The Taste Gap

So many of us get into social media because we admire the work of creatives in the field, the brilliant memes, the awe inspiring videos, the perspective altering tweets. But there’s a gap when we start. What we produce doesn’t live up to our own expectations. Ira Glass’ insights on the creative process remind us to push through the frustrating beginnings of creative work, and keep working until what we produce reflects our good taste

Recombiner

So many of us get into social media because we admire the work of creatives in the field, the brilliant memes, the awe inspiring videos, the perspective altering tweets. But there’s a gap when we start. What we produce doesn’t live up to our own expectations. Our taste exceeds our ability.

“A lot of people never get past this phase," notes Ira Glass because they succumb to the disappointment of producing work that doesn’t match up to the sky-high expectations set by their taste. Every creative has at least once considered packing it in and pursuing the most un-creative career trajectory possible, simply to avoid the heartbreak of knowing their work doesn’t quite cut it.

by Recombiner

“In the beginning, and for a while afterwards we know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have,” says Glass. “We all go through this. And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know it’s normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. It’s gonna take a while. It’s normal to take a while. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.”

It’s tempting sometimes just to stop trying to be excellent, to start filling the content calendar with “content” rather than striving for the breakthrough executions that get noticed and engaged with. So even as you cringe at your first attempts, recognise the taste gap. Then get back to writing your headline 25 times until it’s as catchy as it can be.

And maybe - if you work damn hard at it - your ability will catch up with your taste.

Ira Glass on the Creative Process:

Related Skill

Book a course related to this article:

The simple trick to finding the most connected and influential people in a social network

We're all embedded in vast social networks of friends, family, co-workers and more. Nicholas Christakis tracks how a wide variety of traits can spread from person to person, showing how your location in the network might impact your life in ways you don't even know. Christakis highlights how new forms of data collection allow us to locate the central people within a network and ultimately "use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being."

We're all embedded in vast social networks of friends, family, co-workers and more. Nicholas Christakis tracks how a wide variety of traits -- from happiness to obesity -- can spread from person to person, showing how your location in the network might impact your life in ways you don't even know. Christakis highlights how new forms of data collection allow us to locate the central people within a network and ultimately "use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being."

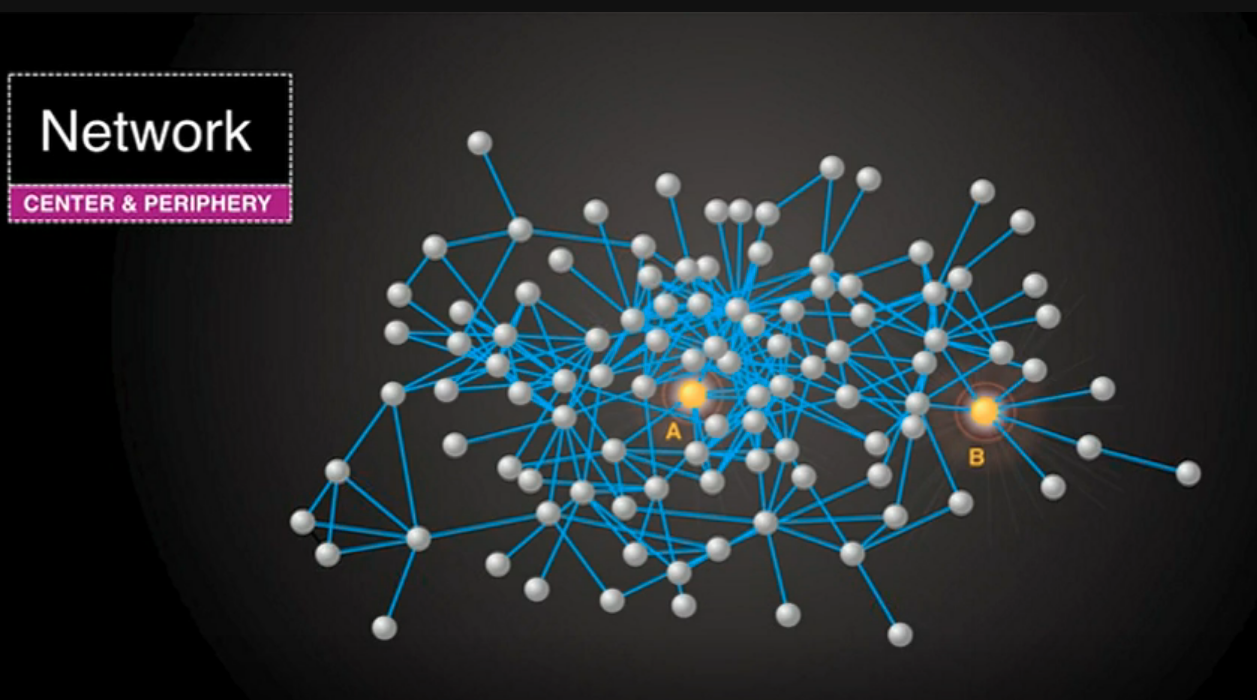

For the last 10 years, I've been spending my time trying to figure out how and why human beings assemble themselves into social networks. And the kind of social network I'm talking about is not the recent online variety, but rather, the kind of social networks that human beings have been assembling for hundreds of thousands of years, ever since we emerged from the African savannah. So, I form friendships and co-worker and sibling and relative relationships with other people who in turn have similar relationships with other people. And this spreads on out endlessly into a distance. And you get a network that looks like this. Every dot is a person. Every line between them is a relationship between two people -- different kinds of relationships. And you can get this vast fabric of humanity, in which we're all embedded.

My colleague, James Fowler and I have been studying for quite sometime what are the mathematical, social, biological and psychological rules that govern how these networks are assembled and what are the similar rules that govern how they operate, how they affect our lives. But recently, we've been wondering whether it might be possible to take advantage of this insight, to actually find ways to improve the world, to do something better, to actually fix things, not just understand things.

So one of the first things we thought we would tackle would be how we go about predicting epidemics.

And the current state of the art in predicting an epidemic -- if you're the CDC or some other national body -- is to sit in the middle and collect data from physicians and laboratories in the field that report the prevalence or the incidence of certain conditions. These data are fed into a central repository, with some delay. And if everything goes smoothly, one to two weeks from now you'll know where the epidemic was today. And actually, about a year or so ago, there was this promulgation of the idea of Google Flu Trends, with respect to the flu, where by looking at people's searching behavior today, we could know what the status of the epidemic was today, what's the prevalence of the epidemic today.

But what I'd like to show you is a means by which we might get not just rapid warning about an epidemic, but also actually early detection of an epidemic. And, in fact, this idea can be used not just to predict epidemics of germs, but also to predict epidemics of all sorts of kinds. For example, anything that spreads by a form of social contagion could be understood in this way, from abstract ideas on the left like patriotism, or altruism, or religion to practices like dieting behavior, or book purchasing, or drinking, or products that people might buy, purchases of electronic goods, anything in which there's kind of an interpersonal spread.

A kind of a diffusion of innovation could be understood and predicted by the following mechanism.

