk delivered by Tricia Wang entitled "The Human Insights Missing from Big Data" delivered at TedxCambridge, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License