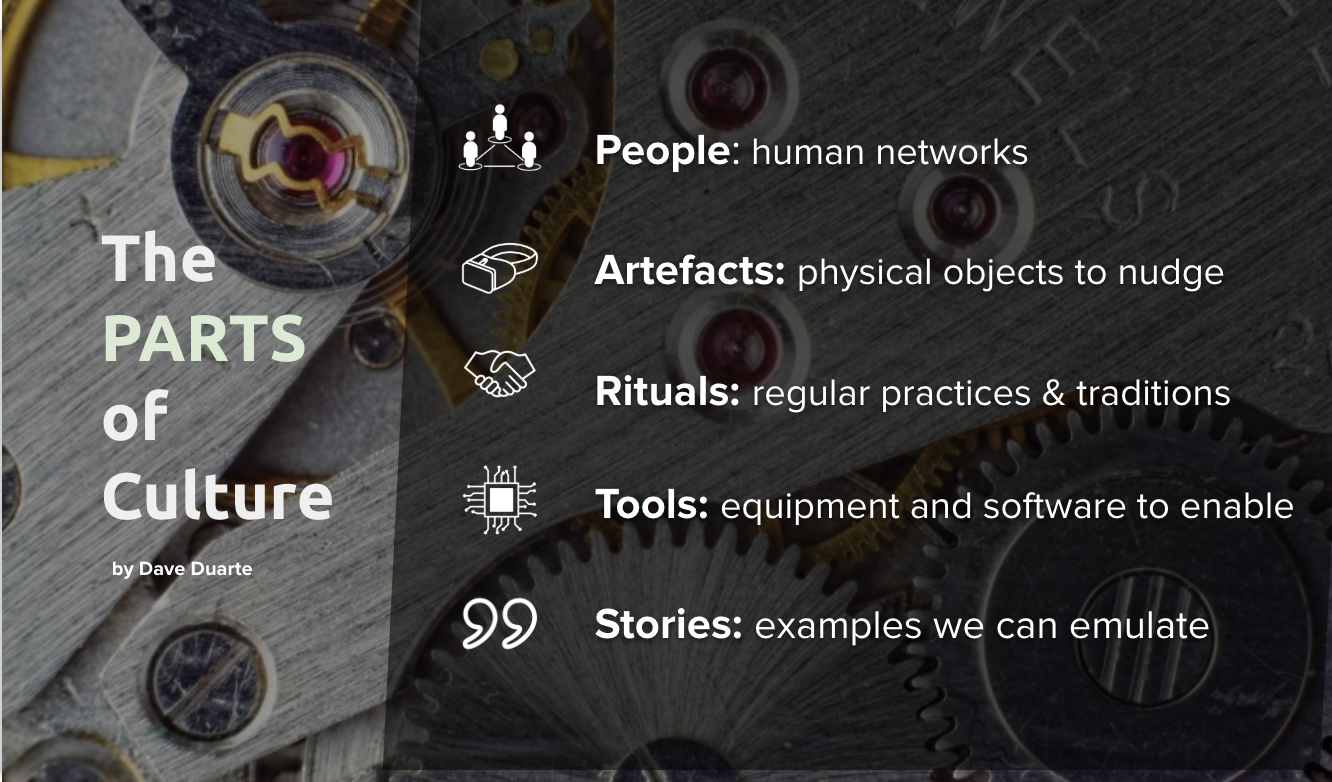

PARTS: The 5 working parts of company culture

Every good leader knows the importance of Company Culture, and yet it is difficult to grasp and actively shape. Culture determines a groups capability to respond to change, and to function as more than the sum of its parts. To help get a handle on this seemingly intangible concept let us introduce you to the PARTS of culture.

By Dave Duarte

Culture is the hidden force that shapes our decision-making day to day, what we value, and how we get things done. And yet culture isn’t something that can be set in place, it is emergent and adapts.

The PARTS of Culture provides an memorable framework to work with when aiming to influence culture. It stands for People, Artefacts, Rituals, Tools, and Stories.

A bit of background

When we launched the OgilvyDMA in 2010, Rob Hill and Gavin Levinsohn said our primary objective was to help "geekify" the Ogilvy Cape Town culture. Now, "Changing Culture" sounds all well and good, but when it came to it I had no idea where to start. I turned to sociological theory on culture for clarity, and out of that developed PARTS as a way to make the key concepts memorable and strategically actionable.

