PARTS: The 5 working parts of company culture

Every good leader knows the importance of Company Culture, and yet it is difficult to grasp and actively shape. Culture determines a groups capability to respond to change, and to function as more than the sum of its parts. To help get a handle on this seemingly intangible concept let us introduce you to the PARTS of culture.

By Dave Duarte

Culture is the hidden force that shapes our decision-making day to day, what we value, and how we get things done. And yet culture isn’t something that can be set in place, it is emergent and adapts.

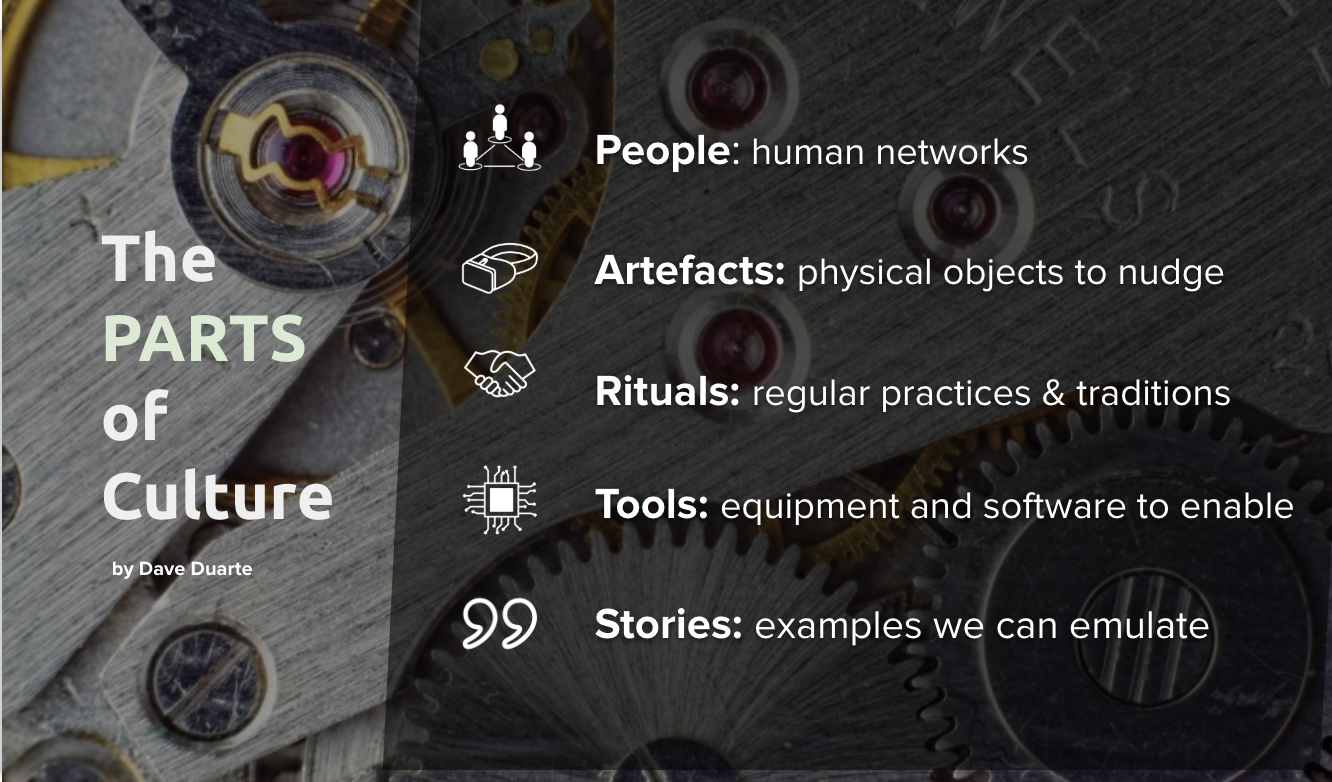

The PARTS of Culture provides an memorable framework to work with when aiming to influence culture. It stands for People, Artefacts, Rituals, Tools, and Stories.