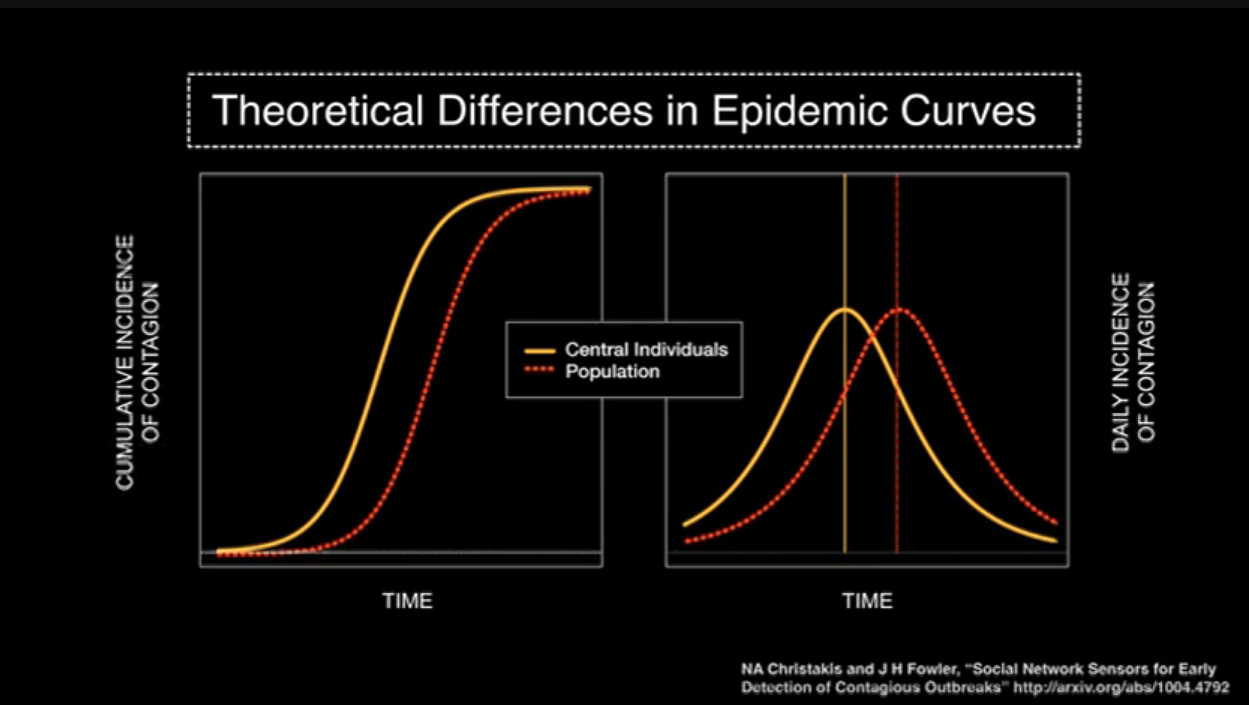

As you probably know, the classic way of thinking about this is the diffusion-of-innovation, or the adoption curve. So here on the Y-axis, we have the percent of the people affected, and on the X-axis, we have time. And at the very beginning, not too many people are affected, and you get this classic sigmoidal, or S-shaped, curve. And the reason for this shape is that at the very beginning, let's say one or two people are infected, or affected by the thing and then they affect, or infect, two people, who in turn affect four, eight, 16 and so forth, and you get the epidemic growth phase of the curve. And eventually, you saturate the population. There are fewer and fewer people who are still available that you might infect, and then you get the plateau of the curve, and you get this classic sigmoidal curve. And this holds for germs, ideas, product adoption, behaviors, and the like.

But things don't just diffuse in human populations at random. They actually diffuse through networks. Because we live our lives in networks, and these networks have a particular kind of a structure.

Now if you look at a network like this - this is 105 people. The dots are the people, and the lines represent friendship relationships. You might see that people occupy different locations within the network. And there are different kinds of relationships between the people. You could have friendship relationships, sibling relationships, spousal relationships, co-worker relationships, neighbor relationships and the like. And different sorts of things spread across different sorts of ties. For instance, sexually transmitted diseases will spread across sexual ties. Or, for instance, people's smoking behavior might be influenced by their friends. Or their altruistic or their charitable giving behavior might be influenced by their coworkers, or by their neighbors.

But not all positions in the network are the same.

If you look at this, you might immediately grasp that different people have different numbers of connections. Some people have one connection, some have two, some have six, some have 10 connections. This is called the "degree" of a node, or the number of connections that a node has.

But in addition, there's something else.

If you look at nodes A and B, they both have six connections. But if you can see this image [of the network] from a bird's eye view, you can appreciate that there's something very different about nodes A and B.

So, let me ask you this -- who would you rather be if a deadly germ was spreading through the network, A or B? B, it's obvious. B is located on the edge of the network. Now, who would you rather be if a juicy piece of gossip were spreading through the network? A. A is going to be more likely to get the thing that's spreading and to get it sooner by virtue of their structural location within the network. A, in fact, is more central, and this can be formalised mathematically.

So, if we want to track something that was spreading through a network, what we ideally would like to do is to set up sensors on the central individuals within the network, including node A, monitor those people that are right there in the middle of the network, and somehow get an early detection of whatever it is that is spreading through the network.

If you saw them contract a germ or a piece of information, you would know that, soon enough, everybody was about to contract this germ or this piece of information. If you could do that, what you would see is something like this. On the left-hand panel, again, we have the S-shaped curve of adoption. In the dotted red line, we show what the adoption would be in the random people, and in the left-hand line, shifted to the left, we show what the adoption would be in the central individuals within the network. On the Y-axis is the cumulative instances of contagion, and on the X-axis is the time. And on the right-hand side, we show the same data, but here with daily incidence. But shifted to the left is what's occurring in the central individuals. And this difference in time between the two is the early detection, the early warning we can get, about an impending epidemic in the human population.

The problem, however, is that mapping human social networks is not always possible. It can be expensive, not feasible, unethical, or, frankly, just not possible to do such a thing.

So, how can we figure out who the central people are in a network without actually mapping the network?

What we came up with was an idea to exploit an old fact about social networks, which goes like this: Do you know that your friends have more friends than you do? This is known as the friendship paradox. Imagine a very popular person in the social network -- like a party host who has hundreds of friends -- and a misanthrope who has just one friend, and you pick someone at random from the population; they were much more likely to know the party host. And if they nominate the party host as their friend, that party host has a hundred friends, therefore, has more friends than they do. And this, in essence, is what's known as the friendship paradox. The friends of randomly chosen people have higher degree, and are more central than the random people themselves.

And you can get an intuitive appreciation for this if you imagine just the people at the perimeter of the network. If you pick this person, the only friend they have to nominate is this person who, by construction, must have at least two and typically more friends. And that happens at every peripheral node. In fact, it happens throughout the network you move in -- when a random person nominates a friend of theirs, you move closer to the center of the network. So, we thought we would exploit this idea in order to study whether we could predict phenomena within networks. Because now, with this idea we can take a random sample of people, have them nominate their friends, those friends would be more central, and we could do this without having to map the network.

And we tested this idea with an outbreak of H1N1 flu at Harvard College in the fall and winter of 2009:

We took 1,300 randomly selected undergraduates, we had them nominate their friends, and we followed both the random students and their friends daily in time to see whether or not they had the flu epidemic. And we did this passively by looking at whether or not they'd gone to university health services. We also had them [actively] email us a couple of times a week.

Exactly what we predicted happened.

The random group is in the red line. The epidemic in the friends group has shifted to the left, over here. And the difference in the two is 16 days. By monitoring the friends group, we could get 16 days advance warning of an impending epidemic in this human population.

I should say that how far advanced a notice one might get about something depends on a host of factors. It could depend on the nature of the pathogen -- different pathogens, using this technique, you'd get different warning -- or other phenomena that are spreading, or frankly, on the structure of the human network. In our case, although it wasn't necessary, we could also actually map the network of the students.

As I've been suggesting, this method is not restricted to germs, but actually to anything that spreads in populations. Information spreads in populations, norms can spread in populations, behaviors can spread in populations. And by behaviors, I can mean things like criminal behavior, or voting behavior, or health care behavior, like smoking, or vaccination, or product adoption, or other kinds of behaviors that relate to interpersonal influence. If I'm likely to do something that affects others around me, this technique can get early warning or early detection about the adoption within the population. The key thing is that for it to work, there has to be interpersonal influence. It cannot be because of some broadcast mechanism affecting everyone uniformly.

Similar ideas can be used, for instance, to target distribution of things like bed nets in the developing world. If we could understand the structure of networks in villages, we could target to whom to give the interventions to foster these kinds of spreads. Or, frankly, for advertising with all kinds of products. If we could understand how to target, it could affect the efficiency of what we're trying to achieve. And in fact, we can use data from all kinds of sources nowadays [to do this].