Here’s more details on each of these aspects, and how we applied them with remarkable success at Ogilvy.

People: gain the support of a few well connected people, and help them recruit others

Too many companies make the mistake of trying to change the whole company at once. You’re more likely to gain traction incubating culture among a group of influential people who have provide reach and access to the rest of the organisation.

Behaviours spread from person to person (Christakis, 2007). So it's important to work with a small group of people initially to make sure the cultural change is understood and adapted.

The key players in a social network are your Experts, Influencers, Gatekeepers, and Connectors. Each are important in their own ways, and you need to gain their support for any culture change initiative. These people need to have a high frequency of contact with the cultural change process an practice. They are going to be the ones that set the example and distribute the culture to the rest of the organisation. As Derek Sivers famously put it "new followers don't follow the leader, they follow the other followers."

At Ogilvy, the most influential people throughout the agency were invited to our first Ogilvy Digital Marketing Academy, and no expense was spared in ensuring a transformative learning experience that created group buy-in and connection.

Artefacts: make the culture change public and visible

Our physical environment and the objects in it form the stage on which your staff perform. Are you setting them up for great performances, giving them the cues and props they need? Art, Awards, and artefacts of belonging (like lapel pins, t-shirts, certificates) all serve to communicate cultural values.

Open Knowledge Foundation, "OPEN" lapel pin, by Brian Glanz

Amazon, for example, reminds people of their value of frugality through the use of door-desks throughout the company.

Ogilvy encouraged more a more digitally savvy culture by making the latest gadgets available to staff through Ogilvy Labs. There are screens live-streaming social data from clients, there are interactive demos of the latest in sensory technology around the office, and there are framed certificates displayed for people who complete digital training. Other artefacts could include the kinds of awards that are valued, for example, displaying Cannes Lions, or Bookmark Awards.

Rituals: Go from a moment to a movement

The things a company does regularly become a signal of their culture. The rituals can be small or large, everything from how you on-board staff to how you handle daily meetings.

The key thing when you want to introduce a ritual is to do it consistently and repeatedly. It takes time for new behaviours to take root. Your company values aren’t just things that you just write down and forget about, they should be reflected in what behaviours you reward. In who you hire, promote and let go. These create behavioural norms that become embedded in your company culture.

For example, Ogilvy hosts a regular “How-To Friday” session where people who have done something extraordinary share how they did it. This signals the company’s long-term commitment to hands-on innovation.

Tools: give people the resources to create change

How do you equip your people to do their work in a way that reflects company culture? You can't expect change if you don't enable it. Language, skills, technology, equipment, and other resources are major enablers of change.

The most fundamental tool for culture-shaping is language. When you want to shift culture, equip people with new ways to talk about what they do.

A key part of the Ogilvy Digital Marketing Academy's success was, and is, giving people the language to speak about digital. Concepts like Impressions, Reach, Landing Pages, and Programmatic become more useful when we have the words to talk about them.

Story: don't just tell people about the change, show them what others are doing

Stories are the way that people naturally encode and share complex social information. There are two ways a company can bring their story to life: storytelling and storymaking.

Storytelling is about finding examples of good cultural practice and crafting stories around those actions so that it is easier for others to understand what to do, and to emulate the success of the cultural heroes you celebrate.

Storymaking is about kickstarting this process. It’s not just about what you celebrate, but also how you take action. It is about taking decisive action to establish cultural precedence.

At Ogilvy, stories were created by investing more heavily in case-studies involving digital integration, such as Be The Coach (which went on to become the most awarded campaign of the year - winning international plaudits including four Gold Lions at Cannes)

Stories are like software for the mind. They help us understand cause and effect, and can have a transformative effect on what we see as possible and expected.

The results of the first application of our PARTS model can best be summed up by Ogilvy Cape Town's Managing Director, Gavin Levinson

“What’s the best thing that’s happened in the Ogilvy ‘family’ over the past three years? While there are many highlights and accolades within and across all of Ogilvy’s companies, I would undoubtably say that the ODMA has and continues to be our finest hour.”

Treeshake offers story-making workshops and talks on culture change, leading innovation, and values-driven leadership.

If a story moves you, act on it

Stories are necessary, but they're not as magical as they seem, says writer Sisonke Msimang. In this funny and thoughtful talk, Msimang questions our emphasis on storytelling and spotlights the decline of facts. During a critical time when listening has been confused for action, Msimang asks us to switch off our phones, step away from our screens and step out into the real world to create a plan for justice.

