The longevity of stories

We need stories. To communicate, to understand, to relate to each other, to explain. People have, throughout time and history, incorporated storytelling (and storymaking) into their lives, because it's how we make sense of the dynamic, often complex, situations we find ourselves in. Neil Gaiman, a master storyteller, outlines the importance of a good story, and the ability stories have to shape culture and behaviour

We need stories. To communicate, to understand, to relate to each other, to explain. People have, throughout time and history, incorporated storytelling (and storymaking) into their lives, because it's how we make sense of the dynamic, often complex, situations we find ourselves in. Neil Gaiman, a master story teller, outlines the importance of a good story, and the ability stories have to shape culture and behaviour:

By Neil Gaiman

Stories aren’t books. Books are simply one of the many storage mechanisms in which stories can be kept and, obviously, people are one of the other storage mechanisms. Stories change. The professions, the media that we use to store, record and transmit stories will change. Not long ago the people who stored and transmitted information were stonemasons. Now, not so much. Unless we want the information to last.

As individuals, we are cut off from humanity. As individuals, we are naked, we do not even know which plants will kill us. Without the mass of human knowledge accumulated over millennia to buoy us up, we are in big trouble. With it, we are warm, fed, we have popcorn, we are sitting in comfortable seats and we are capable of arguing with each other about really stupid things on the internet. That's because we have stories, it's because we have information.

In 1984 a man, whose name I don't know how to pronounce, I think it's Thomas Sebeok, wrote a report for the Department of Energy. He was asked to create a report because they had a problem - what to do with nuclear waste repositories. They needed to devise a method of warning future generations not to mine or drill at that site unless they're aware of the other consequences of their actions… and because the stuff that they would be putting in these nuclear waste repositories had a half-life of 10000 years, they needed to figure out ways to get information to last 10000 years. They started by looking at all you can write. The trouble with writing things is that it lasts a certain amount of time, but anyone here who’s actually tried to read Beowulf in the original knows that that only takes you so far. Language changes. Words change meaning. And if language is changing, what about pictographics? What if you put a big skull up? And Thomas pointed out that even a skull means different things in different cultures - some cultures might go “ahh, skull, symbol of warning,” some might go, “symbol of fantastic candy days. This is the place where the good stuff!”.

ISO Radiation Warning Sign

What he actually came up with, he said that the prime recommendation of the Human Interference Task Force of Department of Energy was that information be launched and artificially passed down into the short-term and long-term future, with these supplementary aid of folkloristic devices, in particular a combination of artificially created and nurtured ritual and legend. The most positive aspect of such a procedure is it need not be geographically localised, or tied to any one language or culture. So, the initiated would be steered away from the hazardous site, for reasons other than the scientific knowledge of the possibility of radiation and its implications, essentially the reason would be accumulated superstition to shun a certain area permanently.

A ritual with the legend retold year by year, with presumably slight variation. The actual “truth” would be entrusted exclusively to, what we might call for dramatic emphasis, an ‘atomic priesthood’ - it is a commission of knowledgeable physicists, experts in radiation sickness, anthropologists and whatever additional expertise may be called for in the future. Folklore specialists that they’d consulted say they know of no precedent, nor could they think of a parallel situation, except the well-known but ineffectual curse is associated with the burial sites of some Egyptian Pharaohs, which didn't deter greedy grave robbers from digging for hidden treasure.

“What we can do, I think, is try and create stories that are interesting enough and important enough that our grandchildren might want to tell those stories to their grandchildren. Because that’s the purpose of stories. It’s what they’re for. ”

First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang

Terracotta Warrior

Which is true, up to a point. The first emperor of China died 2000 years ago, and the site of his tomb was lost. Very intentionally lost - he killed anybody who knew where it was. It was a magnificent act of tomb losing. And then one day, in a field in China, somebody unearthed a Terracotta Warrior. And then they found another one. They excavated warriors and archaeologists worked out very quickly where the actual mausoleum had to be. The stories that come down to us 2300 years after the emperor China at died, now became a warning. Remember those lakes of mercury? That stuff is really poisonous. It doesn't even have a half-life, it's just there. As Terry Pratchett once said, “Radiation is 10000 years, arsenic is forever,” and so they didn't immediately start digging, instead they checked, confirmed the presence of incredibly high quantities of mercury and have been figuring out what to do ever since. And when they figure out how to get in there without dying, they will start excavating.

The Long Now, and the clock of The Long Now is about planning for the long term, and thinking in the long term, in a world in which people appear to be thinking in the shorter and shorter term, not even necessarily at this point about things that will take them to the end of their lifetime, which at least at one point you would have thought, “well, you know, I'll be dead before that's a problem,” looking around now, the mess we’re making of things on his planet. You wanna go to people and say, “you know actually, you will be. You will still be around. We could run out of water, you'll be here, having to figure out what to do with no water. What to do when the oceans are screwed up. What to do when Twitter finally becomes sentient.

Tom Sebeok concluded that you couldn’t actually create a story that would last 10000 years, you could only create a story that would last a 3 Generations - for ourselves, for our children, for their children. But what we can do, I think, is try and create stories that are interesting enough and important enough that our grandchildren might want to tell those stories to their grandchildren. Because that's the purpose of stories. It's what they’re for. They make life worth living and, sometimes, they keep us alive

Neil Gaiman has told stories in every medium—graphic novels (The Sandman), novels (The Ocean at the End of the Lane; American Gods), short stories (Trigger Warning), children’s books (The Graveyard Book), television (Dr Who), and the occasional song (“I Google You”)

This is an extract from a 2015 talk delivered by Neil Gaiman entitled "How Stories Last" delivered for the Long Now Foundation, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

A tangible demonstration of the power of storytelling: The significant objects experiment

The Significant Objects experiment is a tangible demonstration of the power of storytelling in sales and marketing. Journalist Rob Walker purchased low value objects, for on average $1.25 and had great creative writers invent stories about them. He then posted the articles on e-Bay to see if the invented story enhanced the value of the object based on what price it achieves on auction.