This is a map of eight million phone users in a European country. Every dot is a person, and every line represents a volume of calls between the people. And we can use such data, that's being passively obtained, to map these whole countries and understand who is located where within the network. Without actually having to query them at all, we can get this kind of a structural insight. Other sources of information are available about such features, from email interactions, online interactions, online social networks and so forth. In fact, we are in the era of what I would call "massive-passive" data collection efforts. They're all kinds of ways we can use massively collected data to create sensor networks to follow the population, understand what's happening in the population, and intervene in the population for the better. Because these new technologies tell us not just who is talking to whom, but where everyone is, and what they're thinking based on what they're uploading on the Internet, and what they're buying based on their purchases. All this administrative data can be pulled together and processed to understand human behavior in a way we never could before.

There are three ways that these massive-passive data can be used.

Fully passive, where we don't actually intervene in the population in any way.

Quasi-active, like the flu example, where we get some people to nominate their friends and then passively monitor their friends -- do they have the flu, or not? -- and then get warning.

Fully active where people might globally participate in wikis, or photographing, or monitoring elections, and upload information in a way that allows us to pool information in order to understand social processes and social phenomena.

In fact, the availability of these data, heralds a kind of new era of what I and others would like to call "computational social science." Now we have access to these kinds of data that allow us to understand social processes and social phenomena in an entirely new way that was never before possible. With this science, we can understand how exactly the whole comes to be greater than the sum of its parts. And actually, we can use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is an internist and social scientist who conducts research on social factors that affect health, health care, and longevity. He is Professor of Medical Sociology in the Department of Health Care Policy at Harvard Medical School; Professor of Medicine in the Department of Medicine at Harvard Medical School; Professor of Sociology in the Department of Sociology in the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences; and an Attending Physician (with an emphasis on palliative medicine) in the Department of Medicine at the Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

This is an extract from a 2010 talk delivered by Nicholas Christakis entitled "How social networks predict epidemics" delivered at TED@Cannes, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Related Skill

Book a class related to this article:

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is busy loading, please upgrade your infrastructure ████░░░░░░░░░ 33%

We are realising the limits of virtualisation. We still need to grow real food, wear real clothes, move real things around in the real world. And the way we do that hasn't changed fundamentally in the past 50 years. The internet has given us a new operating system, but it’s time to upgrade our hardware.

by Dave Duarte

Apple, Google, Tencent, Microsoft, Samsung. The leaders of the digital revolution. They've displaced the bastions of the pre-digital economy for the top spots in the most valuable companies list, and virtualised the way we shop, play, bank, and more.

All this, and yet we are realising the limits of virtualisation. We still need to grow real food, wear real clothes, move real things around in the real world. And the way we do that hasn't changed fundamentally in the past 50 years. We're still dependent on the oil-powered logistics network of the 20th century. In other words, we have a new operating system running on old hardware.

The industries that can be easily virtualised have streaked ahead, leaving the old economy flailing. Youth unemployment is on the rise, GDP around the world is slowing, and tensions are escalating as demand for scarce resources increases faster than our current production capacity. This is why we are seeing the rise of populism again, as people become desperate to vote for leaders who promise them radical economic transformation.

According the renowned economist Jeremy Rifkin, we will only experience radical economic transformation when we have a convergence of next-generation infrastructure in three fields: 1. Communications, 2. Energy, and 3. Transport.

In other words, now is not the time to get complacent about change. It is upgrade or die.

The Three Industrial Revolutions to Date

Let's go back in history for a moment to illustrate.

In the First Industrial Revolution of the 19th Century you have the printing press in Communications (it's been around for a couple of centuries already); but then in Energy, you have steam power so you can power this printing press to produce greater volumes of literature cheaper and faster; and then in Transportation you have locomotion, which helps transport that literature globally.

Innovation booms. And a sustainable shift happens as print technology is introduced into public schools, allowing for a workforce that was more literate than ever before, and ultimately equipped to manage the ever-growing coal and rail infrastructure.

“We couldn’t have done it with an illiterate workforce,” Rifkin states, highlighting just how important this convergence was for the success of the First industrial Revolution.

Moving to the Second Industrial Revolution, things speed up even more. This is all about bringing the advanced technologies of the day to more people.

In Communications we see the telephone network - people can coordinate production and trade across vast distances in real time. A game changer!

In Energy we witness the centralisation of electricity, thanks to the creation of an energy distribution grid. Startup costs plummet, factories pop up everywhere.

And of course, in Transport, the factory-made automobile changes everything.

Combine these major breakthroughs with radio and television and we see suburban society mass consumer culture, and an unprecedented rise in living standards. Major level up.

The third industrial revolution has transformed communications, media, and finance. This thanks largely to the upgrade in Communications infrastructure. And yet we haven't seen the same step change in the other two major infrastructures: transport and energy.

The auto-oil industrial complex of the 20th century is on its last legs. Fossil fuels are increasingly expensive and environmentally unsustainable. Expensive Infrastructure investments in coal, oil and gas are looking less like sure bets, and so the old infrastructure is crumbling.

You can have market reforms, labour reforms, fiscal reforms, new kinds of incentives for entrepreneurs, but as long as you are building on this old system, aggregate efficiency is going to remain stuck.

Time for a Systems Upgrade

Using Rifkin's model, it's plain that the key to unlocking the Fourth Industrial Revolution is in not just Renewable Energy, and Electric Vehicles, but in the infrastructure that enables those networks to function in a decentralised way.

Let's paint the picture: You have renewable energy that is already cheaper per MW than fossil fuels. You have electric vehicles that can be powered by this essentially limitless energy source; and you can connect these systems to the internet, which allows for remote coordination, automation, and machine learning to make the whole system much more efficient.

That efficiency will be translated in terms of much lower cost prices for everything - from food staples to clothing and more. This means things are more affordable for more people, and the world becomes more inclusive (again - just like previous industrial revolutions).

What about the Jobs?

This global network of internet connected cities, vehicles, buildings, and objects is going to require a LOT of human work to be built. We are talking new factories, new service businesses, plumbers installing sensors, electricians upgrading homes and offices.

"We are in a position fundamentally shift and revitalise the global economy," says Rifkin.

The current system cannot sustain growing demand for resources. Instability, youth unemployment, environmental change, and inequality demand a systems scale shift. This shift won't happen by itself, it requires bold, determined investment in the new infrastructure.

This is not just an opportunity for growth, it is a necessity for social inclusion, environmental sustainability and global peace.

Related Skill

Book a class related to this article:

Want to get great at something? Get a coach

How do we improve in the face of complexity? Atul Gawande has studied this question with a surgeon's precision. He shares what he's found to be the key: having a good coach to provide a more accurate picture of our reality, to instill positive habits of thinking, and to break our actions down and then help us build them back up again. "It's not how good you are now; it's how good you're going to be that really matters," Gawande says.

How do we improve in the face of complexity? Atul Gawande has studied this question with a surgeon's precision. He shares what he's found to be the key: having a good coach to provide a more accurate picture of our reality, to instil positive habits of thinking, and to break our actions down and then help us build them back up again. "It's not how good you are now; it's how good you're going to be that really matters," Gawande says.

By Atul Gawande

How do professionals get better at what they do? How do they get great? I think it's not just how good you are now, I think it's how good you're going to be that really matters. As a surgeon getting better means I save more lives. And I have also seen the consequences of different philosophies of betterment around the world. I'd like to share what I have observed.

Dorothy DeLay with students

The Two Views of Professional Improvement

There are two views about this. One is the traditional pedagogical view. That is that you go to school, you study, you practice, you learn, you graduate, and then you go out into the world and you make your way on your own. A professional is someone who is capable of managing their own improvement. That is the approach that virtually all professionals have learned by. That's how doctors learn, that's how lawyers do, scientist, and musicians. And the thing is, it works. Consider for example legendary Juilliard violin instructor Dorothy DeLay. She trained an amazing roster of violin virtuosos: Midori, Sarah Chang, Itzhak Perlman. Each of them came to her as young talents, and they worked with her over years. What she worked on most, she said, was inculcating in them habits of thinking and of learning so that they could make their way in the world without her when they were done.

Now, the contrasting view comes out of sports. And they say "You are never done, everybody needs a coach." Everyone. The greatest in the world needs a coach.

So I tried to think about this as a surgeon. Pay someone to come into my operating room, observe me and critique me. That seems absurd. Expertise means not needing to be coached

So then which view is right?