A bit of background

When we launched the OgilvyDMA in 2010, Rob Hill and Gavin Levinsohn said our primary objective was to help "geekify" the Ogilvy Cape Town culture. Now, "Changing Culture" sounds all well and good, but when it came to it I had no idea where to start. I turned to sociological theory on culture for clarity, and out of that developed PARTS as a way to make the key concepts memorable and strategically actionable.

Here’s more details on each of these aspects, and how we applied them with remarkable success at Ogilvy.

People: gain the support of a few well connected people, and help them recruit others

Too many companies make the mistake of trying to change the whole company at once. You’re more likely to gain traction incubating culture among a group of influential people who have provide reach and access to the rest of the organisation.

Behaviours spread from person to person (Christakis, 2007). So it's important to work with a small group of people initially to make sure the cultural change is understood and adapted.

The key players in a social network are your Experts, Influencers, Gatekeepers, and Connectors. Each are important in their own ways, and you need to gain their support for any culture change initiative. These people need to have a high frequency of contact with the cultural change process an practice. They are going to be the ones that set the example and distribute the culture to the rest of the organisation. As Derek Sivers famously put it "new followers don't follow the leader, they follow the other followers."

At Ogilvy, the most influential people throughout the agency were invited to our first Ogilvy Digital Marketing Academy, and no expense was spared in ensuring a transformative learning experience that created group buy-in and connection.

Artefacts: make the culture change public and visible

Our physical environment and the objects in it form the stage on which your staff perform. Are you setting them up for great performances, giving them the cues and props they need? Art, Awards, and artefacts of belonging (like lapel pins, t-shirts, certificates) all serve to communicate cultural values.

Open Knowledge Foundation, "OPEN" lapel pin, by Brian Glanz

Amazon, for example, reminds people of their value of frugality through the use of door-desks throughout the company.

Ogilvy encouraged more a more digitally savvy culture by making the latest gadgets available to staff through Ogilvy Labs. There are screens live-streaming social data from clients, there are interactive demos of the latest in sensory technology around the office, and there are framed certificates displayed for people who complete digital training. Other artefacts could include the kinds of awards that are valued, for example, displaying Cannes Lions, or Bookmark Awards.

Rituals: Go from a moment to a movement

The things a company does regularly become a signal of their culture. The rituals can be small or large, everything from how you on-board staff to how you handle daily meetings.

The key thing when you want to introduce a ritual is to do it consistently and repeatedly. It takes time for new behaviours to take root. Your company values aren’t just things that you just write down and forget about, they should be reflected in what behaviours you reward. In who you hire, promote and let go. These create behavioural norms that become embedded in your company culture.

For example, Ogilvy hosts a regular “How-To Friday” session where people who have done something extraordinary share how they did it. This signals the company’s long-term commitment to hands-on innovation.

Tools: give people the resources to create change

How do you equip your people to do their work in a way that reflects company culture? You can't expect change if you don't enable it. Language, skills, technology, equipment, and other resources are major enablers of change.

The most fundamental tool for culture-shaping is language. When you want to shift culture, equip people with new ways to talk about what they do.

A key part of the Ogilvy Digital Marketing Academy's success was, and is, giving people the language to speak about digital. Concepts like Impressions, Reach, Landing Pages, and Programmatic become more useful when we have the words to talk about them.

Story: don't just tell people about the change, show them what others are doing

Stories are the way that people naturally encode and share complex social information. There are two ways a company can bring their story to life: storytelling and storymaking.

Storytelling is about finding examples of good cultural practice and crafting stories around those actions so that it is easier for others to understand what to do, and to emulate the success of the cultural heroes you celebrate.

Storymaking is about kickstarting this process. It’s not just about what you celebrate, but also how you take action. It is about taking decisive action to establish cultural precedence.

At Ogilvy, stories were created by investing more heavily in case-studies involving digital integration, such as Be The Coach (which went on to become the most awarded campaign of the year - winning international plaudits including four Gold Lions at Cannes)

Stories are like software for the mind. They help us understand cause and effect, and can have a transformative effect on what we see as possible and expected.