It did.

The Significant Objects experiment is a tangible demonstration of the power of storytelling in sales and marketing.

Journalist Rob Walker purchased low value objects, for on average $1.25 and had great creative writers invent stories about them. He then posted the articles on e-Bay to see if the invented story enhanced the value of the object based on what price it achieves on auction.

It did.

An old pepper shaker was bought for 99 cents, and sold for $28.00. A butterfly embossed cigarette case was bought for 10 cents, and sold for $33.77. A horse bust was bought for 99c and sold for $62.95

All in all, 100 pieces were cost $128.74, and were sold for $3612.51 - a whopping 2780% increase in value.

That's story power.

This apple was bought for $1.00, and sold for $102.50 with a story.

Cultural Cartography: How Buzzfeed organises their content

Last year, Buzzfeed started a project to formally categorize their content. They called it "cultural cartography." It formalized an informal practice that they've had for a really long time: don't just think about the subject matter; think also about, and in fact, primarily about, the job that your content is doing for the reader or the viewer.

By Dao Nguyen

Last year, some BuzzFeed employees were scheming to prank their boss, Ze Frank, on his birthday. They decided to put a family of baby goats in his office.

BuzzFeed had recently signed on to the Facebook Live experiment, and so naturally, we decided to livestream the whole event on the internet to capture the moment when Ze would walk in and discover livestock in his office. We thought the whole thing would last maybe 10 minutes, and a few hundred company employees would log in for the inside joke. But what happened? They kept on getting delayed: he went to get a drink, he was called to a meeting, the meeting ran long, he went to the bathroom. More and more people started logging in to watch the goats. By the time Ze walked in more than 30 minutes later, 90,000 viewers were watching the livestream.

Now, our team had a lot of discussion about this video and why it was so successful. It wasn't the biggest live video that we had done to date (the biggest one that we had done involved a fountain of cheese). But it performed so much better than we had expected. What was it about the goats in the office that we didn't anticipate?

Now, a reasonable person could have any number of hypotheses. Maybe people love baby animals. Maybe people love office pranks. Maybe people love stories about their bosses or birthday surprises. But our team wasn't really thinking about what the video was about. We were thinking about what the people watching the video were thinking and feeling. We read some of the 82,000 comments that were made during the video, and we hypothesized that they were excited because they were participating in the shared anticipation of something that was about to happen. They were part of a community, just for an instant, and it made them happy.

So we decided that we needed to test this hypothesis. What could we do to test this very same thing? The following week, armed with the additional knowledge that food videos are very popular, we dressed two people in hazmat suits and wrapped rubber bands around a watermelon until it exploded.

Eight hundred thousand people watched the 690th rubber band explode the watermelon, marking it as the biggest Facebook Live event to date.

The question I get most frequently is: How do you make something go viral? The question itself is misplaced; it's not about the something. It's about what the people doing the something - reading or watching - what are they thinking?

Now, most media companies, when they think about metadata, they think about subjects or formats. It's about goats, it's about office pranks, it's about food, it's a list or a video or a quiz, it's 2,000 words long, it's 15 minutes long, it has 23 embedded tweets or 15 images. Now, that kind of metadata is mildly interesting, but it doesn't actually get at what really matters. What if, instead of tagging what articles or videos are about, what if we asked: How is it helping our users do a real job in their lives?

The Cultural Cartography of Social Content

Last year, we started a project to formally categorize our content in this way. We called it, "cultural cartography." It formalized an informal practice that we've had for a really long time: don't just think about the subject matter; think also about, and in fact, primarily about, the job that your content is doing for the reader or the viewer.

Let me show you the map that we have today. Each bubble is a specific job, and each group of bubbles in a specific color are related jobs.

First up: humour. "Makes me laugh." There are so many ways to make somebody laugh. You can be laughing at someone, you could laugh at specific internet humour, you could be laughing at some good, clean, inoffensive dad jokes.

"This is me." Identity. People are increasingly using media to explain, "This is who I am. This is my upbringing, this is my culture, this is my fandom, this is my guilty pleasure, and this is how I laugh about myself."

The "Helps me Connect with Another Person" category

"Helps me connect with another person." This is one of the greatest gifts of the internet. It's amazing when you find a piece of media that precisely describes your bond with someone. The green bubbles make up the group of jobs that help me do something -- 'helps me settle an argument'; 'helps me learn something about myself or another person'; or 'helps me explain my story'.

The orange bubbles are the group of jobs that makes me feel something -- makes me curious or sad or restores my faith in humanity.

“If we can capture in data what really matters to you, and if we can understand the role that our work plays in your actual life, the better content we can create for you, and the better that we can reach you”

Many media companies and creators do put themselves in their audiences' shoes. But in the age of social media, we can go much farther. People are connected to each other on Facebook, on Twitter, and they're increasingly using media to have a conversation and to talk to each other. If we can be a part of establishing a deeper connection between two people, then we will have done a real job for these people.

Let me give you an example of how this plays out. This is one of my favorite lists: "32 Memes You Should Send Your Sister Immediately". It has things that are relatable, like: "When you're going through your sister's stuff, and you hear her coming up the stairs." Absolutely, I've done that. "Watching your sister get in trouble for something that you did and blamed on her." Yes, I've done that as well. This list got three million views. Why is that? Because it did, very well, several jobs: "This is us." "Connect with family." "Makes me laugh."

Now, we can even apply this framework to recipes and food. A recipe's normal job is to tell you what to make for dinner or for lunch. And this is how you would normally brainstorm for a recipe: you figure out what ingredients you want to use, what recipe that makes, and then maybe you slap a job on at the end to sell it. But what if we flipped it around and thought about the job first? One brainstorming session involved the job of bonding. So, could we make a recipe that brought people together? This is not a normal brainstorming process at a food publisher. So we know that people like to bake together, and we know that people like to do challenges together, so we decided to come up with a recipe that involved those two things, and we challenged ourselves: Could we get people to say, "Hey, BFF, let's see if we can do this together"? The resulting video was the "Fudgiest Brownies Ever" video. It was enormously successful in every metric possible -- 50 million views. And people said the exact things that we were going after: "Hey, Colette, we need to make these, are you up for a challenge?" "Game on." It did the job that it set out to do, which was to bring people together over baking and chocolate.