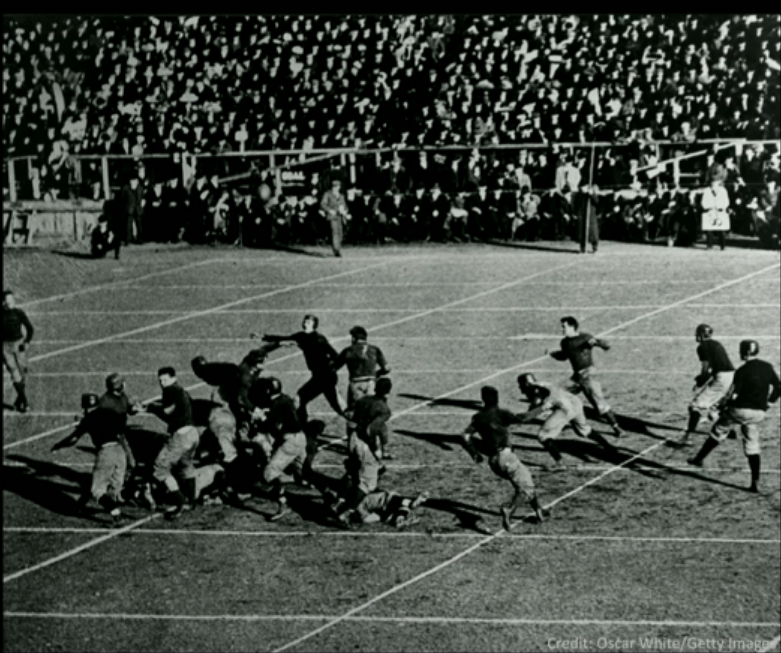

I learned that coaching came into sports as a very American idea. In 1875, Harvard and Yale played one of the very first American-rules football games. Yale hired a head coach; Harvard did not. The results? Over the next three decades, Harvard won just four times. Harvard hired a coach.

And it became the way that sports works. But is it necessary then? Does it transfer into other fields?

Itzhak Perlman

I decided to ask, of all people, Itzhak Perlman. He had trained the Dorothy DeLay way and became arguably the greatest violinist of his generation. One of the beautiful things about getting to write for "The New Yorker" is I call people up, and they return my phone calls.

And Perlman returned my phone call. So we ended up having an almost two-hour conversation about how he got to where he got in his career.

And I asked him, I said, "Why don't violinists have coaches?"

And he said, "I don't know, but I always had a coach."

"You always had a coach?"

"Oh yeah, my wife, Toby."

They had graduated together from Juilliard, and she had given up her job as a concert violinistto be his coach, sitting in the audience, observing him and giving him feedback.

"Itzhak, in that middle section, you know you sounded a little bit mechanical. What can you differently next time?" It was crucial to everything he became, he said.

My Own Coaching Experience

Turns out there are numerous problems in making it on your own. You don't recognize the issues that are standing in your way or if you do, you don't necessarily know how to fix them.And the result is that somewhere along the way, you stop improving. And I thought about that, and I realised that was exactly what had happened to me as a surgeon.

I'd entered practice in 2003, and for the first several years, it was just this steady, upward improvement in my learning curve. I watched my complication rates drop from one year to the next. And after about five years, they levelled out. And a few more years after that, I realised I wasn't getting any better anymore. And I thought: "Is this as good as I'm going to get?"

So I thought a little more and I said ... "OK, I'll try a coach." So I asked a former professor of mine who had retired, his name is Bob Osteen, and he agreed to come to my operating room and observe me. The case -- I remember that first case. It went beautifully. I didn't think there would be anything much he'd have to say when we were done. Instead, he had a whole page dense with notes.

"Just small things," he said.

But it's the small things that matter. "Did you notice that the light had swung out of the wound during the case?", he asked "You spent about half an hour just operating off the light from reflected surfaces". I hadn't noticed. "Another thing," he said, "Your elbow goes up in the air every once in a while. That means you're not in full control. A surgeon's elbows should be down at their sides resting comfortably. So that means if you feel your elbow going in the air, you should get a different instrument, or just move your feet." It was a whole other level of awareness. And I had to think, there was something fundamentally profound about this.

Osteen was doing what great coaches do: they are your external eyes and ears, providing a more accurate picture of your reality. They're recognising the fundamentals. They're breaking your actions down and then helping you build them back up again.

After two months of coaching, I felt myself getting better again. And after a year, I saw my complications drop down even further. It was painful. I didn't like being observed, and at times I didn't want to have to work on things. I also felt there were periods where I would get worse before I got better. But it made me realize that the coaches were onto something profoundly important.

Systems Scale Coaching

In my other work, I lead a health systems innovation centre called Ariadne Labs, where we work on problems in the delivery of health care, including global childbirth. As part of it, we had worked with the World Health Organization to devise a safe childbirth checklist. It lays out the fundamentals -- the critical actions a team needs to go through when a woman comes in in labor; when she's ready to push; when the baby is out; and then when the mom and baby are ready to go home. And we knew that just handing out a checklist wasn't going to change very much, and even just teaching it in the classroom wasn't necessarily going to be enough to get people to make the changes that you needed to bring it alive. And I thought on my experience and said:

““What if we tried coaching? What if we tried coaching at a massive scale?””

We found some incredible partners, including the government of India, and we ran a trial in 120 birth centres. In Uttar Pradesh, in India's largest state. Half of the centres we just observed, but the other half got visits from coaches. We trained an army of doctors and nurses in basic coaching practices - observation for a start.

One of the skills, they had to work on - that turned out to be fundamentally important - was communication. Getting the nurses to practice speaking up when the baby mask is broken, or the gloves are not in stock, or someone's not washing their hands. And then getting others, including the managers, to practice listening. This small army of coaches ended up coaching 400 nurses and other birth attendants, and 100 physicians and managers. We tracked the results across 160,000 births.

The results:

- In the control group who didn't have coaching they delivered on only one-third of 18 basic practices that we were measuring. And most important was that over the course of the years of study, we saw no improvement over time.

- In the other group, who got four months of coaching, we saw them increase to greater than two-thirds of the practices being delivered. It works. We could see the improvement in quality, and you could see it happen across a whole range of centres that suggested that coaching could be a whole line of way that we bring value to what we do.

With coaching at this scale, you can imagine the whole job category that could reach out in the world and that millions of people could fulfil.

Surgeon and public health professor by day, writer by night, Atul Gawande explores how doctors can dramatically improve their practice using approaches as simple as a checklist – or coaching. Atul Gawande is author of several best-selling books, including Complications: A Surgeon's Notes on an Imperfect Science, Better: A Surgeon's Notes on Performance, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End and The Checklist Manifesto.

This is an extract from a 2017 talk delivered by Atul Gawande entitled "Want to get great at something? Get a coach" delivered at TED2017, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

The secret to living longer may be your social life

The Italian island of Sardinia has more than six times as many centenarians as the mainland and ten times as many as North America. Why? According to psychologist Susan Pinker, it's not a sunny disposition or a low-fat, gluten-free diet that keeps the islanders healthy -- it's their emphasis on close personal relationships and face-to-face interactions. Learn more about super longevity as Pinker explains what it takes to live to 100 and beyond.

The Italian island of Sardinia has more than six times as many centenarians as the mainland and ten times as many as North America. Why? According to psychologist Susan Pinker, it's not a sunny disposition or a low-fat, gluten-free diet that keeps the islanders healthy -- it's their emphasis on close personal relationships and face-to-face interactions. Learn more about super longevity as Pinker explains what it takes to live to 100 and beyond.

By Susan Pinker

Here's an intriguing fact: In the developed world, everywhere, women live an average of six to eight years longer than men do. In 2015, The Lancet published an article showing that men in rich countries are twice as likely to die as women are at any age.