The results of the first application of our PARTS model can best be summed up by Ogilvy Cape Town's Managing Director, Gavin Levinson

“What’s the best thing that’s happened in the Ogilvy ‘family’ over the past three years? While there are many highlights and accolades within and across all of Ogilvy’s companies, I would undoubtably say that the ODMA has and continues to be our finest hour.”

Treeshake offers story-making workshops and talks on culture change, leading innovation, and values-driven leadership.

The simple trick to finding the most connected and influential people in a social network

We're all embedded in vast social networks of friends, family, co-workers and more. Nicholas Christakis tracks how a wide variety of traits can spread from person to person, showing how your location in the network might impact your life in ways you don't even know. Christakis highlights how new forms of data collection allow us to locate the central people within a network and ultimately "use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being."

We're all embedded in vast social networks of friends, family, co-workers and more. Nicholas Christakis tracks how a wide variety of traits -- from happiness to obesity -- can spread from person to person, showing how your location in the network might impact your life in ways you don't even know. Christakis highlights how new forms of data collection allow us to locate the central people within a network and ultimately "use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being."

For the last 10 years, I've been spending my time trying to figure out how and why human beings assemble themselves into social networks. And the kind of social network I'm talking about is not the recent online variety, but rather, the kind of social networks that human beings have been assembling for hundreds of thousands of years, ever since we emerged from the African savannah. So, I form friendships and co-worker and sibling and relative relationships with other people who in turn have similar relationships with other people. And this spreads on out endlessly into a distance. And you get a network that looks like this. Every dot is a person. Every line between them is a relationship between two people -- different kinds of relationships. And you can get this vast fabric of humanity, in which we're all embedded.

My colleague, James Fowler and I have been studying for quite sometime what are the mathematical, social, biological and psychological rules that govern how these networks are assembled and what are the similar rules that govern how they operate, how they affect our lives. But recently, we've been wondering whether it might be possible to take advantage of this insight, to actually find ways to improve the world, to do something better, to actually fix things, not just understand things.

So one of the first things we thought we would tackle would be how we go about predicting epidemics.

And the current state of the art in predicting an epidemic -- if you're the CDC or some other national body -- is to sit in the middle and collect data from physicians and laboratories in the field that report the prevalence or the incidence of certain conditions. These data are fed into a central repository, with some delay. And if everything goes smoothly, one to two weeks from now you'll know where the epidemic was today. And actually, about a year or so ago, there was this promulgation of the idea of Google Flu Trends, with respect to the flu, where by looking at people's searching behavior today, we could know what the status of the epidemic was today, what's the prevalence of the epidemic today.

But what I'd like to show you is a means by which we might get not just rapid warning about an epidemic, but also actually early detection of an epidemic. And, in fact, this idea can be used not just to predict epidemics of germs, but also to predict epidemics of all sorts of kinds. For example, anything that spreads by a form of social contagion could be understood in this way, from abstract ideas on the left like patriotism, or altruism, or religion to practices like dieting behavior, or book purchasing, or drinking, or products that people might buy, purchases of electronic goods, anything in which there's kind of an interpersonal spread.

A kind of a diffusion of innovation could be understood and predicted by the following mechanism.