Metadata and Storymaking

I'm really excited about the potential for this project. When we talk about this framework with our content creators, they instantly get it, no matter what beat they cover, what country they’re in, or what language they speak. So cultural cartography has helped us massively scale our workforce training. When we talk about this project and this framework with advertisers and brands, they also instantly get it, because advertisers, more often than media companies, understand how important it is to understand the job that their products are doing for customers.

But the reason I'm the most excited about this project is because it changes the relationship between media and data. Most media companies think of media as "mine." How many fans do I have? How many followers have I gained? How many views have I gotten? How many unique IDs do I have in my data warehouse? But that misses the true value of data, which is that it's yours. If we can capture in data what really matters to you, and if we can understand more the role that our work plays in your actual life, the better content we can create for you, and the better that we can reach you.

Who are you? How did you get there? Where are you going? What do you care about? What can you teach us? That's cultural cartography.

As a Media Analytics Expert and Publisher of BuzzFeed, Dao Nguyen thinks about how media spreads online and the technology and data that publishers can use to understand why. Dao Nguyen is the Publisher of BuzzFeed, a reinvention of the traditional title in which she oversees the company’s tech, product, data and publishing platform, as well as ad product, pricing, and distribution. Nguyen joined BuzzFeed in 2012 and has been instrumental in its rapid growth as the largest independent digital media company in the world

This is an extract from a 2017 talk delivered by Dao Nguyen entitled "What Makes Something Go Viral?" delivered at TedNYC, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