Stories are necessary, but they're not as magical as they seem, says writer Sisonke Msimang. In this funny and thoughtful talk, Msimang questions our emphasis on storytelling and spotlights the decline of facts. During a critical time when listening has been confused for action, Msimang asks us to switch off our phones, step away from our screens and step out into the real world to create a plan for justice.

I'm here to talk about my own observations about storytelling. I want to talk to you about the power of stories, of course, but I also want to talk about their limitations, particularly for those of us who are interested in social justice.

Stories are everywhere, and if there was a danger in the telling of one tired old tale, then I think there has got to be lots to celebrate about the flourishing of so many stories and so many voices. Stories are the antidote to bias. In fact, today, if you are middle class and connected via the internet, you can download stories at the touch of a button or the swipe of a screen. You can listen to a podcast about what it's like to grow up Dalit in Kolkata. You can hear an indigenous man in Australia talk about the trials and triumphs of raising his children in dignity and in pride. Stories make us fall in love. They heal rifts and they bridge divides. Stories can even make it easier for us to talk about the deaths of people in our societies who don't matter, because they make us care. Right?

“If it is justice that we are after, then I think we mustn’t focus on the media or the storytellers. We must focus on audiences, on anyone who has ever turned on a radio or listened to a podcast, and that means all of us”

I'm not so sure, and I actually work for a place called the Centre for Stories. And my job is to help to tell stories that challenge mainstream narratives about what it means to be black or a Muslim or a refugee or any of those other categories that we talk about all the time. But I come to this work after a long history as a social justice activist, and so I'm really interested in the ways that people talk about nonfiction storytelling as though it's about more than entertainment, as though it's about being a catalyst for social action. It's not uncommon to hear people say that stories make the world a better place. Increasingly, though, I worry that even the most poignant stories, particularly the stories about people who no one seems to care about, can often get in the way of action towards social justice. Now, this is not because storytellers mean any harm. Quite the contrary. Storytellers are often do-gooders like me and, I suspect, yourselves. And the audiences of storytellers are often deeply compassionate and empathetic people. Still, good intentions can have unintended consequences, and so I want to propose that stories are not as magical as they seem.

So three -- because it's always got to be three -- three reasons why I think that stories don't necessarily make the world a better place.

Firstly,

stories can create an illusion of solidarity. There is nothing like that feel-good factor you get from listening to a fantastic story where you feel like you climbed that mountain, right, or that you befriended that death row inmate. But you didn't. You haven't done anything. Listening is an important but insufficient step towards social action.

Secondly,

I think often we are drawn towards characters and protagonists who are likable and human. And this makes sense, of course, right? Because if you like someone, then you care about them. But the inverse is also true. If you don't like someone, then you don't care about them. And if you don't care about them, you don't have to see yourself as having a moral obligation to think about the circumstances that shaped their lives.

Thirdly,

I think that stories don't necessarily make the world a better place because too often we are so invested in the personal narrative that we forget to look at the bigger picture. And so we applaud someone when they tell us about their feelings of shame, but we don't necessarily link that to oppression. We nod understandingly when someone says they felt small, but we don't link that to discrimination. The most important stories, especially for social justice, are those that do both, that are both personal and allow us to explore and understand the political.

Photo credit: recombiner

But it's not just about the stories we like versus the stories we choose to ignore.

Increasingly, we are living in a society where there are larger forces at play, where stories are actually for many people beginning to replace the news. We live in a time where we are witnessing the decline of facts, when emotions rule and analysis, it's kind of boring, right? Where we value what we feel more than what we actually know. A recent report by the Pew Center on trends in America indicates that only 10 percent of young adults under the age of 30 "place a lot of trust in the media." Now, this is significant. It means that storytellers are gaining trust at precisely the same moment that many in the media are losing the confidence in the public. This is not a good thing, because while stories are important and they help us to have insights in many ways, we need the media. From my years as a social justice activist, I know very well that we need credible facts from media institutions combined with the powerful voices of storytellers. That's what pushes the needle forward in terms of social justice.

In the final analysis, of course, it is justice that makes the world a better place, not stories. Right? And so if it is justice that we are after, then I think we mustn't focus on the media or on storytellers. We must focus on audiences, on anyone who has ever turned on a radio or listened to a podcast, and that means all of us.

So a few concluding thoughts on what audiences can do to make the world a better place:

- The world would be a better place, I think, if audiences were more curious and more skeptical and asked more questions about the social context that created those stories that they love so much.