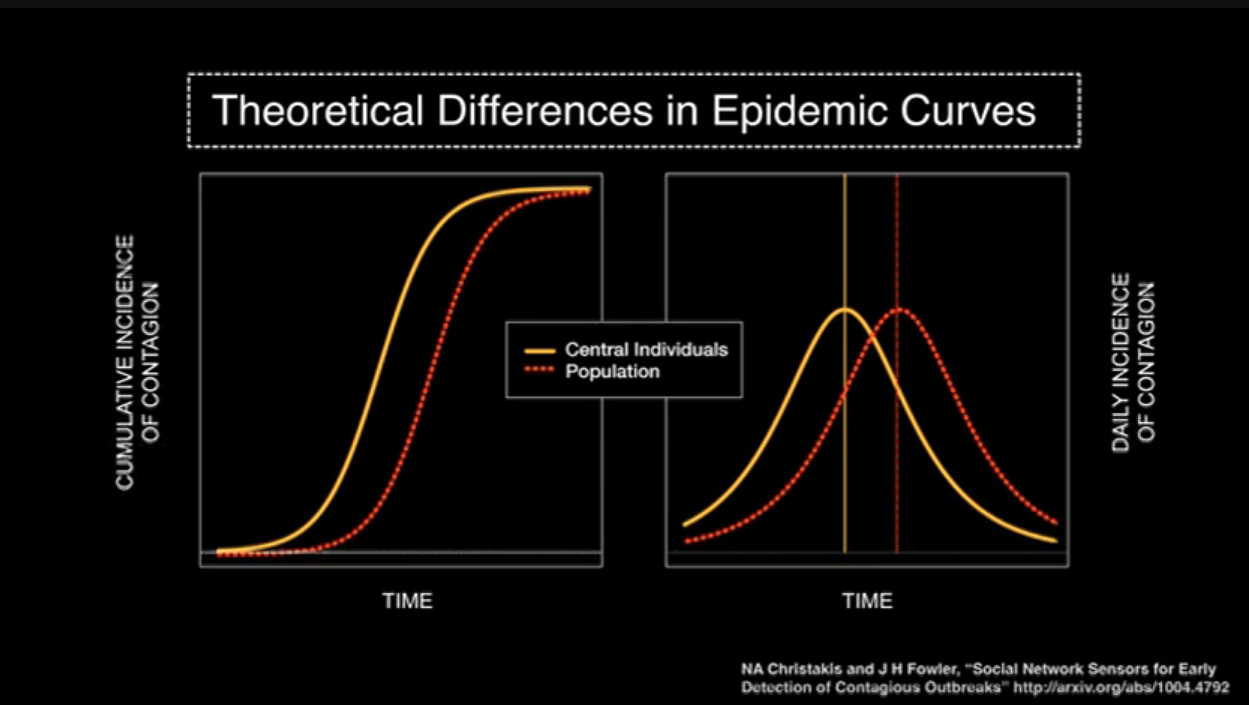

As you probably know, the classic way of thinking about this is the diffusion-of-innovation, or the adoption curve. So here on the Y-axis, we have the percent of the people affected, and on the X-axis, we have time. And at the very beginning, not too many people are affected, and you get this classic sigmoidal, or S-shaped, curve. And the reason for this shape is that at the very beginning, let's say one or two people are infected, or affected by the thing and then they affect, or infect, two people, who in turn affect four, eight, 16 and so forth, and you get the epidemic growth phase of the curve. And eventually, you saturate the population. There are fewer and fewer people who are still available that you might infect, and then you get the plateau of the curve, and you get this classic sigmoidal curve. And this holds for germs, ideas, product adoption, behaviors, and the like.

But things don't just diffuse in human populations at random. They actually diffuse through networks. Because we live our lives in networks, and these networks have a particular kind of a structure.