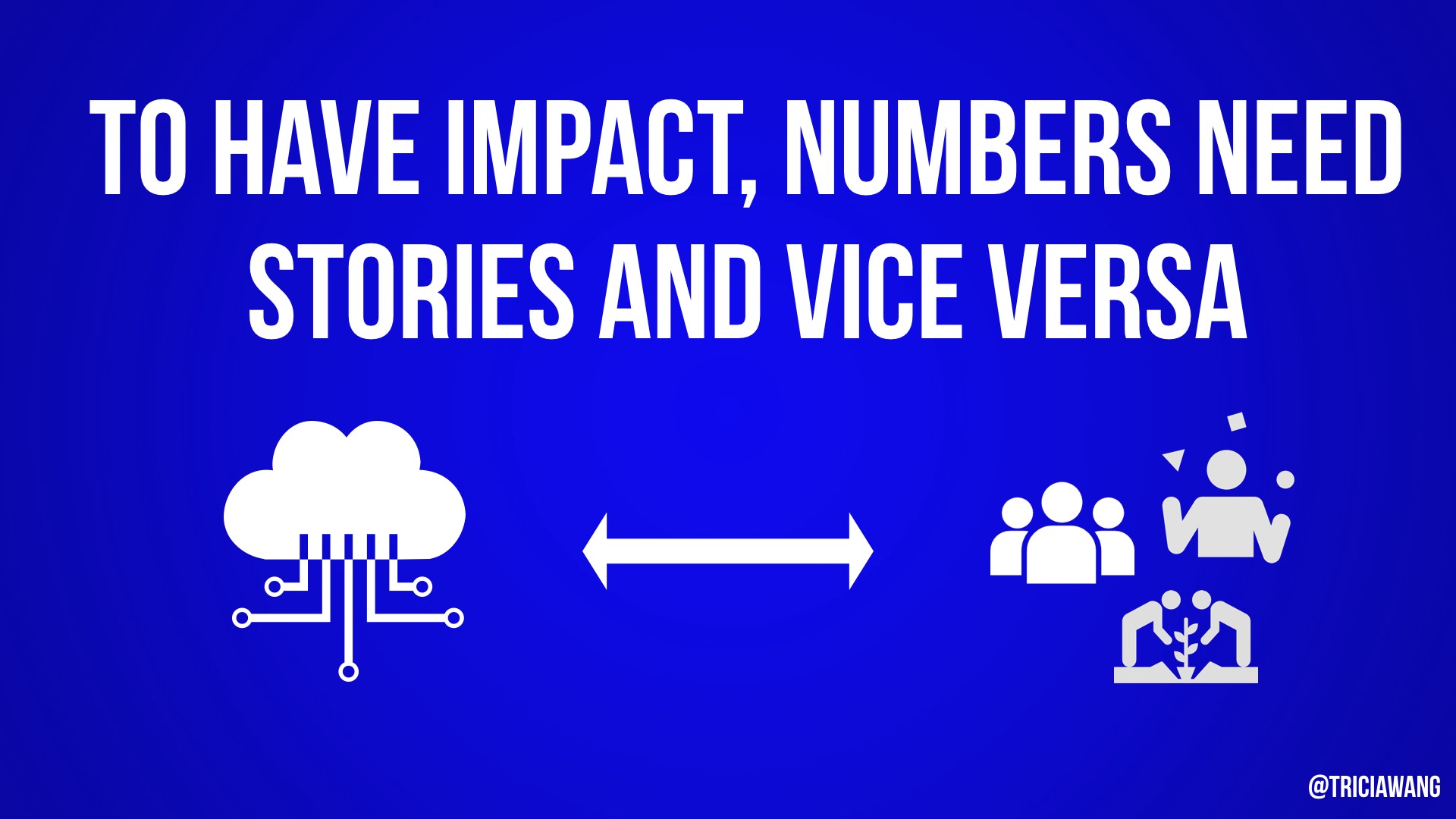

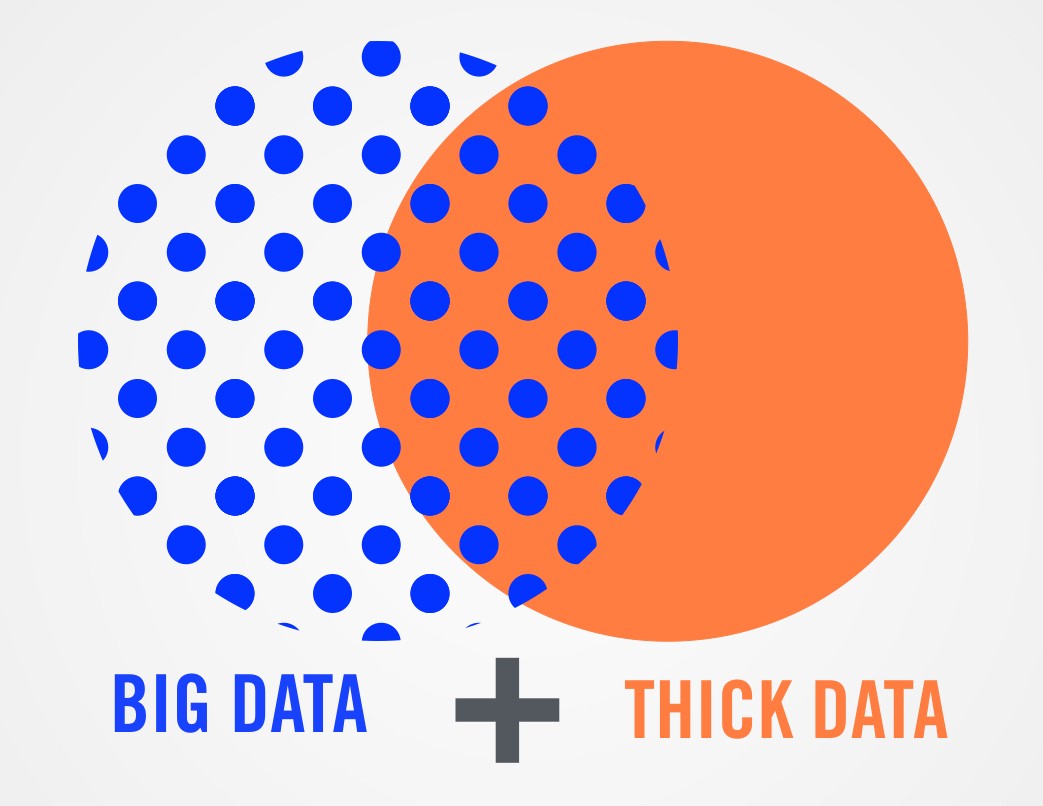

The human insights missing from Big Data

Thick data grounds our business questions in human questions, and that's why integrating big and thick data forms a more complete picture. Big data is able to offer insights at scale and leverage the best of machine intelligence, whereas thick data can help us rescue the context loss that comes from making big data usable, and leverage the best of human intelligence. And when you actually integrate the two, that's when things get really fun, because then you're no longer just working with data you've already collected. You get to also work with data that hasn't been collected. You get to ask questions about why: Why is this happening?

By Tricia Wang

In ancient Greece, when anyone from slaves to soldiers, poets and politicians, needed to make a big decision on life's most important questions, like, "Should I get married?" or "Should we embark on this voyage?" or "Should our army advance into this territory?" they all consulted the oracle.

So this is how it worked: you would bring her a question and you would get on your knees, and then she would go into this trance. It would take a couple of days, and then eventually she would come out of it, giving you her predictions as your answer.

From the oracle bones of ancient China to ancient Greece to Mayan calendars, people have craved for prophecy in order to find out what's going to happen next. And that's because we all want to make the right decision. We don't want to miss something. The future is scary, so it's much nicer knowing that we can make a decision with some assurance of the outcome.

Photo credit: Merrill College of Journalism Press Releases on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC

Well, we have a new oracle, and it's name is big data, or we call it "Watson" or "deep learning" or "neural net." And these are the kinds of questions we ask of our oracle now, like, "What's the most efficient way to ship these phones from China to Sweden?" Or, "What are the odds of my child being born with a genetic disorder?" Or, "What are the sales volume we can predict for this product?"

Now, despite the size of this industry, the returns are surprisingly low. Investing in big data is easy, but using it is hard. Over 73 percent of big data projects aren't even profitable, and I have executives coming up to me saying, "We're experiencing the same thing. We invested in some big data system, and our employees aren't making better decisions. And they're certainly not coming up with more breakthrough ideas."

This is all really interesting to me, because I'm a technology ethnographer. I study and I advise companies on the patterns of how people use technology, and one of my interest areas is data. So, why is having more data not helping us make better decisions, especially for companies who have all these resources to invest in these big data systems? Why isn't it getting any easier for them?

I've witnessed the struggle firsthand. In 2009, I started a research position with Nokia. And at the time, Nokia was one of the largest cell phone companies in the world, dominating emerging markets like China, Mexico and India -- all places where I had done a lot of research on how low-income people use technology. And I spent a lot of extra time in China getting to know the informal economy. I did things like working as a street vendor selling dumplings to construction workers. Or I did fieldwork, spending nights and days in internet cafés, hanging out with Chinese youth, so I could understand how they were using games and mobile phones and using it between moving from the rural areas to the cities.

Big Data Didn't Predict the Mass Adoption of the SmartPhone in China

I've witnessed the struggle firsthand. In 2009, I started a research position with Nokia. And at the time, Nokia was one of the largest cell phone companies in the world, dominating emerging markets like China, Mexico and India -- all places where I had done a lot of research on how low-income people use technology. And I spent a lot of extra time in China getting to know the informal economy. I did things like working as a street vendor selling dumplings to construction workers. Or I did fieldwork, spending nights and days in internet cafés, hanging out with Chinese youth, so I could understand how they were using games and mobile phones and using it between moving from the rural areas to the cities.

“So why is having more data not helping us make better decisions, especially for companies who have all these resources to invest in big data systems?”

Through all of this qualitative evidence that I was gathering, I was starting to see so clearly that a big change was about to happen among low-income Chinese people. Even though they were surrounded by advertisements for luxury products like fancy toilets -- who wouldn't want one? -- and apartments and cars, through my conversations with them, I found out that the ads the actually enticed them the most were the ones for iPhones, promising them this entry into this high-tech life. And even when I was living with them in urban slums, I saw people investing over half of their monthly income into buying a phone, and increasingly, they were "shanzhai," which are affordable knock-offs of iPhones and other brands. They're very usable. Does the job.