- The world would be a better place if audiences recognized that storytelling is intellectual work. And I think it would be important for audiences to demand more buttons on their favorite websites, buttons for example that say, "If you liked this story, click here to support a cause your storyteller believes in." Or "click here to contribute to your storyteller's next big idea." Often, we are committed to the platforms, but not necessarily to the storytellers themselves.

- I think that audiences can make the world a better place by switching off their phones, by stepping away from their screens and stepping out into the real world beyond what feels safe.

Alice Walker has said, "Look closely at the present you are constructing. It should look like the future you are dreaming."

Storytellers can help us to dream, but it's up to all of us to have a plan for justice.

Sisonke Msimang tells stories about justice and human rights. In the early part of her career, Msimang set up a fund fight for people whose health had been compromised by their race, class and gender identities. In 2008 she became the executive director of the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, responsible for making grants on human rights projects. Msimang is now the head of programs at the Centre for Stories, a new initiative that collects, preserves and shares stories about migrants, refugees and diverse people and places linked to the Indian Ocean Rim.

This is an extract from a 2016 talk delivered by Sisonke Msimang entitled "If a story moves you, act on it" delivered at TEDWomen, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

The longevity of stories

We need stories. To communicate, to understand, to relate to each other, to explain. People have, throughout time and history, incorporated storytelling (and storymaking) into their lives, because it's how we make sense of the dynamic, often complex, situations we find ourselves in. Neil Gaiman, a master storyteller, outlines the importance of a good story, and the ability stories have to shape culture and behaviour

We need stories. To communicate, to understand, to relate to each other, to explain. People have, throughout time and history, incorporated storytelling (and storymaking) into their lives, because it's how we make sense of the dynamic, often complex, situations we find ourselves in. Neil Gaiman, a master story teller, outlines the importance of a good story, and the ability stories have to shape culture and behaviour:

By Neil Gaiman

Stories aren’t books. Books are simply one of the many storage mechanisms in which stories can be kept and, obviously, people are one of the other storage mechanisms. Stories change. The professions, the media that we use to store, record and transmit stories will change. Not long ago the people who stored and transmitted information were stonemasons. Now, not so much. Unless we want the information to last.

As individuals, we are cut off from humanity. As individuals, we are naked, we do not even know which plants will kill us. Without the mass of human knowledge accumulated over millennia to buoy us up, we are in big trouble. With it, we are warm, fed, we have popcorn, we are sitting in comfortable seats and we are capable of arguing with each other about really stupid things on the internet. That's because we have stories, it's because we have information.

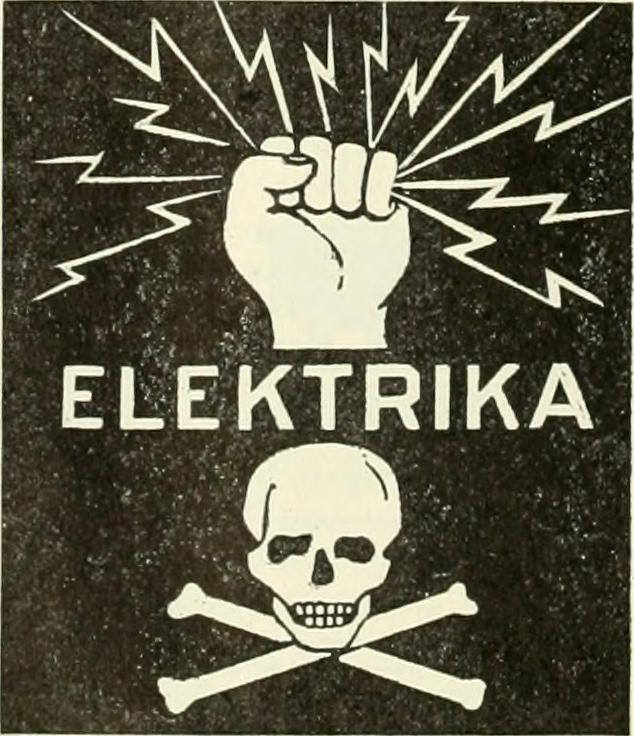

In 1984 a man, whose name I don't know how to pronounce, I think it's Thomas Sebeok, wrote a report for the Department of Energy. He was asked to create a report because they had a problem - what to do with nuclear waste repositories. They needed to devise a method of warning future generations not to mine or drill at that site unless they're aware of the other consequences of their actions… and because the stuff that they would be putting in these nuclear waste repositories had a half-life of 10000 years, they needed to figure out ways to get information to last 10000 years. They started by looking at all you can write. The trouble with writing things is that it lasts a certain amount of time, but anyone here who’s actually tried to read Beowulf in the original knows that that only takes you so far. Language changes. Words change meaning. And if language is changing, what about pictographics? What if you put a big skull up? And Thomas pointed out that even a skull means different things in different cultures - some cultures might go “ahh, skull, symbol of warning,” some might go, “symbol of fantastic candy days. This is the place where the good stuff!”.