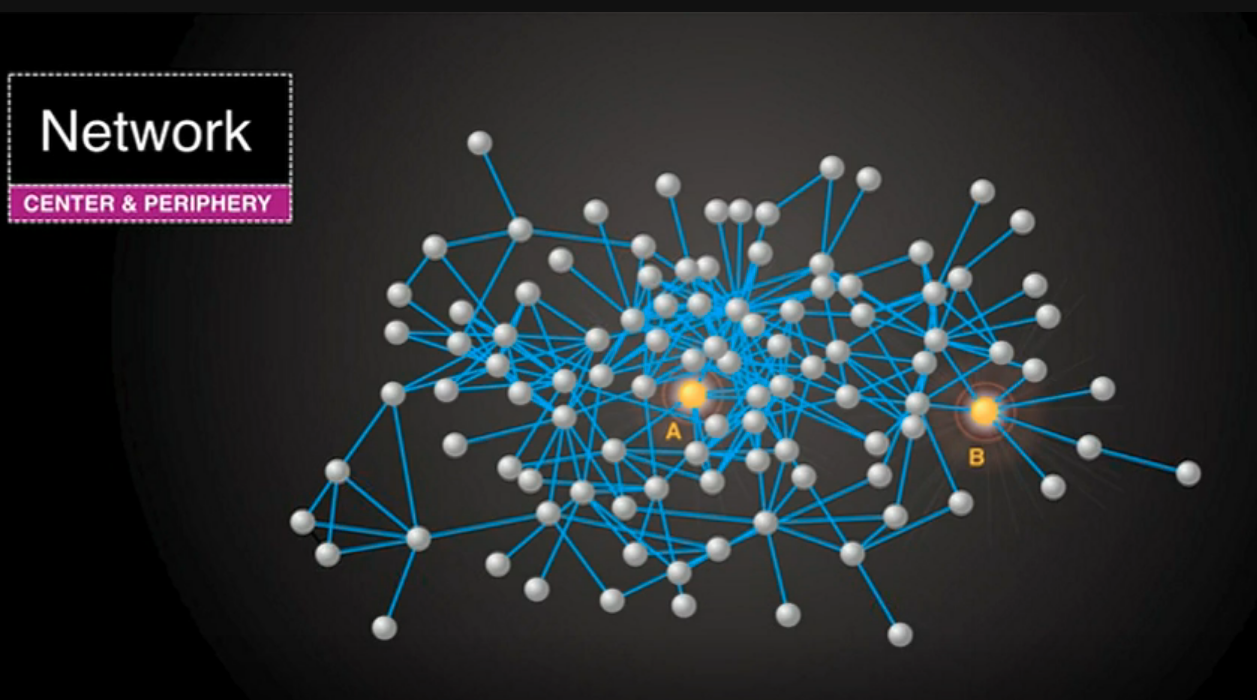

Now if you look at a network like this - this is 105 people. The dots are the people, and the lines represent friendship relationships. You might see that people occupy different locations within the network. And there are different kinds of relationships between the people. You could have friendship relationships, sibling relationships, spousal relationships, co-worker relationships, neighbor relationships and the like. And different sorts of things spread across different sorts of ties. For instance, sexually transmitted diseases will spread across sexual ties. Or, for instance, people's smoking behavior might be influenced by their friends. Or their altruistic or their charitable giving behavior might be influenced by their coworkers, or by their neighbors.

But not all positions in the network are the same.

If you look at this, you might immediately grasp that different people have different numbers of connections. Some people have one connection, some have two, some have six, some have 10 connections. This is called the "degree" of a node, or the number of connections that a node has.

But in addition, there's something else.

If you look at nodes A and B, they both have six connections. But if you can see this image [of the network] from a bird's eye view, you can appreciate that there's something very different about nodes A and B.

So, let me ask you this -- who would you rather be if a deadly germ was spreading through the network, A or B? B, it's obvious. B is located on the edge of the network. Now, who would you rather be if a juicy piece of gossip were spreading through the network? A. A is going to be more likely to get the thing that's spreading and to get it sooner by virtue of their structural location within the network. A, in fact, is more central, and this can be formalised mathematically.

So, if we want to track something that was spreading through a network, what we ideally would like to do is to set up sensors on the central individuals within the network, including node A, monitor those people that are right there in the middle of the network, and somehow get an early detection of whatever it is that is spreading through the network.

If you saw them contract a germ or a piece of information, you would know that, soon enough, everybody was about to contract this germ or this piece of information. If you could do that, what you would see is something like this. On the left-hand panel, again, we have the S-shaped curve of adoption. In the dotted red line, we show what the adoption would be in the random people, and in the left-hand line, shifted to the left, we show what the adoption would be in the central individuals within the network. On the Y-axis is the cumulative instances of contagion, and on the X-axis is the time. And on the right-hand side, we show the same data, but here with daily incidence. But shifted to the left is what's occurring in the central individuals. And this difference in time between the two is the early detection, the early warning we can get, about an impending epidemic in the human population.

The problem, however, is that mapping human social networks is not always possible. It can be expensive, not feasible, unethical, or, frankly, just not possible to do such a thing.

So, how can we figure out who the central people are in a network without actually mapping the network?