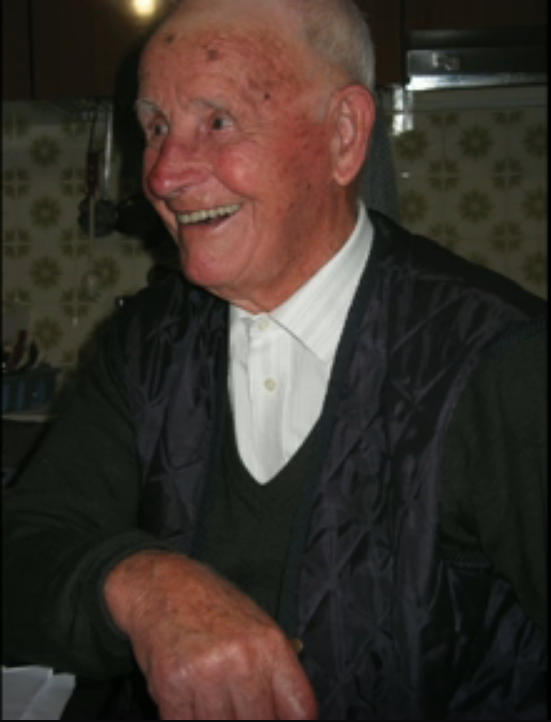

Sardinia, Italy

But there is one place in the world where men live as long as women. It's a remote, mountainous zone, a blue zone, where super longevity is common to both sexes. This is the blue zone in Sardinia, an Italian island in the Mediterranean, between Corsica and Tunisia, where there are six times as many centenarians as on the Italian mainland, less than 200 miles away. There are 10 times as many centenarians as there are in North America. It's the only place where men live as long as women.

But why? My curiosity was piqued. I decided to research the science and the habits of the place, and I started with the genetic profile. I discovered soon enough that genes account for just 25 percent of their longevity. The other 75 percent is lifestyle.

Villagrande: Epicenter of Sardinia's Blue Zone

So what does it take to live to 100 or beyond? What are they doing right?

What you're looking at is an aerial view of Villagrande. It's a village at the epicenter of the blue zone where I went to investigate this, and as you can see, architectural beauty is not its main virtue, density is: tightly spaced houses, interwoven alleys and streets. It means that the villagers' lives constantly intersect. And as I walked through the village, I could feel hundreds of pairs of eyes watching me from behind doorways and curtains, from behind shutters. Because like all ancient villages, Villagrande couldn't have survived without this structure, without its walls, without its cathedral, without its village square, because defense and social cohesion defined its design.

Urban priorities changed as we moved towards the industrial revolution because infectious disease became the risk of the day. But what about now? Now, social isolation is the public health risk of our time. Now, a third of the population says they have two or fewer people to lean on.

But let's go to Villagrande now as a contrast to meet some centenarians.

Giuseppe Murinu

Meet Giuseppe Murinu. He's 102, a supercentenarian and a lifelong resident of the village of Villagrande. He was a gregarious man. He loved to recount stories such as how he lived like a bird from what he could find on the forest floor during not one but two world wars, how he and his wife, who also lived past 100, raised six children in a small, homey kitchen where I interviewed him. He was a happy-go-lucky guy, very outgoing with a positive outlook. And I wondered: so is that what it takes to live to be 100 or beyond, thinking positively? Actually, no.

“Building in-person interaction into our cities, into our workplaces, into our agendas bolsters the immune system, sends feel-good hormones surging through the bloodstream and brain and helps us live longer. ”

Meet Giovanni Corrias. He's 101, the grumpiest person I have ever met

Giovanni Corrias

And he put a lie to the notion that you have to be positive to live a long life. And there is evidence for this. When I asked him why he lived so long, he kind of looked at me under hooded eyelids and he growled, "Nobody has to know my secrets."

But despite being a sourpuss, the niece who lived with him and looked after him called him "Il Tesoro," "my treasure." And she respected him and loved him, and she told me, when I questioned this obvious loss of her freedom, "You just don't understand, do you? Looking after this man is a pleasure. It's a huge privilege for me. This is my heritage." And indeed, wherever I went to interview these centenarians, I found a kitchen party. And I quickly discovered by being there that in the blue zone, as people age, and indeed across their lifespans, they're always surrounded by extended family, by friends, by neighbors, the priest, the barkeeper, the grocer. People are always there or dropping by. They are never left to live solitary lives. This is unlike the rest of the developed world, where as George Burns quipped, "Happiness is having a large, loving, caring family in another city."

Zia Teresa

Now, so far we've only met men, long-living men, but I met women too, and here you see Zia Teresa. She, at over 100, taught me how to make the local specialty, which is called culurgiones, which are these large pasta pockets like ravioli and they're filled with high-fat ricotta and mint and drenched in tomato sauce. And she showed me how to make just the right crimp so they wouldn't open, and she makes them with her daughters every Sunday and distributes them by the dozens to neighbors and friends. And that's when I discovered a low-fat, gluten-free diet is not what it takes to live to 100 in the blue zone.

Now, these centenarians' stories along with the science that underpins them prompted me to ask myself some questions too, such as, when am I going to die and how can I put that day off? And as you will see, the answer is not what we expect. Julianne Holt-Lunstad is a researcher at Brigham Young University and she addressed this very question in a series of studies of tens of thousands of middle aged people much like this audience here. And she looked at every aspect of their lifestyle: their diet, their exercise, their marital status, how often they went to the doctor, whether they smoked or drank, etc. She recorded all of this and then she and her colleagues sat tight and waited for seven years to see who would still be breathing. And of the people left standing, what reduced their chances of dying the most? That was her question.

So let's now look at her data in summary, going from the least powerful predictor to the strongest. OK? So clean air, which is great, it doesn't predict how long you will live. Whether you have your hypertension treated is good. Still not a strong predictor. Whether you're lean or overweight, you can stop feeling guilty about this, because it's only in third place. How much exercise you get is next, still only a moderate predictor. Whether you've had a cardiac event and you're in rehab and exercising, getting higher now. Whether you've had a flu vaccine. Did anybody here know that having a flu vaccine protects you more than doing exercise? Whether you were drinking and quit, or whether you're a moderate drinker, whether you don't smoke, or if you did, whether you quit, and getting towards the top predictors are two features of your social life.

by: Horst Gutmann

First, your close relationships. These are the people that you can call on for a loan if you need money suddenly, who will call the doctor if you're not feeling well or who will take you to the hospital, or who will sit with you if you're having an existential crisis, if you're in despair. Those people, that little clutch of people are a strong predictor, if you have them, of how long you'll live. And then something that surprised me, something that's called social integration. This means how much you interact with people as you move through your day. How many people do you talk to? And these mean both your weak and your strong bonds, so not just the people you're really close to, who mean a lot to you, but, like, do you talk to the guy who every day makes you your coffee? Do you talk to the postman? Do you talk to the woman who walks by your house every day with her dog? Do you play bridge or poker, have a book club? Those interactions are one of the strongest predictors of how long you'll live.

by: Zohaib Akhtar Photography

Now, this leads me to the next question: if we now spend more time online than on any other activity, including sleeping, we're now up to 11 hours a day, one hour more than last year, by the way, does it make a difference? Why distinguish between interacting in person and interacting via social media? Is it the same thing as being there if you're in contact constantly with your kids through text, for example? Well, the short answer to the question is no, it's not the same thing. Face-to-face contact releases a whole cascade of neurotransmitters, and like a vaccine, they protect you now in the present and well into the future. So simply making eye contact with somebody, shaking hands, giving somebody a high-five is enough to release oxytocin, which increases your level of trust and it lowers your cortisol levels. It lowers your stress and dopamine is generated, which gives us a little high and it kills pain. It's like a naturally produced morphine.

Now, all of this passes under our conscious radar, which is why we conflate online activity with the real thing. But we do have evidence now, fresh evidence, that there is a difference. So let's look at some of the neuroscience. Elizabeth Redcay, a neuroscientist at the University of Maryland, tried to map the difference between what goes on in our brains when we interact in person versus when we're watching something that's static. And what she did was she compared the brain function of two groups of people, those interacting live with her or with one of her research associates in a dynamic conversation, and she compared that to the brain activity of people who were watching her talk about the same subject but in a canned video, like on YouTube. And by the way, if you want to know how she fit two people in an MRI scanner at the same time, talk to me later.