And after years of living with migrants and working with them and just really doing everything that they were doing, I started piecing all these data points together -- from the things that seem random, like me selling dumplings, to the things that were more obvious, like tracking how much they were spending on their cell phone bills. And I was able to create this much more holistic picture of what was happening. And that's when I started to realize that even the poorest in China would want a smartphone, and that they would do almost anything to get their hands on one.

You have to keep in mind, iPhones had just come out, it was 2009, so this was, like, eight years ago, and Androids had just started looking like iPhones. And a lot of very smart and realistic people said, "Those smartphones -- that's just a fad. Who wants to carry around these heavy things where batteries drain quickly and they break every time you drop them?" But I had a lot of data, and I was very confident about my insights, so I was very excited to share them with Nokia.

But Nokia was not convinced, because it wasn't big data. They said, "We have millions of data points, and we don't see any indicators of anyone wanting to buy a smartphone, and your data set of 100, as diverse as it is, is too weak for us to even take seriously." And I said, "Nokia, you're right. Of course you wouldn't see this, because you're sending out surveys assuming that people don't know what a smartphone is, so of course you're not going to get any data back about people wanting to buy a smartphone in two years. Your surveys, your methods have been designed to optimize an existing business model, and I'm looking at these emergent human dynamics that haven't happened yet. We're looking outside of market dynamics so that we can get ahead of it." Well, you know what happened to Nokia? Their business fell off a cliff. This -- this is the cost of missing something. It was unfathomable.

But Nokia's not alone. I see organizations throwing out data all the time because it didn't come from a quant model or it doesn't fit in one. But it's not big data's fault. It's the way we use big data; it's our responsibility. Big data's reputation for success comes from quantifying very specific environments, like electricity power grids or delivery logistics or genetic code, when we're quantifying in systems that are more or less contained.

But not all systems are as neatly contained. When you're quantifying and systems are more dynamic, especially systems that involve human beings, forces are complex and unpredictable, and these are things that we don't know how to model so well. Once you predict something about human behavior, new factors emerge, because conditions are constantly changing. That's why it's a never-ending cycle. You think you know something, and then something unknown enters the picture. And that's why just relying on big data alone increases the chance that we'll miss something, while giving us this illusion that we already know everything.

And what makes it really hard to see this paradox and even wrap our brains around it is that we have this thing that I call the quantification bias, which is the unconscious belief of valuing the measurable over the immeasurable. And we often experience this at our work. This is a very appealing message, because there's nothing wrong with quantifying; it's actually very satisfying. I get a great sense of comfort from looking at an Excel spreadsheet, even very simple ones.

image: Mark Smiciklas at Intersection Consulting

But the problem is that quantifying is addictive. And when we forget that and when we don't have something to kind of keep that in check, it's very easy to just throw out data because it can't be expressed as a numerical value. It's very easy just to slip into silver-bullet thinking, as if some simple solution existed. Because this is a great moment of danger for any organization, because oftentimes, the future we need to predict -- it isn't in that haystack, but it's that tornado that's bearing down on us outside of the barn. There is no greater risk than being blind to the unknown. It can cause you to make the wrong decisions. It can cause you to miss something big.

But we don't have to go down this path. It turns out that the oracle of ancient Greece holds the secret key that shows us the path forward. Now, recent geological research has shown that the Temple of Apollo, where the most famous oracle sat, was actually built over two earthquake faults. And these faults would release these petrochemical fumes from underneath the Earth's crust, and the oracle literally sat right above these faults, inhaling enormous amounts of ethylene gas, these fissures.

It's all true, and that's what made her babble and hallucinate and go into this trance-like state. She was high as a kite!

The Oracle by Camillo Miola

So how did anyone -- How did anyone get any useful advice out of her in this state? Well, you see those people surrounding the oracle? You see those people holding her up, and you see that guy on your left-hand side holding the orange notebook? Well, those were the temple guides, and they worked hand in hand with the oracle. When inquisitors would come and get on their knees, that's when the temple guides would get to work, because after they asked her questions, they would observe their emotional state, and then they would ask them follow-up questions, like, "Why do you want to know this prophecy? Who are you? What are you going to do with this information?" And then the temple guides would take this more ethnographic, this more qualitative information, and interpret the oracle's babblings.

So the oracle didn't stand alone, and neither should our big data systems.

Now to be clear, I'm not saying that big data systems are huffing ethylene gas, or that they're even giving invalid predictions. The total opposite. But what I am saying is that in the same way that the oracle needed her temple guides, our big data systems need them, too. They need people like ethnographers and user researchers who can gather what I call thick data. This is precious data from humans, like stories, emotions and interactions that cannot be quantified. It's the kind of data that I collected for Nokia that comes in in the form of a very small sample size, but delivers incredible depth of meaning.

And what makes it so thick and meaty is the experience of understanding the human narrative. And that's what helps to see what's missing in our models. Thick data grounds our business questions in human questions, and that's why integrating big and thick data forms a more complete picture. Big data is able to offer insights at scale and leverage the best of machine intelligence, whereas thick data can help us rescue the context loss that comes from making big data usable, and leverage the best of human intelligence. And when you actually integrate the two, that's when things get really fun, because then you're no longer just working with data you've already collected. You get to also work with data that hasn't been collected. You get to ask questions about why: Why is this happening?

“Thick data grounds our business questions in human questions, and that’s why integrating big and thick data forms a more complete picture”

Now, when Netflix did this, they unlocked a whole new way to transform their business. Netflix is known for their really great recommendation algorithm, and they had this $1 million prize for anyone who could improve it. And there were winners. But Netflix discovered the improvements were only incremental. So to really find out what was going on, they hired an ethnographer, Grant McCracken, to gather thick data insights. And what he discovered was something that they hadn't seen initially in the quantitative data. He discovered that people loved to binge-watch. In fact, people didn't even feel guilty about it. They enjoyed it.