What we came up with was an idea to exploit an old fact about social networks, which goes like this: Do you know that your friends have more friends than you do? This is known as the friendship paradox. Imagine a very popular person in the social network -- like a party host who has hundreds of friends -- and a misanthrope who has just one friend, and you pick someone at random from the population; they were much more likely to know the party host. And if they nominate the party host as their friend, that party host has a hundred friends, therefore, has more friends than they do. And this, in essence, is what's known as the friendship paradox. The friends of randomly chosen people have higher degree, and are more central than the random people themselves.

And you can get an intuitive appreciation for this if you imagine just the people at the perimeter of the network. If you pick this person, the only friend they have to nominate is this person who, by construction, must have at least two and typically more friends. And that happens at every peripheral node. In fact, it happens throughout the network you move in -- when a random person nominates a friend of theirs, you move closer to the center of the network. So, we thought we would exploit this idea in order to study whether we could predict phenomena within networks. Because now, with this idea we can take a random sample of people, have them nominate their friends, those friends would be more central, and we could do this without having to map the network.

And we tested this idea with an outbreak of H1N1 flu at Harvard College in the fall and winter of 2009:

We took 1,300 randomly selected undergraduates, we had them nominate their friends, and we followed both the random students and their friends daily in time to see whether or not they had the flu epidemic. And we did this passively by looking at whether or not they'd gone to university health services. We also had them [actively] email us a couple of times a week.

Exactly what we predicted happened.

The random group is in the red line. The epidemic in the friends group has shifted to the left, over here. And the difference in the two is 16 days. By monitoring the friends group, we could get 16 days advance warning of an impending epidemic in this human population.

I should say that how far advanced a notice one might get about something depends on a host of factors. It could depend on the nature of the pathogen -- different pathogens, using this technique, you'd get different warning -- or other phenomena that are spreading, or frankly, on the structure of the human network. In our case, although it wasn't necessary, we could also actually map the network of the students.

As I've been suggesting, this method is not restricted to germs, but actually to anything that spreads in populations. Information spreads in populations, norms can spread in populations, behaviors can spread in populations. And by behaviors, I can mean things like criminal behavior, or voting behavior, or health care behavior, like smoking, or vaccination, or product adoption, or other kinds of behaviors that relate to interpersonal influence. If I'm likely to do something that affects others around me, this technique can get early warning or early detection about the adoption within the population. The key thing is that for it to work, there has to be interpersonal influence. It cannot be because of some broadcast mechanism affecting everyone uniformly.

Similar ideas can be used, for instance, to target distribution of things like bed nets in the developing world. If we could understand the structure of networks in villages, we could target to whom to give the interventions to foster these kinds of spreads. Or, frankly, for advertising with all kinds of products. If we could understand how to target, it could affect the efficiency of what we're trying to achieve. And in fact, we can use data from all kinds of sources nowadays [to do this].

This is a map of eight million phone users in a European country. Every dot is a person, and every line represents a volume of calls between the people. And we can use such data, that's being passively obtained, to map these whole countries and understand who is located where within the network. Without actually having to query them at all, we can get this kind of a structural insight. Other sources of information are available about such features, from email interactions, online interactions, online social networks and so forth. In fact, we are in the era of what I would call "massive-passive" data collection efforts. They're all kinds of ways we can use massively collected data to create sensor networks to follow the population, understand what's happening in the population, and intervene in the population for the better. Because these new technologies tell us not just who is talking to whom, but where everyone is, and what they're thinking based on what they're uploading on the Internet, and what they're buying based on their purchases. All this administrative data can be pulled together and processed to understand human behavior in a way we never could before.

There are three ways that these massive-passive data can be used.

Fully passive, where we don't actually intervene in the population in any way.

Quasi-active, like the flu example, where we get some people to nominate their friends and then passively monitor their friends -- do they have the flu, or not? -- and then get warning.

Fully active where people might globally participate in wikis, or photographing, or monitoring elections, and upload information in a way that allows us to pool information in order to understand social processes and social phenomena.