ISO Radiation Warning Sign

What he actually came up with, he said that the prime recommendation of the Human Interference Task Force of Department of Energy was that information be launched and artificially passed down into the short-term and long-term future, with these supplementary aid of folkloristic devices, in particular a combination of artificially created and nurtured ritual and legend. The most positive aspect of such a procedure is it need not be geographically localised, or tied to any one language or culture. So, the initiated would be steered away from the hazardous site, for reasons other than the scientific knowledge of the possibility of radiation and its implications, essentially the reason would be accumulated superstition to shun a certain area permanently.

A ritual with the legend retold year by year, with presumably slight variation. The actual “truth” would be entrusted exclusively to, what we might call for dramatic emphasis, an ‘atomic priesthood’ - it is a commission of knowledgeable physicists, experts in radiation sickness, anthropologists and whatever additional expertise may be called for in the future. Folklore specialists that they’d consulted say they know of no precedent, nor could they think of a parallel situation, except the well-known but ineffectual curse is associated with the burial sites of some Egyptian Pharaohs, which didn't deter greedy grave robbers from digging for hidden treasure.

“What we can do, I think, is try and create stories that are interesting enough and important enough that our grandchildren might want to tell those stories to their grandchildren. Because that’s the purpose of stories. It’s what they’re for. ”

First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang

Terracotta Warrior

Which is true, up to a point. The first emperor of China died 2000 years ago, and the site of his tomb was lost. Very intentionally lost - he killed anybody who knew where it was. It was a magnificent act of tomb losing. And then one day, in a field in China, somebody unearthed a Terracotta Warrior. And then they found another one. They excavated warriors and archaeologists worked out very quickly where the actual mausoleum had to be. The stories that come down to us 2300 years after the emperor China at died, now became a warning. Remember those lakes of mercury? That stuff is really poisonous. It doesn't even have a half-life, it's just there. As Terry Pratchett once said, “Radiation is 10000 years, arsenic is forever,” and so they didn't immediately start digging, instead they checked, confirmed the presence of incredibly high quantities of mercury and have been figuring out what to do ever since. And when they figure out how to get in there without dying, they will start excavating.

The Long Now, and the clock of The Long Now is about planning for the long term, and thinking in the long term, in a world in which people appear to be thinking in the shorter and shorter term, not even necessarily at this point about things that will take them to the end of their lifetime, which at least at one point you would have thought, “well, you know, I'll be dead before that's a problem,” looking around now, the mess we’re making of things on his planet. You wanna go to people and say, “you know actually, you will be. You will still be around. We could run out of water, you'll be here, having to figure out what to do with no water. What to do when the oceans are screwed up. What to do when Twitter finally becomes sentient.

Tom Sebeok concluded that you couldn’t actually create a story that would last 10000 years, you could only create a story that would last a 3 Generations - for ourselves, for our children, for their children. But what we can do, I think, is try and create stories that are interesting enough and important enough that our grandchildren might want to tell those stories to their grandchildren. Because that's the purpose of stories. It's what they’re for. They make life worth living and, sometimes, they keep us alive

Neil Gaiman has told stories in every medium—graphic novels (The Sandman), novels (The Ocean at the End of the Lane; American Gods), short stories (Trigger Warning), children’s books (The Graveyard Book), television (Dr Who), and the occasional song (“I Google You”)

This is an extract from a 2015 talk delivered by Neil Gaiman entitled "How Stories Last" delivered for the Long Now Foundation, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Dave Duarte, founder of Treeshake, is passionate about community engagement as a driver of value. As social marketer, speaker, facilitator and advisor, his warm and engaging style makes the future easy to engage with. Dave brings over a decade of facilitation experience to his work at Treeshake. He has founded several businesses, and served in leadership positions in media, academia, and non-profits.