So Netflix was like, "Oh. This is a new insight." So they went to their data science team, and they were able to scale this big data insight in with their quantitative data. And once they verified it and validated it, Netflix decided to do something very simple but impactful. They said, "instead of offering the same show from different genres or more of the different shows from similar users, we'll just offer more of the same show. We'll make it easier for you to binge-watch." And they didn't stop there. They did all these things to redesign their entire viewer experience, to really encourage binge-watching. It's why people and friends disappear for whole weekends at a time, catching up on shows like "Master of None." By integrating big data and thick data, they not only improved their business, but they transformed how we consume media. And now their stocks are projected to double in the next few years.

But this isn't just about watching more videos or selling more smartphones. For some, integrating thick data insights into the algorithm could mean life or death, especially for the marginalized. All around the country, police departments are using big data for predictive policing, to set bond amounts and sentencing recommendations in ways that reinforce existing biases. NSA's Skynet machine learning algorithm has possibly aided in the deaths of thousands of civilians in Pakistan from misreading cellular device metadata. As all of our lives become more automated, from automobiles to health insurance or to employment, it is likely that all of us will be impacted by the quantification bias.

Now, the good news is that we've come a long way from huffing ethylene gas to make predictions. We have better tools, so let's just use them better. Let's integrate the big data with the thick data. Let's bring our temple guides with the oracles, and whether this work happens in companies or nonprofits or government or even in the software, all of it matters, because that means we're collectively committed to making better data, better algorithms, better outputs and better decisions. This is how we'll avoid missing that something.

With astronaut eyes and ethnographer curiosity, Tricia Wang helps corporations grow by discovering the unknown about their customers. She has taught global organizations how to identify new customers and markets hidden behind their data, amplified IDEO's design thinking practice as an expert-in-residence, researched the social evolution of the Chinese internet, and written about the "elastic self," an emergent form of interaction in a virtual world. Wang is the co-founder of Sudden Compass, a consulting firm that helps companies unlock new growth opportunities by putting customer obsession into practice.

This is an extract from a 2016 talk delivered by Tricia Wang entitled "The Human Insights Missing from Big Data" delivered at TedxCambridge, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

The 5 types of influencers you should work with

For the past two years Treeshake has helped Water Advocate Mina Guli get her message out online. For the launch of her latest campaign, Running Dry, we gained the support of influential leaders on social media to reach over 18m people online in a day . Here's how we did it.

Influencer marketing can be one of the most powerful ways to get people interested in an issue. Simply put, it's about getting people of influence to speak about your brand. But it's more than a tactic - considerations include making sure your campaign is actually worth talking about, and then making sure you involve the right influencers.

That's where our 5 types of influencers comes in. Most of the discussion about influencers is about a) number of followers, b) levels of engagement, and c) topic relevance. However, in practice we found that there's not ONE kind of influencer that's right for a campaign - there are FIVE. Namely, Pioneers, Amplifiers, Authorities, Participators, and Scalers.

We've shied away from the typical industry language of "brand influencers", "micro-influencers", "influencers", and "celebs" because those specifically refer to number of followers rather than the role the influencer plays in a campaign.

To illustrate how we work with these influencers, and explain the categories we'll use a live campaign example...

On World Water Day , 24th March 2018, Water Advocate Mina Guli announced that she will be running 100 marathons in 100 days for 1 reason: Water. We were tasked with getting this announcement out on social media, and ensuring that her message of water conservation came through as clearly as the message of ultra endurance inspiration.

Using our Social Media Fireworks approach, we reached over 18 million people. But as you'll see in this post, it is not only that we reached LOTS of people, it is that we were joined by the RIGHT people. Some of the most influential and credible players in the space of water conservation, sport, and business supported the launch on World Water Day by mentioning Mina's campaign directly as well as the #everydropcounts hashtag.

Here are the 5 types of influencers we message and try to involve when we do a Social Media Firework:

Pioneers

The first type of influencer we’re looking at are the Pioneers -- the cool people, the front-runners. Pioneers are plugged into the scene, they're passionate about the issues.

The idea is to let these people in on the campaign as early as possible. You may even get some good ideas from your Pioneers that will improve your message.

Ok folks - this is, as ever, another impressive effort by the amazing @minaguli . I have rarely met someone more committed to water. Go Mina!! #everydropcounts https://t.co/kTMFY8ia3I

— Giulio Boccaletti (@G_Boccaletti) March 22, 2018

By 2030 humanity will be short of water by 40%. @minaguli is running 100 marathons in 100 days to raise awareness.

— Aejaz Khan (@dotkhan) March 25, 2018

In relation to the RunningDry campaign, the Pioneer Influencers we reached out to were fellow water activists and users whose feeds consisted largely of water-related content. For RunningDry, we were lucky enough to be building on the #Run4Water campaign, where we spent months ensuring Mina was following the key Pioneers in the water crisis conversation, and often getting reciprocal follows as a result. This allowed the pioneer outreach for the RunningDry launch to be carried out a lot more easily, because we could simply look through Mina’s followers for the pioneer influencers, reach out to them via DM and often have their support based on this already existing relationship.

Amplifiers

The next type of influencer to consider is the Amplifier -- they are are interested in your topic, and have a high number of engaged followers. Generally called "Influencers" they often drive the highest volume of engagement and reach in a campaign. Generally speaking their following is in the range of 100k - 1m but just as important as their large reach is their clout as conversation leaders online (you can tell by their engagement rates generally).

The amazing @minaguli is an inspiration! @YGLvoices @CityofCT #EveryDropCounts 💦 https://t.co/Ej0DjKVGgW

— Lindiwe Mazibuko (@LindiMazibuko) March 22, 2018

"If water is life, surely water scarcity — which is going to affect all of us — should be on the front page." — @minaguli on why she started @Thirst4Water 💧 #WorldWaterDay pic.twitter.com/NMEfZjvEiz

— AM to DM by BuzzFeed News (@AM2DM) March 22, 2018

Authorities

Authorities bring an added level of trust and credibility to a campaign. We're talking about institutions like universities, leading non-profits in the space, academics, and experts on the topic.