In fact, the availability of these data, heralds a kind of new era of what I and others would like to call "computational social science." Now we have access to these kinds of data that allow us to understand social processes and social phenomena in an entirely new way that was never before possible. With this science, we can understand how exactly the whole comes to be greater than the sum of its parts. And actually, we can use these insights to improve society and improve human well-being.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, MPH, is an internist and social scientist who conducts research on social factors that affect health, health care, and longevity. He is Professor of Medical Sociology in the Department of Health Care Policy at Harvard Medical School; Professor of Medicine in the Department of Medicine at Harvard Medical School; Professor of Sociology in the Department of Sociology in the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences; and an Attending Physician (with an emphasis on palliative medicine) in the Department of Medicine at the Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

This is an extract from a 2010 talk delivered by Nicholas Christakis entitled "How social networks predict epidemics" delivered at TED@Cannes, published under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Related Skill

Book a class related to this article:

The 5 types of influencers you should work with

For the past two years Treeshake has helped Water Advocate Mina Guli get her message out online. For the launch of her latest campaign, Running Dry, we gained the support of influential leaders on social media to reach over 18m people online in a day . Here's how we did it.

Influencer marketing can be one of the most powerful ways to get people interested in an issue. Simply put, it's about getting people of influence to speak about your brand. But it's more than a tactic - considerations include making sure your campaign is actually worth talking about, and then making sure you involve the right influencers.

That's where our 5 types of influencers comes in. Most of the discussion about influencers is about a) number of followers, b) levels of engagement, and c) topic relevance. However, in practice we found that there's not ONE kind of influencer that's right for a campaign - there are FIVE. Namely, Pioneers, Amplifiers, Authorities, Participators, and Scalers.

We've shied away from the typical industry language of "brand influencers", "micro-influencers", "influencers", and "celebs" because those specifically refer to number of followers rather than the role the influencer plays in a campaign.

To illustrate how we work with these influencers, and explain the categories we'll use a live campaign example...

On World Water Day , 24th March 2018, Water Advocate Mina Guli announced that she will be running 100 marathons in 100 days for 1 reason: Water. We were tasked with getting this announcement out on social media, and ensuring that her message of water conservation came through as clearly as the message of ultra endurance inspiration.

Using our Social Media Fireworks approach, we reached over 18 million people. But as you'll see in this post, it is not only that we reached LOTS of people, it is that we were joined by the RIGHT people. Some of the most influential and credible players in the space of water conservation, sport, and business supported the launch on World Water Day by mentioning Mina's campaign directly as well as the #everydropcounts hashtag.

Here are the 5 types of influencers we message and try to involve when we do a Social Media Firework:

Pioneers

The first type of influencer we’re looking at are the Pioneers -- the cool people, the front-runners. Pioneers are plugged into the scene, they're passionate about the issues.

The idea is to let these people in on the campaign as early as possible. You may even get some good ideas from your Pioneers that will improve your message.

Ok folks - this is, as ever, another impressive effort by the amazing @minaguli . I have rarely met someone more committed to water. Go Mina!! #everydropcounts https://t.co/kTMFY8ia3I

— Giulio Boccaletti (@G_Boccaletti) March 22, 2018

By 2030 humanity will be short of water by 40%. @minaguli is running 100 marathons in 100 days to raise awareness.

— Aejaz Khan (@dotkhan) March 25, 2018

In relation to the RunningDry campaign, the Pioneer Influencers we reached out to were fellow water activists and users whose feeds consisted largely of water-related content. For RunningDry, we were lucky enough to be building on the #Run4Water campaign, where we spent months ensuring Mina was following the key Pioneers in the water crisis conversation, and often getting reciprocal follows as a result. This allowed the pioneer outreach for the RunningDry launch to be carried out a lot more easily, because we could simply look through Mina’s followers for the pioneer influencers, reach out to them via DM and often have their support based on this already existing relationship.

Amplifiers

The next type of influencer to consider is the Amplifier -- they are are interested in your topic, and have a high number of engaged followers. Generally called "Influencers" they often drive the highest volume of engagement and reach in a campaign. Generally speaking their following is in the range of 100k - 1m but just as important as their large reach is their clout as conversation leaders online (you can tell by their engagement rates generally).