So what's the difference? This is your brain on real social interaction. What you're seeing is the difference in brain activity between interacting in person and taking in static content. In orange, you see the brain areas that are associated with attention, social intelligence -- that means anticipating what somebody else is thinking and feeling and planning -- and emotional reward. And these areas become much more engaged when we're interacting with a live partner.

Now, these richer brain signatures might be why recruiters from Fortune 500 companiesevaluating candidates thought that the candidates were smarter when they heard their voicescompared to when they just read their pitches in a text, for example, or an email or a letter.Now, our voices and body language convey a rich signal. It shows that we're thinking, feeling,sentient human beings who are much more than an algorithm. Now, this research by Nicholas Epley at the University of Chicago Business School is quite amazing because it tells us a simple thing. If somebody hears your voice, they think you're smarter. I mean, that's quite a simple thing.

Now, to return to the beginning, why do women live longer than men? And one major reason is that women are more likely to prioritise and groom their face-to-face relationships over their lifespans. Fresh evidence shows that these in-person friendships create a biological force field against disease and decline. And it's not just true of humans but our primate relations as well. Anthropologist Joan Silk's work shows that female baboons who have a core of female friends show lower levels of stress via their cortisol levels, they live longer and they have more surviving offspring. At least three stable relationships. That was the magic number. Think about it. I hope you guys have three.

The power of such face-to-face contact is really why there are the lowest rates of dementia among people who are socially engaged. It's why women who have breast cancer are four times more likely to survive their disease than loners are. This face-to-face contact provides stunning benefits, yet now almost a quarter of the population says they have no one to talk to.

We can do something about this. Like Sardinian villagers, it's a biological imperative to know we belong, and not just the women among us. Building in-person interaction into our cities, into our workplaces, into our agendas bolsters the immune system, sends feel-good hormones surging through the bloodstream and brain and helps us live longer. I call this building your village, and building it and sustaining it is a matter of life and death.

Susan Pinker reveals how in-person social interactions are not only necessary for human happiness but also could be a key to health and longevity. With The Village Effect, she tracks how social, face-to-face interactions are critical not only for our happiness but also for our survival, and how technology can isolate us from these life-saving bonds.

This is an extract from a 2017 talk delivered by Susan Pinker entitled "The secret to living longer may be your social life" delivered at TED2017, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

5 ways to lead in an era of constant change

Who says change needs to be hard? Organizational change expert Jim Hemerling thinks adapting your business in today's constantly-evolving world can be invigorating instead of exhausting. He outlines five imperatives, centered around putting people first, for turning company reorganization into an empowering, energizing task for all.

Who says change needs to be hard? Organizational change expert Jim Hemerling thinks adapting your business in today's constantly-evolving world can be invigorating instead of exhausting. He outlines five imperatives, centered around putting people first, for turning company reorganization into an empowering, energizing task for all.

Have you ever noticed when you ask someone to talk about a change they're making for the better in their personal lives, they're often really energetic? Whether it's training for a marathon, picking up an old hobby, or learning a new skill, for most people, self-transformation projects occupy a very positive emotional space.

When it comes to self-transformation, you can't help but get a sense of the excitement. But there's another type of transformation that occupies a very different emotional space. The transformation of organizations. If you're like most people, when you hear the words "Our organization is going to start a transformation," you're thinking, "Uh-oh."

"Layoffs." The blood drains from your face, your mind goes into overdrive, frantically searching for some place to run and hide.

Well, you can run, but you really can't hide. Most of us spend the majority of our waking hours involved in organizations. And due to changes in globalization, changes due to advances in technology and other factors, the reality is our organizations are constantly having to adapt. In fact, I call this the era of "always-on" transformation.

“People naturally resist change, especially when it’s imposed on them”

When I shared this idea with my wife Nicola, she said, "Always-on transformation? That sounds exhausting." And that may be exactly what you're thinking -- and you would be right. Particularly if we continue to approach the transformation of organizations the way we always have been.

But because we can't hide, we need to sort out two things. First, why is transformation so exhausting? And second, how do we fix it?

First of all, let's acknowledge that change is hard. People naturally resist change, especially when it's imposed on them. But there are things that organizations do that make change even harder and more exhausting for people than it needs to be. Leaders often wait too long to act. As a result, everything is happening in crisis mode. Which, of course, tends to be exhausting. Or, given the urgency, what they'll do is they'll just focus on the short-term results, but that doesn't give any hope for the future. Or they'll just take a superficial, one-off approach, hoping that they can return back to business as usual as soon as the crisis is over.

So given these obstacles, what can we do to transform the way we transform organizations so rather than being exhausting, it's actually empowering and energizing?

To do that, we need to focus on five strategic imperatives, all of which have one thing in common: putting people first.

The first imperative for putting people first is to inspire through purpose. Most transformations have financial and operational goals. These are important and they can be energizing to leaders, but they tend not to be very motivating to most people in the organization. To motivate more broadly, the transformation needs to connect with a deeper sense of purpose.

Take LEGO. The LEGO Group has become an extraordinary global company. Under their very capable leadership, they've actually undergone a series of transformations. While each of these has had a very specific focus, the North Star, linking and guiding all of them, has been Lego's powerful purpose: inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow. Expanding globally? It's not about increasing sales, but about giving millions of additional children access to LEGO building bricks. Investment and innovation? It's not about developing new products, but about enabling more children to experience the joy of learning through play. Not surprisingly, that deep sense of purpose tends to be highly motivating to LEGO's people.

Photo credit: recombiner

The second imperative for putting people first is to go all in. Too many transformations are nothing more than head-count cutting exercises; layoffs under the guise of transformation. In the face of relentless competition, it may well be that you will have to take the painful decision to downsize the organization, just as you may have to lose some weight in order to run a marathon. But losing weight alone will not get you across the finish line with a winning time. To win you need to go all in. You need to go all in. Rather than just cutting costs, you need to think about initiatives that will enable you to win in the medium term, initiatives to drive growth, actions that will fundamentally change the way the company operates, and very importantly, investments to develop the leadership and the talent.

The third imperative for putting people first is to enable people with the capabilities that they need to succeed during the transformation and beyond. Over the years I've competed in a number of triathlons. You know, frankly, I'm not that good, but I do have one distinct capability; I am remarkably fast at finding my bike.

By the time I finish the swim, almost all the bikes are already gone.

Real triathletes know that each leg -- the swim, the bike, the run -- really requires different capabilities, different tools, different skills, different techniques. Likewise when we transform organizations, we need to be sure that we're giving our people the skills and the tools they need along the way.

Chronos, a global software company, recognized the need to transfer from building products -- software products -- to building software as a service. To enable its people to take that transformation, first of all they invested in new tools that would enable their employees to monitor the usage of the features as well as customer satisfaction with the new service. They also invested in skill development, so that their employees would be able to resolve customer service problems on the spot. And very importantly, they also reinforced the collaborative behaviors that would be required to deliver an end-to-end seamless customer experience. Because of these investments, rather than feeling overwhelmed by the transformation, Chronos employees actually felt energized and empowered in their new roles.

In the era of "always-on" transformation, change is a constant.

Photo credit: recombiner

My fourth imperative therefore is to instill a culture of continuous learning. When Satya Nadella became the CEO of Microsoft in February 2014, he embarked on an ambitious transformation journey to prepare the company to compete in a mobile-first, cloud-first world. This included changes to strategy, the organization and very importantly, the culture. Microsoft's culture at the time was one of silos and internal competition -- not exactly conducive to learning. Nadella took this head-on. He rallied his leadership around his vision for a living, learning culture, shifting from a fixed mindset, where your role was to show up as the smartest person in the room, to a growth mindset, where your role was to listen, to learn and to bring out the best in people. Well, early days, Microsoft employees already noticed this shift in the culture -- clear evidence of Microsoft putting people first.

My fifth and final imperative is specifically for leaders. In a transformation, a leader needs to have a vision, a clear road map with milestones, and then you need to hold people accountable for results. In other words, you need to be directive. But in order to capture the hearts and minds of people, you also need to be inclusive. Inclusive leadership is critical to putting people first.

In the era of "always-on" transformation, organizations are always going to be transforming. But doing so does not have to be exhausting.