Wow, stay hydrated. Go Mina!

— Peter Gleick (@PeterGleick) March 22, 2018

Good luck! Stay hydrated. Get in touch when you are done. https://t.co/9hInKl4IL1

— Seth M. Siegel (@SethMSiegel) March 24, 2018

For Running Dry our Authority outreach included accounts like the verified World Resources, to individual gatekeepers such as Seth Siegel, author of Let There Be Water. Their participation showed people that Mina is a trusted and credible campaigner in the space of water conservation.

Participators

Participators comprise the largest proportion of your followers. They are the people who choose to follow you simply because they like your content or what you're talking about. On aggregate, participators can be the most influential of everyone in your campaign. To gain the support of Participators you need to maintain a consistently high level of relevance and entertainment value. It also really helps to activate their involvement using other channels, such as email newsletters or calls for involvement on TV and radio interviews. And of course, acknowledge and thank people for getting involved and supporting - like posts, comment back, share.

Thanks for the moderate "impractical", Stephen. Generally, it's met with "mad" "impossible" ... but this is my 100%, all in 💧🌎

— Mina Guli (@minaguli) March 22, 2018

So right, Jenine, that's why I'm giving my all. 100% commitment: 100 marathons 100 days because #EveryDropCounts now

— Mina Guli (@minaguli) March 22, 2018

Scalers

The Scalers are Celebs with mega-reach because of their huge follower counts. Even a simple share or retweet from them can be a major boost. Having their support helps you take your campaign into the mainstream.

Relatively light engagement from celebrities including Maria Sharapova, Karen Davila, and Don Riddell brought the campaign into millions of people's timelines. These were unpaid endorsements based on the strength of Mina's story and the importance of her message.

Incredible. 👊🏻🙌🏻 https://t.co/VYQ7omHYIU

— Maria Sharapova (@MariaSharapova) March 22, 2018

It’s #WorldWaterDay! Please check out my friend @minaguli’s page! She has run the world - giving attention to the water crisis! 💦💦 https://t.co/R2kRRF4XpE

— Karen Davila (@iamkarendavila) March 22, 2018

Online and Offline Influence

Lastly, Mainstream Media and Social Media are a great compliment. It's always encouraging for news organisations to see that an issue is gaining traction online. So thanks to supporters like CNN's Don Riddel and Al Arabiya's Talal Al Haj, Mina's story was carried off social media and into millions of homes around the world by broadcast television.

Diplomatic Avenue - @MinaGuli talks to Al Arabiya's @TalalAlhaj on why she is running 100 marathons in 100 days to raise awareness regarding #watercrisis https://t.co/ccMqdoYt08 pic.twitter.com/bGKoNkD77D

— Al Arabiya English (@AlArabiya_Eng) March 31, 2018

Highlighting the perilous state of our global water supply, the amazing @minaguli is planning 100 Marathons in 100 Days: https://t.co/RN1RGc5wnP

— Don Riddell (@donriddellCNN) March 26, 2018

Technology isn’t the most disruptive force of change in the world

In this devastatingly powerful piece best Selling Author of The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism Jeremy Rifkin puts the digital transformation in perspective. It's not that technology is not important, it's that we don't realise how important it is.

I’m going to start on a very sombre note. I hope at the end it will be somewhat of a liberating reflection. GDP is slowing all over the world. Productivity is on the decline.

Unemployment is up. Economists are projecting 20 more years of low productivity, and slow growth.

If we think about the industrial revolutions we’ve had, half the human race are much better off than before. The other half still haven’t caught up. The wealth of the top 8 wealthiest people in the world equals the accumulated wealth of one half of the human population - 3.5 billion people. There’s clearly something wrong with how we’re organising the economic family. There’s nothing like this in history.

This economic crisis, which is structural, has given rise to a much more profound environmental crisis.

We’ve had 3 industrial revolutions, all based on digging up the burial grounds of the carboniferous era and turning it into this civilisation, and we have spewed massive amounts of CO2, Methane, and Nitrous Oxide into the atmosphere. We’re now in real-time climate change. This is not a theory, it’s not imminent, it’s not on the horizon. It’s in the house.

Source: NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies

What’s terrifying about Climate Change that isn’t often explained clearly is this: Climate Change changes the water cycles of the earth. That’s what this is all about. We’re the watery planet. It’s never explained, and if it were, every parent and grandparent and teacher would be driven with one purpose and one agenda: to save our species in the next 7 decades.

Our ecosystems have developed over millions of years based on the water cycles, the clouds that traverse our ecosystems. Here’s the rub: for every 1 degree our temperature goes up, the atmosphere is sucking up 7% more precipitation from the ground. The heat causes that. The water precipitates into the clouds quicker so we’re getting more concentrated precipitation - more violent water events- and also unpredictable.

The Spring floods we've seen the US in the Carolina’s are supposedly one in a thousand year events - they’ve had 6 in the past 2 and a half years. We're seeing more dramatic and prolonged droughts and wildfires [as experienced in the Western Cape of South Africa]. We’ve got category 3, 4, and 5 hurricanes. The one that hit the Philippines last year was the most powerful ever recorded. This is the new normal.

And because the freshwater melts from the Arctic and Antarctica are moving so quickly, the water currents in our great oceans are on an exponential runaway curve. We are expecting storms on an unprecedented level in the coming decades that have never been seen by humans on this planet. Infrastructure will be destroyed and lives will be lost.

Our scientists now tell us we’re on the 6th mass extinction event of life on planet earth, and it doesn’t even make headlines. We’ve had 5 mass extinction events on earth in the past 450million years, well before humans even showed up. And when they happened, they happened quickly. There’s always this tipping point in the chemistry of the planet, then massive die-out. On the average, it took 10 million years to get life back on earth after the die-out.