The amazing @minaguli is an inspiration! @YGLvoices @CityofCT #EveryDropCounts 💦 https://t.co/Ej0DjKVGgW

— Lindiwe Mazibuko (@LindiMazibuko) March 22, 2018

"If water is life, surely water scarcity — which is going to affect all of us — should be on the front page." — @minaguli on why she started @Thirst4Water 💧 #WorldWaterDay pic.twitter.com/NMEfZjvEiz

— AM to DM by BuzzFeed News (@AM2DM) March 22, 2018

Authorities

Authorities bring an added level of trust and credibility to a campaign. We're talking about institutions like universities, leading non-profits in the space, academics, and experts on the topic.

Wow, stay hydrated. Go Mina!

— Peter Gleick (@PeterGleick) March 22, 2018

Good luck! Stay hydrated. Get in touch when you are done. https://t.co/9hInKl4IL1

— Seth M. Siegel (@SethMSiegel) March 24, 2018

For Running Dry our Authority outreach included accounts like the verified World Resources, to individual gatekeepers such as Seth Siegel, author of Let There Be Water. Their participation showed people that Mina is a trusted and credible campaigner in the space of water conservation.

Participators

Participators comprise the largest proportion of your followers. They are the people who choose to follow you simply because they like your content or what you're talking about. On aggregate, participators can be the most influential of everyone in your campaign. To gain the support of Participators you need to maintain a consistently high level of relevance and entertainment value. It also really helps to activate their involvement using other channels, such as email newsletters or calls for involvement on TV and radio interviews. And of course, acknowledge and thank people for getting involved and supporting - like posts, comment back, share.

Thanks for the moderate "impractical", Stephen. Generally, it's met with "mad" "impossible" ... but this is my 100%, all in 💧🌎

— Mina Guli (@minaguli) March 22, 2018

So right, Jenine, that's why I'm giving my all. 100% commitment: 100 marathons 100 days because #EveryDropCounts now

— Mina Guli (@minaguli) March 22, 2018

Scalers

The Scalers are Celebs with mega-reach because of their huge follower counts. Even a simple share or retweet from them can be a major boost. Having their support helps you take your campaign into the mainstream.

Relatively light engagement from celebrities including Maria Sharapova, Karen Davila, and Don Riddell brought the campaign into millions of people's timelines. These were unpaid endorsements based on the strength of Mina's story and the importance of her message.

Incredible. 👊🏻🙌🏻 https://t.co/VYQ7omHYIU

— Maria Sharapova (@MariaSharapova) March 22, 2018

It’s #WorldWaterDay! Please check out my friend @minaguli’s page! She has run the world - giving attention to the water crisis! 💦💦 https://t.co/R2kRRF4XpE

— Karen Davila (@iamkarendavila) March 22, 2018

Online and Offline Influence

Lastly, Mainstream Media and Social Media are a great compliment. It's always encouraging for news organisations to see that an issue is gaining traction online. So thanks to supporters like CNN's Don Riddel and Al Arabiya's Talal Al Haj, Mina's story was carried off social media and into millions of homes around the world by broadcast television.

Diplomatic Avenue - @MinaGuli talks to Al Arabiya's @TalalAlhaj on why she is running 100 marathons in 100 days to raise awareness regarding #watercrisis https://t.co/ccMqdoYt08 pic.twitter.com/bGKoNkD77D

— Al Arabiya English (@AlArabiya_Eng) March 31, 2018

Highlighting the perilous state of our global water supply, the amazing @minaguli is planning 100 Marathons in 100 Days: https://t.co/RN1RGc5wnP

— Don Riddell (@donriddellCNN) March 26, 2018

Dave Duarte, founder of Treeshake, is passionate about community engagement as a driver of value. As social marketer, speaker, facilitator and advisor, his warm and engaging style makes the future easy to engage with. Dave brings over a decade of facilitation experience to his work at Treeshake. He has founded several businesses, and served in leadership positions in media, academia, and non-profits.