We owe it to ourselves, to our organizations and to society more broadly to boldly transform our approach to transformation. To do that, we need to start putting people first.

Jim Hemerling is a Senior Partner and Managing Director in The Boston Consulting Group's People & Organization and Transformation Practices. He is a BCG Fellow with a focus on high-performance organization transformation. He also leads BCG's global Behavior & Culture topic.

This is an extract from a 2016 talk delivered by Jim Hemerling entitled "5 ways to lead in an era of constant change" delivered at TED@BCG Paris, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

If a story moves you, act on it

Stories are necessary, but they're not as magical as they seem, says writer Sisonke Msimang. In this funny and thoughtful talk, Msimang questions our emphasis on storytelling and spotlights the decline of facts. During a critical time when listening has been confused for action, Msimang asks us to switch off our phones, step away from our screens and step out into the real world to create a plan for justice.

Stories are necessary, but they're not as magical as they seem, says writer Sisonke Msimang. In this funny and thoughtful talk, Msimang questions our emphasis on storytelling and spotlights the decline of facts. During a critical time when listening has been confused for action, Msimang asks us to switch off our phones, step away from our screens and step out into the real world to create a plan for justice.

I'm here to talk about my own observations about storytelling. I want to talk to you about the power of stories, of course, but I also want to talk about their limitations, particularly for those of us who are interested in social justice.

Stories are everywhere, and if there was a danger in the telling of one tired old tale, then I think there has got to be lots to celebrate about the flourishing of so many stories and so many voices. Stories are the antidote to bias. In fact, today, if you are middle class and connected via the internet, you can download stories at the touch of a button or the swipe of a screen. You can listen to a podcast about what it's like to grow up Dalit in Kolkata. You can hear an indigenous man in Australia talk about the trials and triumphs of raising his children in dignity and in pride. Stories make us fall in love. They heal rifts and they bridge divides. Stories can even make it easier for us to talk about the deaths of people in our societies who don't matter, because they make us care. Right?

“If it is justice that we are after, then I think we mustn’t focus on the media or the storytellers. We must focus on audiences, on anyone who has ever turned on a radio or listened to a podcast, and that means all of us”

I'm not so sure, and I actually work for a place called the Centre for Stories. And my job is to help to tell stories that challenge mainstream narratives about what it means to be black or a Muslim or a refugee or any of those other categories that we talk about all the time. But I come to this work after a long history as a social justice activist, and so I'm really interested in the ways that people talk about nonfiction storytelling as though it's about more than entertainment, as though it's about being a catalyst for social action. It's not uncommon to hear people say that stories make the world a better place. Increasingly, though, I worry that even the most poignant stories, particularly the stories about people who no one seems to care about, can often get in the way of action towards social justice. Now, this is not because storytellers mean any harm. Quite the contrary. Storytellers are often do-gooders like me and, I suspect, yourselves. And the audiences of storytellers are often deeply compassionate and empathetic people. Still, good intentions can have unintended consequences, and so I want to propose that stories are not as magical as they seem.

So three -- because it's always got to be three -- three reasons why I think that stories don't necessarily make the world a better place.

Firstly,

stories can create an illusion of solidarity. There is nothing like that feel-good factor you get from listening to a fantastic story where you feel like you climbed that mountain, right, or that you befriended that death row inmate. But you didn't. You haven't done anything. Listening is an important but insufficient step towards social action.

Secondly,

I think often we are drawn towards characters and protagonists who are likable and human. And this makes sense, of course, right? Because if you like someone, then you care about them. But the inverse is also true. If you don't like someone, then you don't care about them. And if you don't care about them, you don't have to see yourself as having a moral obligation to think about the circumstances that shaped their lives.

Thirdly,

I think that stories don't necessarily make the world a better place because too often we are so invested in the personal narrative that we forget to look at the bigger picture. And so we applaud someone when they tell us about their feelings of shame, but we don't necessarily link that to oppression. We nod understandingly when someone says they felt small, but we don't link that to discrimination. The most important stories, especially for social justice, are those that do both, that are both personal and allow us to explore and understand the political.

Photo credit: recombiner

But it's not just about the stories we like versus the stories we choose to ignore.

Increasingly, we are living in a society where there are larger forces at play, where stories are actually for many people beginning to replace the news. We live in a time where we are witnessing the decline of facts, when emotions rule and analysis, it's kind of boring, right? Where we value what we feel more than what we actually know. A recent report by the Pew Center on trends in America indicates that only 10 percent of young adults under the age of 30 "place a lot of trust in the media." Now, this is significant. It means that storytellers are gaining trust at precisely the same moment that many in the media are losing the confidence in the public. This is not a good thing, because while stories are important and they help us to have insights in many ways, we need the media. From my years as a social justice activist, I know very well that we need credible facts from media institutions combined with the powerful voices of storytellers. That's what pushes the needle forward in terms of social justice.

In the final analysis, of course, it is justice that makes the world a better place, not stories. Right? And so if it is justice that we are after, then I think we mustn't focus on the media or on storytellers. We must focus on audiences, on anyone who has ever turned on a radio or listened to a podcast, and that means all of us.

So a few concluding thoughts on what audiences can do to make the world a better place:

- The world would be a better place, I think, if audiences were more curious and more skeptical and asked more questions about the social context that created those stories that they love so much.

- The world would be a better place if audiences recognized that storytelling is intellectual work. And I think it would be important for audiences to demand more buttons on their favorite websites, buttons for example that say, "If you liked this story, click here to support a cause your storyteller believes in." Or "click here to contribute to your storyteller's next big idea." Often, we are committed to the platforms, but not necessarily to the storytellers themselves.

- I think that audiences can make the world a better place by switching off their phones, by stepping away from their screens and stepping out into the real world beyond what feels safe.

Alice Walker has said, "Look closely at the present you are constructing. It should look like the future you are dreaming."

Storytellers can help us to dream, but it's up to all of us to have a plan for justice.

Sisonke Msimang tells stories about justice and human rights. In the early part of her career, Msimang set up a fund fight for people whose health had been compromised by their race, class and gender identities. In 2008 she became the executive director of the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, responsible for making grants on human rights projects. Msimang is now the head of programs at the Centre for Stories, a new initiative that collects, preserves and shares stories about migrants, refugees and diverse people and places linked to the Indian Ocean Rim.

This is an extract from a 2016 talk delivered by Sisonke Msimang entitled "If a story moves you, act on it" delivered at TEDWomen, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

What do we do with all this big data?

Does a set of data make you feel more comfortable? More successful? Then your interpretation of it is likely wrong. In a surprisingly moving talk, Susan Etlinger explains why, as we receive more and more data, we need to deepen our critical thinking skills. Because it's hard to move beyond counting things to really understanding them.

Does a set of data make you feel more comfortable? More successful? Then your interpretation of it is likely wrong. In a surprisingly moving talk, Susan Etlinger explains why, as we receive more and more data, we need to deepen our critical thinking skills. Because it's hard to move beyond counting things to really understanding them.

Technology has brought us so much: the moon landing, the Internet, the ability to sequence the human genome. But it also taps into a lot of our deepest fears, and about 30 years ago, the culture critic Neil Postman wrote a book called "Amusing Ourselves to Death," which lays this out really brilliantly, comparing the dystopian visions of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley. He said, Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture. Orwell feared the truth would be concealed from us, and Huxley feared we would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. In a nutshell, it's a choice between Big Brother watching you and you watching Big Brother.

But it doesn't have to be this way. We are not passive consumers of data and technology. We shape the role it plays in our lives and the way we make meaning from it, but to do that, we have to pay as much attention to how we think as how we code. We have to ask questions, and hard questions, to move past counting things to understanding them. We're constantly bombarded with stories about how much data there is in the world, but when it comes to big data and the challenges of interpreting it, size isn't everything. There's also the speed at which it moves, and the many varieties of data types. What unites this disparate types of data is that they're created by people and they require context.