Our scientists tell us we’re on the 6th extinction event. We’re chronicling it, it’s not a model. And we’re being told we’re going to lose upwards of 50% of all the life-forms on Earth likely in the next 8 decades. The last time this happened was 65 million years ago. But then it took thousands of years. This is 8 decades. This is a wipe-out.

We’re just not taking in the enormity of this. We’re greenwashing. We’re going on with business as usual. This is one of 20 issues. No. This is about Extinction. This is about survival.

99.5% of species of life that have ever been on this little planet have come, and gone. Actuarially speaking those are not good odds. Humans are the youngest species, we’ve been here just 200 thousand years. We’re the babies. There’s no guarantee we’re gonna make it.

So what do we do?

We need a new economic vision for the world, and it needs to be compelling. We need a game-plan to deploy that vision. It needs to be quick. It has to move as quickly in the developing world as the industrialised world. We need to be off the carbon-based civilisation. Off. OFF in less than four decades. If we want to have any chance of at least avoiding the abyss, it’s about adaptation, resiliency, and later on about regeneration.

Jeremy Rifkin

Jeremy Rifkin is the author of The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism and The Third Industrial Revolution: How Lateral Power is Transforming Energy, the Economy, and the World. Mr. Rifkin is an advisor to the European Union and to heads of state around the world, and president of the Foundation on Economic Trends in Washington, DC.

This is an extract from a talk by Jeremy Rifkin entitled "A history of the future – the world in 2025" delivered at the European Central Bank, published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence

Dave Duarte on How to Grow a Social Movement

In his talk Dave shares some of the methods that we at Treeshake have used to run campaigns that have reached over 1b people this year.

Last month, Treeshake founder Dave Duarte spoke at Think Future, a gathering of 233 participants from 20 countries who all work in the field of early childhood development.

In the video below Dave shares some of the methods that we at Treeshake have used to run campaigns with a combined reach of over 1 billion this year.

Video by Innovation Edge, Nov 2017

You can download the slides to follow along with the presentation here (3mb .pdf)

What is Social Currency? Why do you need it, and how you get more of it?

You know what's cool? Social Currency is cool. Social Currency is what you have when you participate in a hot topic and contribute valuable discussion points. It's what you have when you discover some juicy gossip before anyone else. Social currency is knowing something that others want to know. It's relevance that you can exchange for benefits ranging from money to esteem to friendship and more.

You know what's cool? Social Currency is cool. Social Currency is what you have when you participate in a hot topic and contribute valuable discussion points. It's what you have when you discover some juicy gossip before anyone else. Social currency is knowing something that others want to know. It's relevance that you can exchange for benefits ranging from money to esteem to friendship and more.

The paradox of social currency is that the more you share it, the more you have it. The trick is: it's time sensitive. You need to share your currency when people are most likely to find it interesting, and that is increasingly as it happens.

To see social currency in action, go to Twitter and have a look at the trending news topics. On every topic people are sharing memes and insights to the discussion. What do they get from it? Social Currency. But it doesn't spread evenly, here the Matthew Effect applies: "to those who have shall be given more"

Fashion is also a form of social currency. A look is hot for a small time, and if you get onto the trend early you benefit the most from it. Fashion through the lens of a sociologist is basically a conversation - it's showing that you're plugged into the stream of coolness and style.

According to Wikipedia, the concept of social currency derives from Pierre Bourdieu's social capital theory and relates to increasing one's sense of community, granting access to information and knowledge, helping to form one's identity, and providing status and recognition.

Social Currency is one of the primary reasons why content spreads online. Jonah Berger, who has spent a decade investigating what makes things go viral, says there are 6 principles of virality (STEPPS):

Social currency – we share what makes us look good.

Triggers – we share what’s at the top of our minds.

Emotion – we share what we care about.

Public – we imitate what we see people around us are doing.

Practical value – we share things that have value to others.

Stories – We share stories, not information.

How do you get more of it?

Gathering social currency is not just about sources of information, it is about your own skills and ability to make sense of the information you get and share it with panache. As with most things social, you need to develop momentum - developing habits and systems to feed you fresh insight, developing trusted sources, and growing your following as you interpret the info you get.

Some practical tips:

- participate in live events and conferences where thought-leaders and pioneers are speaking and attending.

- curate your news feeds for relevant insight

- participate in Twitter trending topics and see how much traction you can get with your commentary.

The Matthew Effect in Social Media

Famous for being famous. New followers because you have so many already. To those who have shall be given more. A social power law we can see playing out all day every day.

Why do seemingly inane videos like "Charlie Bit My Finger" have SO MANY views? It's the Matthew Effect in action.

Famous for being famous. New followers because you have so many already. To those who have shall be given more.

We call this the Matthew Effect. From the Bible:

For whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them. — Matthew 25:29

Algorithms tend to favour already-popular content. And we already know how persuasive popularity is.

Via Wikipedia:

In the sociology of science, "Matthew effect" was a term coined by Robert K. Merton to describe how, among other things, eminent scientists will often get more credit than a comparatively unknown researcher, even if their work is similar; it also means that credit will usually be given to researchers who are already famous. For example, a prize will almost always be awarded to the most senior researcher involved in a project, even if all the work was done by a graduate student. This was later formulated by Stephen Stigler as Stigler's law of eponymy — "No scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer" — with Stigler explicitly naming Merton as the true discoverer, making his "law" an example of itself.

Merton furthermore argued that in the scientific community the Matthew effect reaches beyond simple reputation to influence the wider communication system, playing a part in social selection processes and resulting in a concentration of resources and talent. He gave as an example the disproportionate visibility given to articles from acknowledged authors, at the expense of equally valid or superior articles written by unknown authors. He also noted that the concentration of attention on eminent individuals can lead to an increase in their self-assurance, pushing them to perform research in important but risky problem areas.

So How Do You Beat the Matthew Effect

The Matthew Effect is not something you can beat, it's something you can use. Unfortunately it's true that it is harder to gain attention when you start. But it is also your best opportunity to be Surprising.

This is why we work with the Hot Content model to develop social momentum.