It's not just big data that causes challenges of interpretation, because let's face it, we human beings have a very rich history of taking any amount of data, no matter how small, and screwing it up. Many years ago, you may remember that former President Ronald Reagan was very criticized for making a statement that facts are stupid things. And it was a slip of the tongue, let's be fair. He actually meant to quote John Adams' defense of British soldiers in the Boston Massacre trials that facts are stubborn things. But I actually think there's a bit of accidental wisdom in what he said, because facts are stubborn things, but sometimes they're stupid, too.

“The challenge is that we have this opportunity to make meaning out of data ourselves, because frankly, data doesn’t create meaning... we have a responsibility to spend more time focusing on our critical thinking skills”

Facts are stupid things. And they're vulnerable to misuse, willful or otherwise. I have a friend, Emily Willingham, who's a scientist, and she wrote a piece for Forbes not long ago entitled "The 10 Weirdest Things Ever Linked to Autism." It's quite a list. The Internet, blamed for everything, right? And of course mothers... there's a whole bunch in the "mother" category here. And you can see it's a pretty rich and interesting list. I'm a big fan of being pregnant near freeways, personally. The final one is interesting, because the term "refrigerator mother" was actually the original hypothesis for the cause of autism, and that meant somebody who was cold and unloving.

And at this point, you might be thinking, "Okay, Susan, we get it, you can take data, you can make it mean anything." And this is true, it's absolutely true, but the challenge is that we have this opportunity to try to make meaning out of it ourselves, because frankly, data doesn't create meaning. We do. So as businesspeople, as consumers, as patients, as citizens, we have a responsibility, I think, to spend more time focusing on our critical thinking skills.

Why?

Because at this point in our history, as we've heard many times over, we can process exabytes of data at lightning speed, and we have the potential to make bad decisions far more quickly, efficiently, and with far greater impact than we did in the past. Great, right? And so what we need to do instead is spend a little bit more time on things like the humanities and sociology, and the social sciences, rhetoric, philosophy, ethics, because they give us context that is so important for big data, and because they help us become better critical thinkers. Because after all, if I can spot a problem in an argument, it doesn't much matter whether it's expressed in words or in numbers. And this means teaching ourselves to find those confirmation biases and false correlations.

And it means questioning disciplines like demographics. Why? Because they're based on assumptions about who we all are based on our gender and our age and where we live as opposed to data on what we actually think and do. And since we have this data, we need to treat it with appropriate privacy controls and consumer opt-in, and beyond that, we need to be clear about our hypotheses, the methodologies that we use, and our confidence in the result. As my high school algebra teacher used to say, show your math, because if I don't know what steps you took, I don't know what steps you didn't take, and if I don't know what questions you asked, I don't know what questions you didn't ask. And it means asking ourselves the hardest question of all:

Did the data really show us this, or does the result make us feel more successful and more comfortable?

If we are to unlock the power of data, we don't have to go blindly into Orwell's vision of a totalitarian future, or Huxley's vision of a trivial one, or some horrible cocktail of both. What we have to do is treat critical thinking with respect and, as they say in the superhero movies, let's use our powers for good.

Susan Etlinger is an industry analyst with Altimeter Group, where she focuses on data and analytics. She conducts independent research and has authored two intriguing reports: “The Social Media ROI Cookbook” and “A Framework for Social Analytics.” She also advises global clients on how to work measurement into their organizational structure and how to extract insights from the social web which can lead to tangible actions.

This is an extract from a 2014 talk delivered by Susan Etlinger entitled "What do we do with all this big data?" delivered at TED@IBM, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Future Skills for Inclusion

The technological world is growing faster than ever, bringing the Fourth Industrial Revolution even closer to being our reality. The First Industrial Revolution brought us mechanisation, the Second brought mass production and the Third introduced computers and automation. But what about the Fourth Industrial Revolution? What does it entail and what does it mean for us?

On Wednesday, 9 May 2018, the World Economic Forum led the Shaping Inclusive Growth in The Fourth Industrial Revolution workshop. Key thinkers explored and discussed what facets of The Fourth Industrial Revolution can harness and promote inclusive growth in Africa. Below is an overview of the central ideas surrounding the Fourth Industrial Revolution and its numerous implications:

The technological world is growing faster than ever, bringing the Fourth Industrial Revolution even closer to being our reality. The First Industrial Revolution brought us mechanisation, the Second brought mass production and the Third introduced computers and automation. But what about the Fourth Industrial Revolution? What does it entail and what does it mean for us?

The World Economic Forum (WEF), in the 2018 Readiness for the Future of Production Report, described the core features of the Fourth Industrial Revolution as follows:

“Technologies are transcending the computing capabilities associated with the digital revolution, transforming the physical world through robotics and new methods of production; enhancing human beings physically, mentally, and experientially; and permeating the environment to facilitate greater interconnectivity, monitoring, and efficiency of resource use”

Put simply, the world’s technologies are developing incredibly quickly, in a variety of ways, and it is largely positive - there are innumerable benefits that this sort of technological transformation can bring, but the way we live and work will have to change in the process. One of the biggest fears regarding the Fourth Industrial Revolution and its implications, is that people will lose their jobs, en masse. And it is a scary thought to imagine a bunch of really advanced machines and AI systems developing to the point where they replace you. WEF noted that these technological developments “...are spurring the development of new production techniques, business models, and value chains that will fundamentally transform global production” (Readiness for the Future of Production Report, 2018). In other words, the Fourth Industrial Revolution does mean massive change in terms of jobs and, more generally, the way global production is conducted.

But that is not the end of the story - thankfully, the Fourth Industrial Revolution doesn’t have to mean that a machine comes along, steals your job and leaves you in the dust. It does, however, mean that we need to shift the way we look at jobs, education and skills in order to be equipped to both differentiate ourselves from machines, as well as complement their abilities. Of course this requires individuals to be proactive in their own skill development, but WEF also notes that:

“...countries need to build awareness of the changing nature of production, determine how to best prepare to benefit from this transformation and collaborate across the public and private sector to enhance readiness”

Seems obvious, right? Prepare for the Fourth Industrial Revolution as we see it on the horizon, and make sure your country and citizens are skilled enough to benefit from it instead of suffer. Unfortunately, no one is there yet and “no country has reached the frontier of readiness, let alone harnessed the full potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution in production” (WEF, 2018). With technological development moving as quickly as it is, it’s imperative for countries to adapt and change in ways that not only welcomes this progress, but take full advantage of the opportunities that will come with it. This means investing time, money and significant energy in reskilling people to leave replaceable jobs behind, and become invaluable in their differentiation from machines.

“Moving forward, people, employers and policy makers alike need to realise that success in the Fourth Industrial Revolution lies in the individual’s ability to both differentiate from and complement machines”

So, we know what the Fourth Industrial Revolution is, what it’s implications are and what we should be doing, but what is really happening around the world? People are scared. Scared about the fact that “disruptive technological and socio-economic forces threaten to swiftly outdate the shelf life of people’s skillsets and the relevance of what they thought they knew about the path to social mobility and rewarding employment,” and this is in part because of a lack of “willingness to make a reasonable investment in reskilling that will bridge workers onto new jobs” (WEF, 2018). This needs to change because employers simply cannot maintain hiring an entirely new workforce each time a new skill set is required. Rather, there needs to be an increased focus on “reskilling and human capital development.” Workers should also be actively engaged in developing their skill-set, as it removes job insecurity to a large degree, and opens the door to a range of job and career opportunities that are likely more meaningful, stable and fulfilling. Who wants to do a job that a machine can do, anyway?

The world is changing, and The Fourth Industrial Revolution is bringing of the most transformational developments to our lives. Moving forward, people, employers and policy-makers alike need to realise that success in the Fourth Industrial Revolution lies in the individual’s ability to both differentiate from and complement machines, working with them rather than in opposition to them. WEF notes that a key facet of The Fourth Industrial Revolution is the uncertainty of it, specifically because we are not even aware of what skills will be essential in the future.

Preparation is necessary, as WEF notes in their 2018 Towards a Reskilling Revolution Insight report:

“To make reskilling real, and prepare for accelerated structural change of the labour market, a wide range of stakeholders — governments, employers, individuals, educational institutions and labour unions, among others — will need to learn to come together, collaborate and pool their resources more than ever before.”